![]()

III

Cultural Perspectives on parent–child and Family Relationships

![]()

5

Attachment Across Diverse Sociocultural Contexts: The Limits of Universality

MARINUS H. VAN IJZENDOORN, MARIAN J. BAKERMANS-KRANENBURG, AND ABRAHAM SAGI-SCHWARTZ

INTRODUCTION

In this chapter we address the issue of the universality and sociocultural specificity of individual differences in attachment behavior, and we try to examine whether any sociocultural limits to the emergence of organized patterns of attachment can be found. In light of the more than 1200 different cultures (past and present), and at least 186 different cultural areas, any claim to cross-cultural validity of a theory can only be considered a bold but tentative hypothesis. Nevertheless, there is some evidence for the idea that intracultural differences in the development of attachment may be larger than the cross-cultural differences (Van IJzendoorn & Sagi, 1999). The implication of this finding is that we should investigate attachment in diverging sociocultural contexts, in order to maximize the probability of a refutation of the cross-cultural hypothesis, and to test attachment theory to its limits. Here, we broaden our scope and discuss in more detail recent attachment research in Africa, the United States, Israel, and Japan in search of the sociocultural limits of attachment theory.

We begin with a description of attachment networks by taking an evolutionary and sociocultural perspective, followed by a behavior genetics analysis of father-mother-infant attachment security, showing the role of nurture versus that of nature. A number of specific cultures and contexts are then examined: the African case with infant-mother attachment in a network of caregivers; ethnicity versus socioeconomic status in explaining differences in attachment security between African-American and White children; the maladaptive sociocultural context of infants sleeping away from parents at night in Israeli kibbutzim; and, lastly, the notion of attachment and amae in Japan. Analyses and integration of these diverse sociocultural contexts lead us to conclude that attachment is universal and at the same time context-dependent.

Attachment Networks in Evolutionary and Sociocultural Perspective

What Is Attachment?. Children are attached if they have a tendency to seek proximity to and contact with a specific caregiver in times of distress, illness, and tiredness (Bowlby, 1984). Attachment is a major developmental milestone in the child's life, and it will remain an important issue throughout the lifespan. In adulthood, attachment representations shape the way adults feel about the strains and stresses of intimate relationships, including parent–child relationships, and the way in which the self is perceived. Attachment theory is a special branch of Darwinian evolution theory, and the need to become attached to a protective conspecific is considered to be one of the primary needs in the human species. The theory is built upon the assumption that children come to this world with an inborn inclination to show attachment behavior—an inclination that would have had survival value, or better: would increase “inclusive fitness”—in an environment in which human evolution originally took place.

Sociocultural Context of Attachment. The evolutionary background of attachment has sometimes wrongly been interpreted as indicating strong universality of patterns of attachment behavior, and as implying the indifference of attachment theory to the diverse sociocultural contexts in which attachment takes shape. It has been argued, for example, that attachment researchers have been blinded to alternative conceptions of relatedness (Rothbaum, Weisz, Pott, Miyake, & Morelli, 2000). Rothbaum and others argue that it is much too early in this game (learning about human variation in attachment behavior) to assume we know what is universal. Rothbaum suggests that attachment theory suffers from a Western bias, and is not open to the influences of non-Western cultures.

Ironically, empirical research using the concept of individual differences in attachment started in Uganda half a century ago (Ainsworth, 1967), and attachment researchers have ever since been studying the universality and cross-cultural validity of attachment theory. Of course, the innate bias to become attached leads to attachment behavior in almost every exemplar of the species, but in an earlier review on cross-cultural attachment research we emphasized that “from this universality thesis, it does not follow, however, that the development of attachment is insensitive to culture-specific influences … the evolutionary perspective leaves room for globally adaptive behavioral propensities that become realized in a specific way dependent on the cultural niche in which the child has to survive …” (Van IJzendoorn & Sagi, 1999, p. 714).

Patterns of Attachment. Attachment to a protective caregiver helps the infant to regulate his or her negative emotions in times of stress and distress, and enables the infant to explore the environment even if this environment contains somewhat frightening stimuli. The idea that children seek a balance between the need for proximity and the need to explore the environment is fundamental to the various attachment measures, such as the Strange Situation procedure (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall (1978) and the Attachment Q-Set (Vaughn & Waters, 1990). Ainsworth and her colleagues observed one-year-old infants with their mothers in a standardized stressful separation procedure, and used the reactions of the infants to their reunion with the caregiver after a brief separation to assess the amount of trust the children had in the accessibility of their attachment figure. The procedure consists of eight episodes of which the last seven ideally take three minutes. Each episode can, however, be curtailed on request of the caregiver, and the experimenter may also shorten an episode, for instance when the infant is crying.

