![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

‘In GM crops, I can find no serious evidence of health risks’

Tony Blair, speaking to The Royal Society, May 20021

‘Political language is designed to make lies sound truthful’

George Orwell2

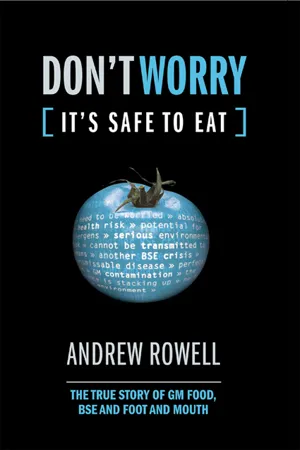

‘Don't worry – it's safe to eat’ is a familiar phrase uttered by both politicians and scientists to reassure consumers that the food they eat on a daily basis is safe. It was issued like a mantra throughout the BSE crisis and we are now being told the same about genetically modified (GM) foods.

As vast swathes of the developing world struggle to eat enough food, many in the developed world continue to be worried by what they eat, so much so that the food safety issue remains a hot political topic. Over two-thirds of people within the European Union (EU) are worried about food safety.3 A recent survey in the UK found that two-thirds of UK consumers describe themselves as ‘very’ or ‘quite’ concerned about food safety.

The Food Standards Agency (FSA), the new body responsible for food safety in the UK, who commissioned this latest research, is at pains to point out that, although this number is high, it has dropped slightly over the last two years. So have the number of people who are concerned about BSE (bovine spongiform encephalopathy) – although just under half (some 45 per cent) remained worried about it in the UK.4

The FSA will use apparent declining consumer concern to justify relaxing the rules that have been put in place to protect the consumer against BSE. In February 2003, Sir John Krebs, the Chairman of the FSA, indicated that this would happen, a move considered premature by those who represent the families of the 122 people who have died from the human equivalent of the disease (known as variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease or vCJD). As we shall see in Chapter 2, the evidence and the science are not as clear-cut as the government might like us to believe.

A re-occurring phenomenon during the BSE crisis was that critical scientists were marginalized and vilified, and Chapter 3 looks at what happened to some of the prominent scientists and government critics during the BSE crisis.

But BSE is supposedly all behind us now. The British government reassures consumers that the torrid lessons of the BSE saga have forged a new political landscape; one where openness and the consumer reign supreme. Alan Milburn, British Secretary of State for Health, argues that in response to BSE the government has ‘sought to put the consumer at the heart of the decision-making on food safety issues and we have established the independent Food Standards Agency. We have opened up our Scientific Advisory Committees and put scientific advice to government in the public domain, encouraging a culture of openness.’5

In essence, this book examines that one paragraph, whether the lessons have been learnt, and whether there is a culture of openness surrounding science, food and farming. It is also especially relevant to the debate on genetic engineering. Fundamentally it is whether consumers’ interests are really being put first by the government.

Indeed, although the introduction of the FSA has to be seen as a good step forward, its record since its inception does not promote confidence in the protection of the consumer. The role of its Chairman, Sir John Krebs, in promoting GM food and undermining organic produce has been questioned by consumer organizations and is explored in Chapter 10.

It is also the reason why in Chapter 4 this book examines what happened during the foot and mouth crisis in the UK. Whilst you could argue that this is not directly a food safety issue, the response to the crisis shows that, contrary to what the Labour government would like us to believe, nothing much has changed since the dark days of the BSE crisis, despite a change of government. Once again critical voices were marginalized.

The issues of BSE and foot and mouth disease both leave some very difficult questions unanswered, but one major lingering doubt is whether corporate interests or consumer interests will win the debate over food safety. Nowhere will that be more of an issue than with the topic of GM foods.

We stand on the verge of what is called the ‘biotech century’, in which genetic engineering will alter our world in quite profound ways, from GM foods to ‘bio-pharming’ (crops that produce vaccines and medicines) to cloning. We are promised that this genetic revolution could end world hunger and eradicate the diseases that continue to plague us.

Whilst politicians and the biotech industry promote GM, consumers in Europe, at least, are hostile to it. Surveys show that 94 per cent of Europeans want the right to choose whether to eat GM food and a staggering 71 per cent do not want to eat it at all.6 In the UK at the beginning of 2003, consumers were meant to be at the centre of the ‘public debate’ on GM that will decide whether and how commercialization of GM will happen. The majority of the public in the UK is firmly against commercialization. A survey by the Consumers’ Association in September 2002 found that 68 per cent were against the growing of GM crops for commercial purposes and some 57 per cent had concerns about GM foods.7

The unpalatable truth for governments across Europe is that people have real worries over GMOs (genetically modified organisms), and that these cannot be as easily dismissed as the pro-GM lobby would like. ‘Consumer concerns about GM foods have been all too easily dismissed as emotional, anti-science and anti-progress’, said the Consumers’ Association.8

People worry about corporate control of our food supply. Over 60 per cent of the international food chain is controlled by just ten companies that are involved in seed, fertilizers, pesticides, processing and shipments. Cargill and Archer Daniel Midland control 80 per cent of the world's grain, and Syngenta, DuPont, Monsanto and Aventis account for two-thirds of the pesticide market. Just four companies control the supply of corn, wheat, rice and other commodities.9

People worry about the health effects of GM food. In part to allay these fears, in May 2002 Britain's Prime Minister, Tony Blair, told the scientific establishment in the UK, The Royal Society, there was no health risk from GM foods. However, one scientist who believes that he has uncovered critical evidence that GM crops cause harm is Dr Arpad Pusztai, who spoke out on World in Action in 1998. The full story of what happened to him is told in Chapter 5. Pusztai was castigated by The Royal Society, who still hound him to this day, and their role is critically analysed in Chapter 6.

