![]()

Introduction: Unburied Memories

Pedram Khosronejad

PEDRAM KHOSRONEJAD is a Research Fellow in Social Anthropology at the University of St Andrews, Scotland. He holds a Ph.D. from EHESS in Paris. His research interests include the anthropology of death and dying, visual anthropology, visual piety, devotional artifacts, and religious material culture, with a particular interest in the Islamic world. Forthcoming publications include War in Iranian Cinema (I.B. Tauris), and Women’s Rituals and Ceremonies in Islamic Societies (C.I.U. & I.B. Tauris). He is also chief editor of the Journal of Anthropology of the Middle East and Central Eurasia.

Since antiquity, remembrance of heroes and heroic acts has been part of Iranian folklore, history and landscape. Heroes seem always to be present in the battlefields, fighting the enemies of their motherland (mam-e vatan), Persia. Some of their legendary battles and heroic acts are recorded in historical literature, others are visualized in manuscripts, and a few are engraved on the rocks and mountains of this “land of lions” (sarzamin-e shiran).1 Contemporary commemorations of Iranian heroes form a significant aspect of the cultural heritage of Iran (tangible and intangible): war and battlefield memories, commemorations and material culture [Figure 1].

All of the information we have today on Iran, Iranians, and their roles and reactions in wars is based on what was inherited from probable witnesses and the work of historians. Historiographies, collective memories, and tangible heritage clearly demonstrate that Iranians have never accepted or appreciated the political intervention and military aggression of other nations and their policies in Iran, regardless of whether they were Arab, Mongol, Portuguese, Dutch, Russian, British, American or Iraqi.

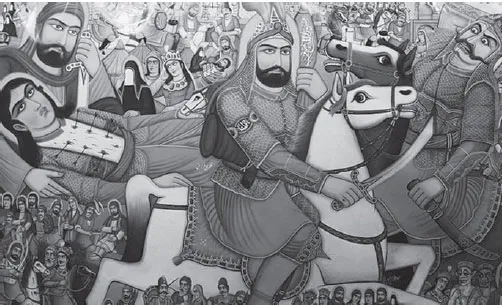

Additionally, some documents and materials in which we find traces of Iran and its warriors confirm that the remembrance of dead heroes and the performance of important public funeral ceremonies in their honor have long been part of the cultural landscape [Khosronejad 2006]. Needless to say, such remembrances have grown since Shiite Islam became the official religion of Iran and the commemoration of the martyrdom of Shiite imams and saints—especially Hoseyn ibn-Ali, the Prince of Martyrs—became part of Iranian religious memorial rituals and performances [Figure 2].2

National bereavement and the commemoration of martyrs were common due to state policy and social demands during and immediately after the Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988), and today modern war memorials and monuments appear throughout the Iranian urban and rural landscape [Khosronejad 2011c; Figure 3].

Figure 1 Rostam is killing Esfandyar. Bas-relief, Mausoleum of Ferdowsi, Tous, Iran. (Photo © P. Khosronejad, 2004; color figure available online)

Figure 2 The scene of the Battle of Karbala. Oil Painting on canvas by M. Farahani. (Photo © M. Farahani; color figure available online)

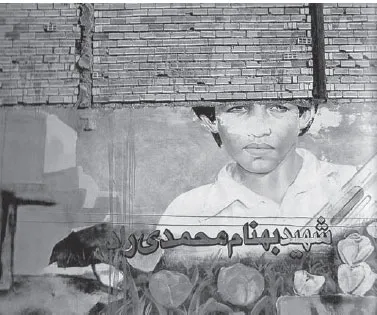

Ten years ago, anyone who walked through the Iranian cities that were the sites of bloody massacres and direct targets of Saddam Hussein’s armies could find traces of terrible, almost unimaginable, human loss. But today such scenes are rarely found, and little by little such tangible material remains of war are disappearing; perhaps because people no longer wish to confront them directly [Figure 4].3

The Iran–Iraq war, referred to by Iranians as “the Sacred Defense and Imposed War” (Defa’e Moqadas va Jang-e Tahmili), began with Iraq’s attack on Iran on September 22, 1980, and ended eight years later, on August 20, 1988, leaving at least 300,000 dead and more than 500,000 injured out of a total population that, by the war’s end, numbered some 60 million.4 Today some Iranian military institutions claim that over 50,000 bodies of volunteer soldiers (razmandeh) remain in the former battlefields of Iran and Iraq [pers. comm.]. Yet despite the 2,920 days of war, this devastating human disaster has been ignored by the West.

Sparse research on the origins of the Iran–Iraq war suggests that the main causes of this bloody event were geopolitical and territorial issues, including the boundaries of the Arvand River (arvandrud)5 and neighboring zones. These studies argue that the war was an extension of the politics of border negotiation by means of military siege [Donovan 2011; King 2007; Swearingen 1988; Wright 1980–1981]. Additionally some observers suggest non-territorial factors. Both explanations are too limited and restrictive: even in combination they fall short.6 Any observer can confirm however that territory and resources were direct geographical factors in the war, and its origins were geopolitical in yet another way: acquiring territory with symbolic value is a primary means of achieving other political goals. The significance of the Arvand River derives from its role as a key symbol in the complex set of rivalries that exist between the two countries [Khosronejad forthcoming; Figure 5].

