![]()

An introduction to

feature film development 1

The level of awareness about the strategic role of development across much of the European film industry has risen in the last 5 years. The Media Business School (MBS) research upon which this book is based examined national and pan-European funds, the private sector, broadcasters, and certain training initiatives. The results of that research indicated that public funds such as the European Script Fund (SCRIPT), alongside initiatives implemented by the MBS such as ACE – Ateliers du Cinéma Européen and PILOTS (the Programme for the International Launch of Television Series), have helped change the perception that development was merely an irritating starting block, while the main business of films was to be found in the production process.

The political environment has also moved forward. In the 1994 European Commission’s Green Paper on Audiovisual Policy a diagnosis of the structural shortcomings of the European programme industry argued that: ‘At the creation stage, European projects are handicapped by a lack of development. This is the crucial stage where original ideas must be reworked and geared towards wider audiences’.

The diagnosis went on to argue that it was ‘regrettable that some public support mechanisms are unduly restricted to domestic production and do not give sufficient incentive to work for European and transnational markets. This creative/development stage is essential: even with the most sophisticated distribution mechanisms, if no account is taken of the audience’s tastes and demands, the European film industry will never be competitive’.

Hence, support for development activity was underlined as a priority sector for the future building of the European audiovisual industry.

1.1 THE WIDER PERSPECTIVE

Erope currently has an annual audiovisual trade deficit of more than $3.7 billion with North America. US-produced films and programmes are currently taking around 80% of Europe’s cinema box-office revenues and 40% of Europe’s television audience ratings.

Among the different approaches and cost structures of the different industries, there is one area where the US spends significantly more than Europe: development. Around 7% of the US’s total audiovisual revenue, and up to 10% of each film’s budget, is invested on development. In stark contrast, Europe tends to spend a much lower percentage, estimated at between 1 and 2% of each film budget.

1.2 DEFINING THE ACTIVITY OF DEVELOPMENT

Development is the chronological starting point for all producers, writers and most directors when entering the film industry. It is the place from where ideas should be stimulated and encouraged to grow, and where initial deals are made. As such, it is a fundamental bedrock to subsequent film activities such as production, distribution and marketing.

For the purposes of this book, the activity is defined as the work surrounding the initial screenwriting process, the raising of finance and the initial planning of production. In addition to the writing of treatments and full screenplay drafts, development activity includes the time and money spent in building a project, attracting talent and the marketing of a concept to potential financiers. It is not normally seen as part of the pre-production process where locations, casting and line budgets are prepared. However, in certain cases scripts are further developed, perhaps because of casting or director’s requirements.

1.3 THE EARLY STAGES OF DEVELOPMENT

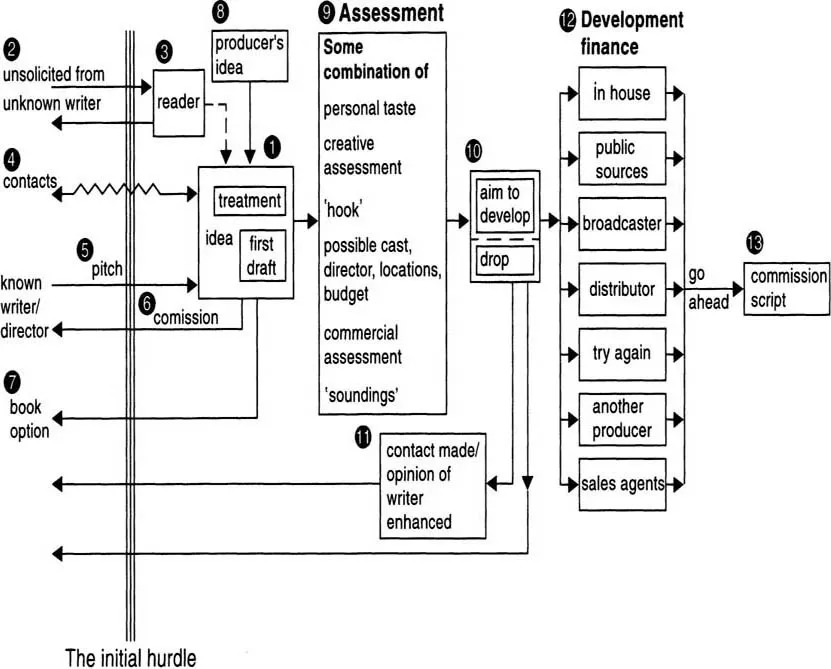

The initial idea stage is a loosely structured area with a considerable number of possibilities. An idea may take a variety of routes towards a full script commission. The flow chart in Figure 1 shows some of the different routes that can be taken.