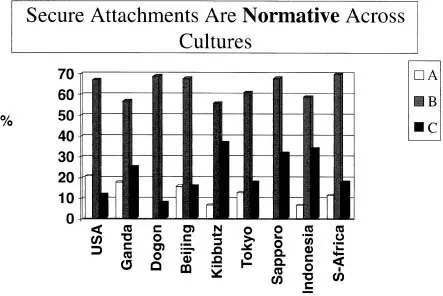

In the Strange Situation procedure, infants between 12 and 24 months of age are confronted with three stressful components: an unfamiliar environment, interaction with a stranger, and two short separations from the caregiver. This mildly stressful situation elicits attachment behavior; three patterns of attachment can be distinguished on the basis of infants’ reactions to the reunion with the parent or other caregiver. Infants who actively seek proximity to their caregivers upon reunion communicate their feelings of stress and distress openly, and then readily return to exploration are classified as secure (B) in their attachment to that caregiver. Infants who do not seem to be distressed, and ignore or avoid the caregiver following reunion (although physiological research shows that their arousal during separation is similar to other infants; see Spangler and Grossmann, 1993), are classified as insecure-avoidant (A). Infants who combine strong proximity seeking and contact maintaining with contact resistance, or remain inconsolable, without being able to return to play and explore the environment, are classified insecure-ambivalent (C). In Figure 5.1 the distribution of attachment classifications across some cultures is presented. In this chapter we focus on attachment studies con ducted in Africa, the United States, Israel, and Japan.

In addition to the classic tripartite ABC classifications Main and Solomon (1990) proposed a fourth classification, namely, disorganized attachment (D). Main and Solomon (1990) used the term disorganized/disoriented attachment (D) to describe patterns of infant behavior during the Strange Situation, which seemed odd and lacked an organized strategy with respect to the attachment figure. Disorganized attachment has been associated with the infant's experience of prolonged or repeated separation from the caregiver. Approximately 80 percent of maltreated infants show this type of attachment. Disorganized attachment is also found with high frequency in infants whose mothers are alcoholics or depressed, and in families with high marital conflict (for a meta-analytic review, see Van IJzendoorn, Schuengel, & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 1999). Main and Hesse (1990) have suggested that infants develop disorganized attachment when they experience the parent as frightening or frightened, and that the essence of disorganized attachment is fright without solution. When the only possible base from which to explore the world (the parent) is at the same time the source of fear, the child is placed in an irresolvable paradoxical situation, with disorganized attachment as a result. Although some cross-cultural attachment studies include the disorganized attachment category, it is not central to the discussion of cross-cultural issues in attachment theory in the current chapter (see Van IJzendoorn, Schuengel, & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 1999, for a meta-analytic review of disorganized attachment).

FIGURE 5.1 Updated from Handbook of Attachment, 1999, p. 729.

Attachment Networks. One of the differences between Western and non-Western families seems to be the number of parental and nonparental caregivers available for the infants. In Western families the mother–infant bond seems to be unique and rather exclusive whereas in non-Western cultures nonmaternal caregivers seem to be important attachment figures. Attachment theory, however, is not biased toward one of these arrangements. Attachment involves part of a persons social network, namely, the affective relationships someone might have with one or more significant others who are considered stronger or wiser and may serve as sources of protection from danger and a safe haven for exploration of the environment. The attachment relationship emerges from myriad social interactions during the first few years of life, usually with the biological mother or with alternative caregivers who are genetically related to the child and interact with him or her on a regular basis. As the evolutionary perspective of attachment theory would predict, fathers, older siblings, or grandparents fulfill important roles as attachment figures in a variety of cultures and in various nonhuman primates (Lamb, 1997; Van IJzendoorn & Sagi, 1999; Hrdy, 1999).

As Bowlby argued in the second edition of the first volume of Attachment and Loss, “the survival of the genes an individual is carrying must always be the ultimate criterion when biological adaptedness is being evaluated” (1969, p. 56). Attachment should be evaluated from the perspective of reproduction of the genes in future generations; it was evident to Bowlby that not only the tie to the biological mother but also emotional bonds with biologically related protective others could serve this function. “Inclusive fitness” (Trivers, 1974) means that reproduction of one's genes may be promoted through promoting the survival of one's own offspring, but also by promoting the reproduction and survival of any other kin who is likely to be carrying the same genes (Belsky, 1999).

Attachment theory is quite clear-cut about the role of the biological mother, and one of the most important experiments in the history of attachment theory—Harlow's rhesus monkey experiments with wire-mesh and furry-clothed artificial mother figures—showed how the biological functions of child-bearing and feeding are separate from that of protection (Harlow, 1958). For Bowlby, the biological mother is not necessarily the most important attachment figure; early in his work on attachment he remarked that whenever he used the term “mother,” “[I]t is to be understood that in every case reference is to the person who mothers the child and to whom he becomes attached” (p. 29). From his trilogy it was also clear that more than one person may play the role of attachment figure. Therefore, it is somewhat disappointing that attachment theory is still misinterpreted as exclusively dyadic, monotropic, and mother-fixated (Tavecchio & Van IJzendoorn, 1987; Van IJzendoorn & Sagi, 1999).

Alloparenting. What factors promote the involvement of attachment figures other than the biological mother in nonhuman primates? In her book on “Mother Nature,” Hrdy (1999) coined the term alloparenting to indicate the care provided to the infant by biologically related nonmaternal caregivers. Hrdy demonstrated that our species may well have evolved to become dependent on maternal as well as alloparental care for its infants. Mothering should be supported by nonmaternal care in order to share the heavy burden of raising human infants. As Hrdy argued, at least three factors are important in enhancing the role of older siblings, grandparents, or fathers as attachment figures.

The ecological factor concerns the necessity for mothers to be near the infant in order to provide for hunger and thirst in environments that have only scarce resources. If the infant does not run the acute risk of starvation or dehydration there...