![]()

Introduction: Analysing Differentiation and Convergence in Euro-Mediterranean Relations

ESTHER BARBÉ and ANNA HERRANZ-SURRALLÉS

The 2011 episodes of regime change in the Arab world obliged the EU once more to reassess its Mediterranean policy. This time, the need for a novel approach came less from the EU’s disillusionment with the pace of political and economic reforms in the southern Mediterranean countries, and more from its sense of failure and embarrassment for not having appropriately gauged and contributed to the winds of democratic change in this area. It is in this sense that the Commissioner for Enlargement and European Neighbourhood Policy bluntly affirmed, after the ousting of the Tunisian and Egyptian presidents, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali and Hosni Mubarak, in early 2011, that ‘Europe was not vocal enough in defending human rights and local democratic forces in the region. Too many of us fell prey to the assumption that authoritarian regimes were a guarantee of stability in the region’ (Füle 2011: 2). In order to redress former policy flaws and rise to the challenge of the history-making events in the Arab world, the European Commission called for a new approach to Euro-Mediterranean relations based on more differentiation, encapsulated in the motto ‘more for more’, or the promise of greater support from the EU to those countries going further and faster with reforms (European Commission, 2011a: 5).

The idea of differentiation in Euro-Mediterranean relations is certainly not new. This concept did not figure prominently in the initial design of the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership instituted in 1995, the first truly multilateral and comprehensive project to channel relations between the EU and southern Mediterranean countries. However, the obstacles, which soon plagued this ambitious region-wide endeavour, compelled the EU to look for flexibility mechanisms enabling cooperation with those partners and issue areas in which progress was possible. In this way, differentiation has been entrenched in subsequent EU initiatives for the region, most notably in the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) launched in 2004 which embraced bilateral differentiation as one of its guiding principles; and more recently in the Union for the Mediterranean (UfM), conceived as a mechanism to boost more flexible cooperation around specific and technical-oriented projects.

This trend towards greater differentiation in Euro-Mediterranean relations has not moved forward without debate. On the contrary, experts have recurrently discussed whether a less regional and holistic approach is a welcome pragmatic development or is rather a sign of fragmentation and an obstacle to more ambitious region-building projects. However, despite many insights into the advantages and disadvantages of differentiation, compared to region-wide and comprehensive approaches to Euro-Mediterranean relations, this topic has not been tackled in a structured manner in the literature. The debate regarding the pros and cons of differentiation has mostly been addressed (often only in an implicit manner) when assessing overall institutional frameworks for relations between the EU and the Southern and Eastern Mediterranean Countries (SEMC).1 Conversely, there has been less focus on taking the debate to a more concrete level and assessing the effects and implications of differentiation dynamics on cooperation in particular issue areas.

This is the task undertaken in this volume. Covering a wide and diverse range of issues – environment, civil protection, trade in goods, energy, security and defence and migration – the contributions specifically investigate the following questions: Are there significant differentiation dynamics taking place in the specific issue area considered? By whom are these triggered and for what purpose? Do differentiation mechanisms contribute to policy convergence at least in particular domains and/or with certain countries? But more importantly, does differentiation increases the chances of boosting political reform and socioeconomic development? Or what do the dynamics of differentiation and patterns of convergence imply in terms of broader region-building efforts?

The main purpose of this introductory chapter is to present the terms of the debate regarding differentiation in the context of Euro-Mediterranean relations while also defining the key guiding concepts used by the authors of this collection. With this aim in mind, the chapter begins with a brief section presenting the concepts of differentiation and policy convergence in the context of regional cooperation. The second section spells out how certain patterns of differentiation and convergence relate to different models for region building, and illustrates this point by reviewing the various initiatives promoted by the EU in the Mediterranean since the inception of the EMP. Finally, the chapter points to some interesting lines of discussion opened up by the contributions to this volume, and then closes with some final remarks on the implications of the findings in relation to the EU’s new approach to the Mediterranean region after the political shakeup of 2011.

Conceptual Underpinning: Researching Regional Cooperation through Differentiation and Convergence

Since the mid-1900s the terms ‘Mediterranean’ and even ‘Euro-Mediterranean’ have consolidated into meaningful political and analytical categories (Gillespie and Martín, 2006: 151; Pace, 2006: 1–4; Panebianco, 2001: 179–84). However, the definition of the Euro-Mediterranean space is contested. Some refer to it as an instance of open regionalism (Joffé, 2001), or even a security community in the making (Adler and Crawford, 2006), whereas others declare that the Mediterranean does not constitute a region in any geographic or social sense (Horden and Purcell, 2000). Less contended is the fact that since the early 1990s the EU and the SEMC have been consistently involved in processes aimed at encouraging greater regional interaction. It is from this point of view that the term region building is used here, as an umbrella concept to describe purposeful activities intended to encourage sustained and gradually more homogeneous densification of the web of relations in the Euro-Mediterranean area.

