From the ‘glorious twenties’…

At the beginning of the 1970s, the Harvard Business School’s Research Division started some field research in order to investigate key features of the largest European corporations.1 The analysis focused on four European countries (France, Italy, United Kingdom and West Germany), which during the two decades before had been involved in a process of intense economic growth and ‘social modernisation’. Big firms dominated the capital-intensive industries of the second industrial revolution in these countries, while Europe-based multinationals were more and more successful challengers in international markets (Franko, 1976).

The main research question for the HBS scholars was, thus, to understand to which extend this economic modernisation corresponds with an updating process of organisational structures in order to catch up the benchmark represented by the (at that time) globally dominant large corporations from the United States. The evidence underpinning the research was constituted by data collected on the top 100 companies in each country by turnover in the period 1950–70, examined according to the strategies adopted (single, dominant, related and not related activities), and organisational structure (‘U-form’, ‘M-form’ and – in order to take into account what was a distinctive European feature – ‘functional holding’ and ‘holding’, characterised by an higher degree of subsidiaries’ autonomy) (Rumelt, 1974). A shared belief – and one of the research’s main research questions – was the inevitable convergence between Europe and the United States, both in terms of strategy and organisation. This belief was largely – if not fully - confirmed by the evidence emerging from the country studies.

In 1950 only one-quarter of the top 100 corporations in the United Kingdom had diversified their activities, but by 1960 a deep change had taken place. Diversification and the multi-business organisational forms were spreading rapidly; by 1970, multi-business forms had been adopted by more than the 70% of the largest companies. Similar patterns were evident in West Germany and even in France and Italy – the most backward among the four countries analysed – in which in 1970 48 of the top 100 firms had adopted multidivisional structures. This process of convergence had many determinants, among which the process of Americanisation and transformation of the European big business following World War II (Schroeter, 2005). Important drivers of these dynamics were the European Recovery Programme (Marshall Plan), which was accompanied by strong pressures by the Americans in order to speed up the process of liberalisation of the European economies after the interwar autarchic closures. Due to this programme, the European countries came in close contact with the American organisation techniques. Thanks to the ‘US Technical Assistance and Productivity Mission’, for instance, American managers and businessmen travelled to Europe bringing information about organisation and modern management practices, while Europeans crossed the Atlantic in order to learn about the same topics. During the two decades following WWII, the ‘golden’ phase characterised by a progressive increase in the size and dynamism of domestic markets, the largest companies pursued consolidation strategies, particularly evident in capital and technology intensive industries. A telling signal of the transformation of the nature and structure of European large corporations was, for instance, the steady growth in business consulting activities (Kipping & Bjarnar, 1998; Kipping & Engwall, 2002). Consultants – typically US-based companies opening branches in post-war Europe – acted as powerful drivers in the diffusion of strategic and organisational models designed on the other side of the Atlantic and adapted these models to the needs of fast-growing European ‘national champions’.

The intense growth in demand and consumption rates was also incentivised by several trade agreements, which culminated in the creation of the European Common Market (ECM) in 1957. This treaty provided European firms with the necessary basis for mass production and distribution, for the first time in modern times. During the 1960s the large companies of the member states engaged in an increasingly intense activity in the European market, increasing both exports and international investments. At the same time, American FDI intensified jointly with a flow of new technologies, new products, and (at least for Europe) new organisational forms and marketing techniques. This process resulted in a major challenge to European large corporations, both private and state owned, which were increasingly called on to adapt their structural features to the new market situation (Servan-Schreiber, 1968).

As the ‘Harvardians’ soon discovered, however, the outcome was far from being a ‘perfect convergence’ towards the US model of the large, managerial corporation characterised by a high degree of diversification, by divisional structures and by dispersed ownership. On the contrary, in Europe concentrated ownership structures apparently persisted everywhere, together with organisational models emphasising centralised control more than delegation, as the U-form and, above all, the holding state and family ownership, together with a strong role played by financial institutions, led to a high degree of ownership concentration. The influence of large shareholders was further enforced through the widespread use of control-enhancing mechanisms, such as pyramid schemes, shareholder agreements, cross-shareholdings and dual-class shares, all enduring features of the (continental) European corporate governance model (Barca & Becht, 2003; Morck, 2007). Additionally, and the long process of growth notwithstanding, families and individuals could easily manage the enterprises they controlled, because firms were generally smaller than their American counterparts. For instance, at the beginning of the 1970s, turnover of the British largest firm was less than half of that of the largest in the United States (Channon, 1973); in West Germany and Italy this proportion was one-fifth, and in France only one-tenth (Pavan, 1973; Dyas & Thanheiser, 1976).

… to the nineties

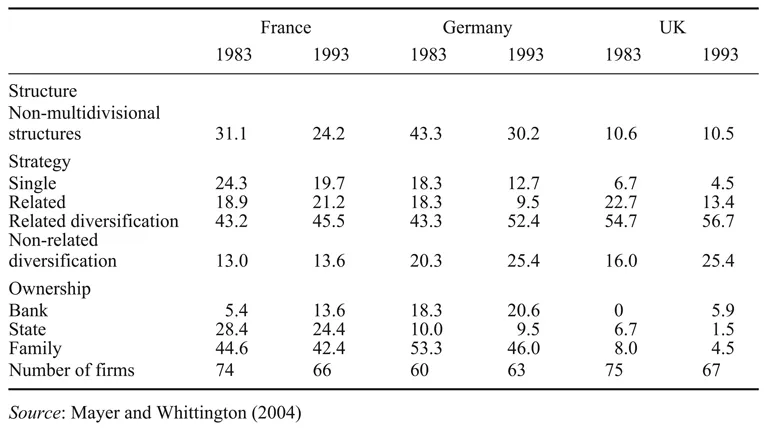

Despite cultural and structural resistances, however, the multidivisional enterprise progressively diffused in Europe. The steadiness of the process has clearly been confirmed by a study by Richard Whittington and Michael Mayer concerning the 100 largest British, French and German corporations between 1985 and 1995 at the end of the millennium (Whittington & Mayer, 2000), which stresses the convergence process – at least in the three main economies of Europe – towards the adoption of multidivisional structures and strategies of (related) diversification (see Table 1.1). The general slowdown in the European process of economic growth during the 1970s and early 1980s notwithstanding, the process of convergence towards the American organisational model went on – even if this were in some ‘European’ way.

Another relevant finding of Wittington and Mayer’s contribution has been the persistence of concentrated ownership structures, which were only partially challenged by the intense privatisation process in the UK and France in the second half of the 1980s,

Table 1.1 Percentage of companies in their structure, strategy and ownership.

and elsewhere at the beginning of the 1990s. The state still maintained an important role in many industries, acting as either an owner or controller of corporate assets, often through control-enhancing mechanisms as ‘golden shares’ and other provisions (Bortolotti & Faccio, 2009), while families and banks strengthened their role as blockholders of privatised companies in many countries.