![]()

1

HALFORD MACKINDER AND THE PIVOTAL HEARTLAND

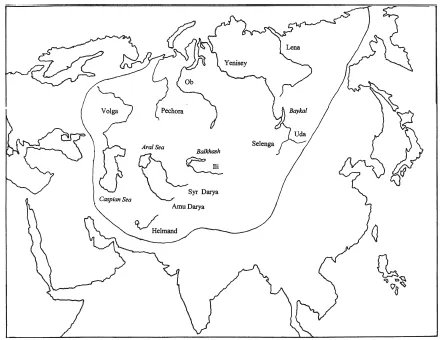

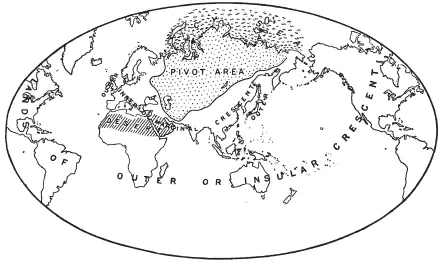

A century ago, Halford Mackinder presented a paper entitled the ‘The Geographical Pivot of History’, in which he set out a central concern of western defence policy – the fear that the landmass of Euro-Asia would be controlled by one power, which would be in a position to exercise global domination.1 Mackinder's Pivot, in ‘the closed heart-land of Euro-Asia’, consisted of the basins of the rivers that drained to the Arctic ocean, together with the regions of internal drainage that fell into the Aral and the Caspian inland seas. The Volga river, which drained the lands between Moscow and the Urals, flowed to the Caspian and was beyond the influence of sea power. Mackinder illustrated the drainage basis of his concept with a map depicting continental and Arctic drainage using an equal area map projection.

The Pivot paper depicted history as a struggle between land power and sea power. In the Columbian era West Europeans, using the oceans, had established control over many parts of the globe. Mackinder predicted the balance would swing back in favour of land power based upon the landmass of Euro-Asia. After World War I Mackinder restated his ideas in Democratic Ideals and Reality (1919). The Pivot was renamed the Heartland and enlarged to include the Black Sea and much of the Baltic, for World War I had shown that sea power could not force its way into the Black Sea via the Dardanelles and the Bosphorus, and Germany had been able to exclude the Royal Navy from the Baltic.

In Democratic Ideals and Reality, Mackinder supported the creation of a new middle tier of European states – the Baltics, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Austria, Hungary, and Yugoslavia – but realized that the new states of eastern Europe would be vulnerable to Germany and the Soviet Union. He issued a famous warning:

Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland:

Who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island:

Who rules the World-Island commands the World.2

Within twenty years of the publication of Democratic Ideals and Reality, the battle for territorial control of eastern Europe developed as Germany remilitarized the Rhineland (1936), absorbed Austria (1938), took German-speaking areas away from Czechoslovakia (1938) invaded the remainder of the Czech lands in March 1939 and did a deal with the Soviet Union to dismember Poland a few days before attacking that country on 1 September 1939.

Figure 1.1 Internal and Arctic drainage in the geographical pivot of history

Figure 1.2 The natural seats of power (from Geographical Journal, 1904, courtesy of the Royal Geographical Society)

Halford Mackinder is one of a small group of political geographers who took an active part in political life and attempted to influence international affairs. The group includes Friedrich Ratzel, Vidal de la Blache, Albert Demangeon, Isaiah Bowman and, notoriously, General Karl Haushofer, who gained a doctorate in geography for work on Japan, but after World War I became a propagandist for German expansion.