Figure 3 Public tomb and memorial of six unknown martyrs of the Iran–Iraq war. Bilal Mosque, Vali-asr Avenue, Tehran. (Photo © P. Khosronejad, 2009; color figure available online)

Yet during the eight years of the Sacred Defense between Iran and Iraq events and activities occurred and were shaped in different ways, as some supporters of the Iranian regime argue. They believe that the war was based on territorial issues and began with Iraq’s attack on Iran, but that gradually something new developed within the Iranian fronts to completely shift the war’s identity and ideology from territorialism into the idea of defense—of course, not a simple defense but the Sacred Defense. Thus the earliest war interests of Iranian volunteer soldiers (razmandehgan), based on water and land interests (frontier issues), shifted to identity (hoviyat) and cultural (farhangi) issues. Their new concerns reflected an identity and culture based on and rooted in Shiite Islam, which had been born in and flourished during the Iranian Revolution of 1978–1979.

The scholars who have advanced this theory believe that fighting in such a sacred area (saahat) occurred not only due to potential territorial gain but also for more important things: values (arzeshha) and beliefs (bavarha); ideology, which has its roots in Ashoura and Imam Hoseyn (the Karbala paradigm); and the defense of the oppressed (mazluman) against the oppressors (zaleman) and the corrupt (fasedan). Defenders of this theory of the Sacred War argue that these values and ideologies (and revolutionary slogans) completely changed all of the previous strategies, techniques and values of all wars and fronts.

Figure 4 Mural painting of Behnam Mohammadirad, Khoramshahr, Khuzestan. (Photo © M. Monem, 2007; color figure available online)

Figure 5 War and martyrs’ memorial beside the Arvand River, Khoramshahr, Khuzestan. (Photo © P. Khosronejad, 2009; color figure available online)

In such a war the definitions of a martyr and martyrdom are not just a title or a simple religious term used for those who died during war; they represent sacred positions (maqams) and celestial (qodsi) wishes that simply cannot be reached by everyone. Only when one arrives at that state of sincerity (kholus) and perfection of the soul and the spiritual awareness (kamal-e ruhi va ma’anavi) can one be named a martyr. Terms such as endeavor (mojahedat), victory (nasr) and triumph (piruzi) had special and non-materialistic meanings, and were mostly used in cases of volunteer soldiers fighting with their soul (nafs) and an exalted spirit (ta’aliyeh ruhiyeh). Therefore formal (zaheri) activities such as fighting on the fronts became a religious duty (aday-e taklif), not just a war (jangidan). Behind all of their activities on the fronts (fighting and enduring hardship), volunteers who could attain the real state of a basiji were seeking to fight the temptations of their own soul (khod) and thus exalt their spirit [Shamqadri 2011].

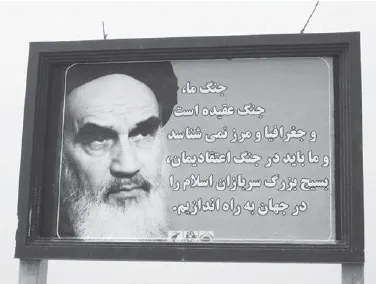

In this regard Avini argues that “war was the most important problematic of all Iranians who believed in the Islamic Revolution under the leadership of Imam Khomeyni, so their lives and the life of Islam were directly connected to the result of that Sacred Defense. The presence of Iran in that war was not to prove her power or just a simple fight with Iraq.” Avini believes that the Iran–Iraq war was a battle (nabard) between justice (‘edalat) and truth (haq) against injustice (zolm) and vanity (batel). “Therefore it was unimportant to us whether waging war was a good or bad thing” [Avini 1999: 201; Figure 6].

The theme of martyrdom, central to the Iranian Revolution, became much more important and received further political dimensions and ideological values during various periods of the Sacred Defense. Thousands of Iranians—male, female, children, youth and the elderly—were mobilized during the eight years of war and trained for it; martyrdom was “propagated and glorified as a psychological means of securing support” for the Sacred Defense [Zahedi 2006]. Political leaders urged women to encourage males in their family to take part [Paidar 1995: 305]. Thousands of women also trained as combat soldiers and fought in the war [Reeves 1989: 8]. Furthermore millions of young civilian men, secular or religious, volunteered to fight at the fronts to defend their motherland.

Figure 6 “Our War is an Ideological War which doesn’t recognize any geographical or frontier limitations. Therefore for such ideological war, we should create and mobilize the great army of Islam in the world” (R. Khomeyni). Billboard, Shalamcheh Battlefield Site, Khuzestan. (Photo © P. Khosronejad, 2009; color figure available online)

Sacred Defense martyrs had diverse ethnic, religious and class roots, the majority of them coming from low-income backgrounds or rural areas all over Iran.7 Urban martyrs were largely from the traditional middle class and held strong religious beliefs [Zahedi 2006: 272]. Some were members of opposition groups who joined the war due to their secular belief in fighting for the motherland, while others were members of other religious groups, including Jewish Iranians, Armenian Iranians (Orthodox Christians), and Assyrian Iranians [Zahedi idem]. Many other young men participated who believed neithe...