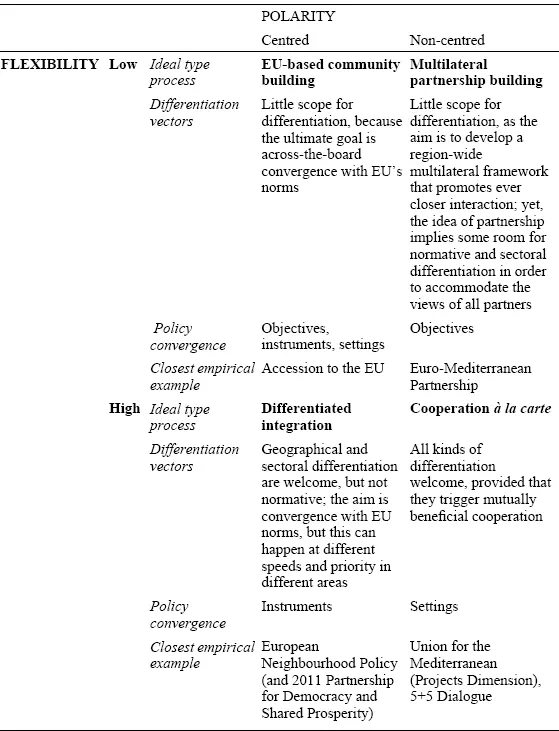

For the purpose of researching the dynamics of differentiation and policy convergence emerging in the Euro-Mediterranean, we have conceptualized four basic region-building models: (i) EU-based community building, (ii) multilateral partnership building, (iii) differentiated integration, and (iv) à la carte cooperation. As illustrated in Table 1.1, these four models are distinguished on the basis of two criteria: polarity, indicating whether relations are EU centred or not, and the degree of flexibility envisaged in the cooperation scheme. We describe, in more detail, the logic of these models in the next section using empirical examples and debates regarding the evolution of Euro-Mediterranean relations. Prior to that, the remainder of this section presents our definitions of the concepts of differentiation and policy convergence.

Differentiation

If region building is about attaining more intense and homogeneous relations in a given area, then it might seem difficult to reconcile differentiation with such a notion. It would, however, be unrealistic to assume that a region can be created and sustained along completely uniform lines. The EU integration process itself has long been characterized by several differentiation and flexibility mechanisms (cf. Stubb, 1996). Therefore, the debate is not whether policy differentiation is compatible with region building, but what type of differentiation is allowed or promoted in different region-building models (see the next section). Specifically, in the context of Euro-Mediterranean relations, we distinguish between three main differentiation vectors: geographical, sectoral and normative, as described in what follows.

Geographical differentiation is perhaps the most typical form of differentiation, which for Euro-Mediterranean relations basically means that relations between the EU and the SEMC are conducted on a bilateral basis, evolving at their own pace and in their own direction. Certainly, bilateral relations are a component of every type of initiative, even in the framework of the EMP, which included a bilateral element through the association agreements. However, the key is whether these bilateral relations are purposefully encouraged to evolve in a significantly different manner. Geographical differentiation can also occur in a sub-regional format, such as for cooperation in the framework of the 5 + 5 dialogue in the western Mediterranean.

Table 1.1 Region-building models

Source: own elaboration

Sectoral differentiation refers here to the differentiated treatment (practical exclusion or underdevelopment) of a certain aspect originally envisaged as part of the same policy package or considered necessary for regional integration. On a very general level, examples of sectoral differentiation can be found in many domains of Euro-Mediterranean cooperation. In the economic domain, for instance, trade liberalization has advanced unevenly across different sub-sectors, focusing on industrial goods and largely excluding agriculture and services. At the same time, relations have almost exclusively focused on tariff reduction, whereas non-tariff barriers have remained high so far. Another general example of sectoral differentiation can be observed in the domain of foreign and security policy, where cooperation has tended to focus on issues of an internal–external nature, such as terrorism, organized crime and civil protection, rather than on issues related to military and defence cooperation.

Normative differentiation refers to differences in the norms and rules that sustain and guide cooperation between partners on a specific issue. It has been widely assumed that the aim of most EU policies towards neighbouring countries is to promote their convergence with the EU system of norms and rules. In other words, the EU is considered the sole generator of norms and the actor setting the model for the SEMC. However, we want to emphasize that relations between the EU and these countries can also be based on other normative grounds, such as norms developed by international institutions, and in other cases, there might be no directly applicable model, so the EU and the partner country/ies may develop tailor-made rules.2 Hence normative differentiation is here conceptualized to grasp whether cooperation between the EU and the SEMC is designed to converge towards a single model (that of the EU) or, conversely, if there is scope for a more varied choice.