Haushofer ran an institute of geopolitics in Munich, wanted revision of the Treaty of Versailles in Germany's favour, the expansion of Germany to include all German speaking peoples – the VolksDeutsche – and the creation of a greater Germany that would control central Europe. Haushofer thought Germany could become a world power by reaching an accommodation with the Soviet Union, and then launching into overseas expansion at the expense of the space owning imperialists – France and Britain. Haushofer's idea of an accommodation with Russia prior to global expansion was derived from Mackinder's Pivot paper.3

Haushofer used to visit and tutor Hitler and Hess at Landsdorf prison where they were detained after the Munich Beer Hall Putsch (1923). Fortunately for western civilization, Hitler did not accept Haushofer's opinion that Mackinder's Pivot paper was the greatest of all geographical world views.4 Hitler's intuition took him in a different direction. Overseas colonies were expensive to run and difficult to defend.5 Hitler wanted lebensraum (living space) in the east where Nordic communities could be established to exploit the grain fields of the Ukraine, the ores of the Urals, and the forests of Siberia. As Hugill describes in this volume (Chapter 7), here is the strategic problem that Mackinder referred to in 1919. Was Germany going to take territory in the east or become a maritime power in the west? Germany never resolved the strategic issue, fought World War I on two fronts, lost, and was going to do the same in World War II.

However, the first phase of Nazi expansion fitted Haushofer's world view. In 1938 the absorption of Austria and the Sudetenland brought German-speaking areas into Germany. Haushofer was less pleased, in the spring of 1939, when the take-over of the remaining Czech lands brought in non-German people. However, Haushofer's strategic model seemed to be attained on 23 August 1939, with the signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop non-aggression pact. Here was the understanding between Russia and Germany that Haushofer wanted and Mackinder feared.

The non-aggression pact divided Poland, and all of eastern Europe, between Germany and the Soviet Union. On the first day of September 1939, the Wehrmacht attacked Poland. On 17 September the Red Army did the same, and Poland was erased from the map. With the east secure, Germany was now free to attack the west. In the spring of 1940, Denmark was occupied and Norway invaded. Then Belgium and the Netherlands were assaulted. In June, France sued for peace. Western and central Europe were under German control. Britain and the Commonwealth had no mainland allies. Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union controlled much of Eurasia and, in the Far East, Japan had taken over Manchuria (1931) and invaded eastern China, beginning in 1937.

By the end of June 1940, Germany controlled the coast of western Europe from North Cape in Norway to France's border with Franco's Fascist Spain. Before the conquest of western Europe, the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force could watch for war ships coming out of the Baltic and the Elbe. Now German forces could operate from bases that stretched from the fjords of Norway to the submarine pens at Lorient near Bordeaux and the submarines could project sea power across the Atlantic to the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico, and the east coast of the United States. In addition Germany had acquired sources of raw materials and manufacturing capacity in western Europe. France, in particular became a major supplier of agricultural products, raw materials, and manufactured goods to Germany.6

From June 1940 to June 1941, the strategic picture was close to what Mackinder had feared in 1904. An ‘alliance’ with the Soviet Union had allowed Germany, by force of arms, to dominate western and central Europe. The sea power, Britain, was isolated, and the resources of the Continent, including the raw materials supplied to Germany by the Soviet Union, were being used to create a submarine fleet capable of reducing Britain to impotence.

The public in the neutral United States did not see the dangers, and although the Royal Air Force, in the Battle of Britain, removed the threat of a German invasion of southern England, at the end of 1940 the prospects of Britain and her Commonwealth allies – Canada, the Union of South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand – were poor. Britain had to import food and raw materials, and the sea lanes through which ships reached Britain were vulnerable to surface raiders and submarines.

At the end of 1940 Churchill told Roosevelt of his fear that Vichy France would join Hitler's New Order in Europe.7 Had that happened, and the US stayed out of the war, Britain would have been forced to come to terms with a Europe dominated by Germany. The Atlantic would have become an ocean over which the US and Nazi Germany competed for control.

Fortunately for Britain, at the end of 1940, Hitler looked east again, ordering an attack – Barbarossa – on the Soviet Union, which started on the night of 21–22 June 1941. Hess, apparently in an effort to make a deal with Britain, flew to Scotland in May 1941. Nothing came of this initiative, and Hitler was furious with Hess, Haushofer's Nazi party patron. Haushofer's position was weakened by the departure of Hess and his strategic ideas were cast aside as Germany attacked the Soviet Union and abandoned the non-aggression pact. Haushofer spent part of the war in Dachau concentration camp.