In marked contrast to The Royal Society in the UK, The Royal Society of Canada's Panel of Experts into Biotechnology has identified ‘serious risks to human health such as the potential for allergens’.10 The risks associated with GM and a number of flaws in the US and UK regulatory systems are examined in Chapter 7.

But Pusztai is not alone in being vilified for raising concerns about GM. One burning issue surrounding GM is contamination of non-GM and organic food. These fears were fuelled by research published in Nature that showed that GM had contaminated native maize in November 2001. The scientists who published the research, Ignacio Chapela and David Quist, have also been attacked. Their story is told in Chapter 8.

Part of the reason that Chapela believes he was vilified is that he had opposed a large corporate tie-up between the university where he worked and a huge transnational biotech company. Increasingly, this is becoming the norm, and the issue of the corporatization of science is considered in Chapter 9.

Finally, in Chapter 11, the book looks at radical ways to reform agriculture and science. As we face decisions on GM commercialization our judgement is guided not only by looking to the future, but also to the past. This time we must learn from our mistakes, rather than repeat them.

Over the last 50 years the preoccupation has been to provide cheap food. Whilst this might have made sense decades ago, the ravages of foot and mouth disease and BSE have meant that the cheap food mentality is no longer plausible in the long-term. The most persuasive argument for change is that the current system is neither safe, nor economically or environmentally sustainable. This mentality has produced an inefficient, intensive system in which the world's richest 16 countries subsidize their agricultural sectors to the tune of US$362 billion a year, whilst 2 million children in the developing world die each year because of contaminated water and food supplies.11

We know that in the UK the agriculture industry is in a mess. The National Farmers’ Union (NFU) talks about a ‘decade horribilis’, in which BSE, foot and mouth disease, exchange rates and commodity prices have all created problems for the UK farmer.12 Since 1997, farm incomes have fallen by 75 per cent and the average farm income at the time of writing is now less than £10,000. At least one farmer or farm worker commits suicide each week.13 The average age of a UK farmer is 58, with little indication of an influx from the younger generation.14 Demand for their products is also declining. Over the last two years alone some 7.5 million British consumers have reduced their consumption of meat.15

Moreover, cheap food is actually a myth. Consider the external or hidden costs. It costs nearly £120 million to remove pesticides from drinking water every year. Atmospheric pollution from UK agriculture causes indirect costs of some £1 billion, including those brought about by climate change.16 ‘We pay three times over’, says Professor Jules Pretty from the University of Essex. ‘Once at the till, then again through tax for EU subsidies and then again through hidden subsidies.’ The hidden costs of industrial agriculture – damage to soil structure, pollution and environmental damage – Pretty believes, is in the region of £2.34 billion a year.17 Our biodiversity is slowly being eroded. Two-thirds of England's hedgerows were lost between the 1950s and 1990s18 and nearly two-thirds of the population of skylarks has been wiped out in the last 30 years.19

Furthermore, our cheap food policy has not produced healthy people. We are eating too much of the wrong food and not enough of the right food. In the USA, where over 60 per cent of people are already overweight or obese, 90 per cent of money spent on food is spent on processed food. French fries are now the most widely sold food item in the USA and each person already drinks over a gallon of soda a week, while some teenage boys drink five or more cans per day.20

In the UK, diets are not much better and are getting worse. People are eating more and more processed and packaged food, and less and less fresh food. The demand for frozen convenience meat products has grown by 127 per cent since 1978.21 People are literally losing the ability to cook. At least three-quarters of UK men and woman are expected to be overweight within 10 to 15 years, and obesity could become as important a health issue as smoking.22

The diet of children in the UK is similarly appalling, with over £8 million spent each week on junk food. On average, children in the UK eat less than half the recommended amount of fruit and vegetables; and between 75 and 93 per cent eat more saturated fat, sugar and salt than is recommended for adults.23 Of the food adverts shown during children's TV, 99 per cent are for products that are high in fat, sugar or salt.24 UK childhood obesity rates are reaching epidemic proportions, with one in five nine-year olds overweight and one in ten obese – rates that have doubled in the last ten years.25

This Western cheap food policy has not produced appetizing food. The current supermarket status quo is summarized by the food writer Joanna Blythmann as ‘permanent global summer time’ (PGST), a ‘curiously uniform, nature-defying new order’ where tasteless, unvarying imports take over from fresh, locally grown produce.26 Similarly, this policy has not produced safe food. In the USA, 76 million people suffer from food-borne di...