Policy Convergence

We assume that all region-building processes aspire to trigger some degree of policy convergence. We define policy convergence as ‘any increase in the similarity between one or more characteristics of a certain policy (e.g. policy objectives, policy instruments, policy settings) across a given set of political jurisdictions (supranational institutions, states, regions, local authorities) over a given period of time’ (Knill, 2005: 768). The term policy convergence is preferred to other similar concepts such as policy transfer for various reasons. First, policy convergence seems more accurate in the particular context of Euro-Mediterranean relations because it denotes a trend rather than an outcome, and therefore is a better fit for an analysis of the interaction between actors that have no legal or political obligation to adopt external norms and rules from one another. Second, it facilitates a wider definition of the origin of pressures to introduce policy changes. In other words, policy convergence could arise from many sources, such as active promotion of a norm by an external actor, less apparent diffusion and learning processes, domestic societal demands or systemic economic or security pressures. Finally, policy convergence allows for a more flexible analysis of the directions that convergence might take. It could be argued that, given the asymmetry of EU–SEMC relations, unilateral policy transfer is the best way to characterize the dynamics of these relations. However, attention also needs to be placed on the contribution of the SEMC in shaping the different paths and degrees of convergence with the EU (Barbé et al., 2009a, b). Putting it another way, the term provides a more open way to address who converges with whom, and not only one-sided convergence.

Policy convergence is, however, a broad term that can include both output and outcome. The contributions to this volume address both dimensions, although the latter (the actual policy implementation and its practical consequences) is always more difficult to grasp and compare across cases. In terms of output, there are also several specific dimensions of policy that might experience change. Following the classical characterization by Hall (1993) from the more general to the more concrete, three basic elements can be distinguished: (i) policy objectives: the overall normative framings of a policy and standards of legitimacy of the policy foundations; (ii) policy instruments: the introduction of new institutional, financial or legal instruments within the existing policy framework; and (iii) policy settings: changes in the use of existing instruments, such as allocating more funds or political priority to one particular domain.

To conclude this section, we would like to emphasize that this focus on differentiation and policy convergence in Euro-Mediterranean relations does not preclude taking into account less state-centred components of region-building endeavours. In this sense, transnational societal bonds and other types of informal social communication and information are often seen as more important to create a sense of shared region, or even community, than elite-driven attempts at policy approximation. So, while focusing on the policy dimension, the articles in this volume also try to take into consideration relevant transgovernmental, transnational and societal processes influencing regional developments in different issue areas.

Normative Debates: Towards Flexible Region-Building or Fragmentation?

There is little doubt that the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership is the initiative that best fits the notion of region building in the Euro-Mediterranean area so far, as it was the first attempt to create a Euro-Mediterranean ‘region’ through purposeful promotion of economic, political, social and cultural interaction (Calleya, 1997). In contrast to initiatives such as the Global Mediterranean Policy and the Renovated Mediterranean Policy, launched in the early 1970s and in 1990s respectively, the EMP was conceived as a multilateral and holistic partnership. As is clear from the Barcelona Declaration, the most concrete and far-reaching area of cooperation was the economic and financial domain, but the process also provided an institutional basis for intensified multilateral dialogue on political and security issues and the promotion of social and cultural exchange. This was mainly a top-down regionbuilding project steered by political elites through intergovernmental settings, but also comprised a bottom-up component through encouragement of civil societal encounters. Therefore, this multilateral and densely institutionalized framework for cooperation reflected an idea of region building in a thick sense, that is, guided by the aim of creating conditions for the emergence of a sense of common purpose and, for most optimists within the field, even shared identities, myths and narratives. In the words of Nicolaïdis and Nicolaïdis (2006: 344): ‘the originality of the EMP process lies in its ability to bring together countries of the South and the North in a dialogue about a shared political space’.

As conceptualized in Table 1.1, the EMP largely fits the ideal model type of multilateral partnership building. Accordingly, the kind of policy convergence envisaged with the EMP was a broad one, namely convergence in objectives, rather than in concrete policy instruments and settings. Likewise, differentiation would have to be kept to a minimum, especially in geographical terms, to retain multilaterality. Yet, the Barcelona Declaration’s insistence on the ‘spirit of partnership’ and the very broad character of this document also implied that it would be possible to consider some degree of differentiation in regard to the issue areas and norms on which to base cooperation (i.e. sectoral and normative differentiation) in order to adequately reflect the interests and views of each partner.

However, practice soon cast doubt on the actual possibility of sticking to the initial EMP formulation. Two processes can be identified in this regard. On the one hand, despite the celebrated ‘spirit of partnership’, the project very soon showed a tendency toward increasing EU-centredness. The European Commission took a lead role in setting the priorities and monitoring technical assistance. In this context, reasonable doubts emerged regarding whether the EMP was less of a partnership and more of a hierarchical setup to promote convergence with EU norms and rules. On the other hand, the initial region-wide vision was difficult to carry through, therefore demanded more flexible mechanisms for cooperation. The worsening of the Arab–Israeli conflict impaired the whole process, blocking advancement of cooperation in the political and security domain and favouring sub-regional frameworks suc...