Had Hitler allowed his generals to run the campaign in the east, the Soviet Union might have been put out of the war. Many of Hitler's generals wanted to drive east and force a decisive battle in front of Moscow before the end of 1941. Logistically this would be difficult to achieve, but Hitler, anxious to take territory and resources, worsened logistic problems by insisting on spreading armies out on several fronts to Leningrad, Moscow, the Ukraine, the Caucasus, the Volga and Stalingrad.8 The pivotal battle came not in front of Moscow in 1941, but at Stalingrad, at the end of much longer lines of communication, in the winter of 1942–1943.

The German attack on the Soviet Union in 1941 altered the global geostrategic balance. Germany had wars in the west and the east. Hitler hoped that if Germany attacked the USSR, Japan, not having to fear the Soviets, could expand in the Pacific against the US, and America would be unable to help Britain.

By the end of 1941, Hitler's hunches had gone badly wrong. The war in the east was not won quickly. The Soviet Union did not collapse as Hitler expected and, in early December 1941, a Red Army counter-attack stopped the unwinterized Wehrmacht in front of Moscow to freeze in the Russian winter. On 7 December 1941, Japan did attack southeast Asia, and Pearl Harbor. Germany declared war on the US on 11 December. Now German productive capacity was outclassed by American resources of manpower, minerals, foodstuffs, and the ability to mass produce ships, tanks, and planes, even if Germany defeated the USSR. The Soviets, however, moved productive capacity eastward, and destroyed what could not be saved.9 Nazi Germany never extracted the resources from the Soviet Union that it was supposed to gain. Germany got better access to Soviet raw materials as a result of the non-aggression pact than was achieved by the Barbarossa campaign.

By the end of 1941, Hitler was hearing from several advisors, including the armaments minister Todt, that the war could not be won, and a settlement should be negotiated with the Soviet Union. Early in 1942, Todt died in a plane crash. Todt's successor, Speer, increased arms production in 1942, 1943, and much of 1944, but Germany simply could not match the productive power of the US in the west and did not have the manpower to defeat the Soviet Union on the long eastern front.

However, Hitler came much closer than is sometimes allowed to gaining long term control of central and eastern Europe. If in October 1941 there had been negotiations between Stalin and Hitler (and Stalin was apparently prepared to talk about a settlement that gave Germany the Baltics and part of the Ukraine), then the Japanese would not have been sure that the Soviet Union would be wholly engaged on its western front. Japan would not have had the same freedom to expand in the Pacific.10 If Japan had not attacked Pearl Harbor in December, 1941, and had the US stayed out of the war longer, then Germany could have dominated Europe from the North Sea, through the Ukraine, to the Caucasus, posing a threat to the Persian Gulf and the Middle East.

With a cease-fire in the east, Germany would still have kept large armies in the conquered lands, but it would have been difficult for Britain, the Commonwealth, and the United States to invade the continent to destroy Hitler's New Order which was harnessing the resources and manufacturing capacity of western and central Europe in support of the German military. Fortunately, in the fall of 1941, Hitler would not think of a negotiated peace with the Soviet Union.

In Britain and the United States, as it became clear that the USSR was not going to collapse, several commentators made the point that, in defeating Nazi Germany, the western allies should not hand control of Europe to the Soviet Union. Churchill had this view and in the United States, although the State Department was required by President Roosevelt to embrace, for a time, Morganthau's 1944 plan to close the Ruhr and break up Germany, other perspectives had emerged earlier in the war.11

In 1942 the geographer Isaiah Bowman, territorial advisor to President Wilson at Versailles and then President of Johns Hopkins University, told Sumner Welles, at the State Department, that it would be a mistake to break up, or fragment, Germany.12 More publicly Nicholas Spykman, the Yale political scientist, declared in America's Strategy in World Politics (1942) that a ‘Russian state from the Urals to the North Sea can be no improvement over a German state from the North Sea to the Urals.’13 Spykman's American Strategy ...