The initial idea of a script [1] can be an idea, treatment or first-draft script. Unsolicited scripts from unknown writers [2] will in the majority of instances move through to a reader first [3]. Most of them will be rejected. A very small percentage will come through as an idea [1] from development. Ideas also come from contacts [4]; a pitch by [5] or commission to [6] a known/established screenplay writer; or from the buying of a book option [7]. A large number of producers also generate ideas themselves [8].

The producer will then assess [9] the basic idea. On this basis the producer may decide to go ahead with development, or to drop the project [10]. However, the originator of an idea may have benefited from the contact, even if the idea did not make it any further.

To develop an idea, a producer will need to secure finance [12]. This can come from an in-house source, from a public development fund, a broadcaster, a sales agent, a distributor or a private investor. However, the last three sources are often rare in the European film industry.

Figure 1 The ideas stage

Source: NFTS

The producer also has to make a commitment in terms of time and planning, often incurring considerable expense through travelling to potential financiers, markets and festivals. They will have to put a development budget together at this stage. In addition, another producer or potential co-financier may help with development finance. Once the finance structure has been at least part-raised, the idea will move into a fully-fledged development stage. This normally includes a first draft, two re-writes [13] and the active raising of finance around the growing package.

1.4 DEVELOPMENT AS A HIGH-RISK INVESTMENT

Figure 1 may give the impression that there is a straightforward, typical standard for developing ideas. However, the truth is that feature film development is an inexact science. While there are many ways to move a project toward production, one element remains consistent throughout Europe: development is a high-risk stage of film production. There are no guarantees of a project’s successful journey from idea through to treatment and drafts, from screenplay to production, on to distribution and exhibition, and to what should be the ultimate goal: an audience.

It is also a relatively expensive area of risk investment. For example, a European film with a budget of ECU 2-3m may cost between ECU 50 000 and 150 000 minimum to develop. Large-budget films by European standards of around ECU 8-10m may cost as much as ECU 250 000 to move through development and into production.

A decade ago, the development process within Europe’s film industry was a poorly defined, secondary element to the notion of entering film production. Indeed, most practitioners would have assumed that development had something to do with scripts, and left it at that. Scripts, and the writing of them – albeit not necessarily the development of them in the fuller sense of the activity – became the focal point for the early stages of film production.

The surrounding but strategically central elements to the script itself tended to be side-stepped or simply not recognized. These include research and acquisitions of rights for source material, treatment development, the raising of finance, the marketing of the package, the attachment of talent and the costs of paying script editors or hiring additional writers.

Historically, the European producer has traditionally looked at the development costs against the projected return from fees and retained rights. The preoccupation with production has partly stemmed from the fact that when producers are in production, they are being paid. This approach has tended to obscure the financial and practical elements essential to a healthy development process. It has also led the producer to take a less realistic view of the projected ‘value’ of a project and how to realize that value in the marketplace.

1.5 THE ‘AUTEUR’ PROBLEM

Part of Europe’s problem regarding development is an historical one and stems from a very strongly developed ‘auteur’ culture, where film directors have enjoyed most of the power in the film-making process. The results of this dependence have led to feature films tending to be rescued in the cutting room by film editors rather than script editors before the main money was ever spent. European writers have tended to be marginalized by the auteur system, while producers also lost out and have been traditionally seen as financial servants for directors. Most experienced writers, script editors and agents suggested to the author that Europe’s producers are often underskilled when it comes to script reading and editing.

For further evidence, it is instructive to turn to the findings of the MBS research. The majority of film producers interviewed for the MBS study were astonishingly vague about their levels of development spending and strategy. Producers replied to the direct questions asked in one or more of the following ways:

1. | They did not know how much they spend on development per year. |

2. | They had no idea what they were spending on development 5 years ago. |

3. | They could normally only estimate how much they had spent on each individual project. |

1.6 EUROPE’S DIFFERENT APPROACHES

Significantly different attitudes toward and understanding of development were apparent from territory to territory, and region to region. At their most basic, it was clear that the UK and Ireland have been influenced to an extent by a largely shared language and links with North America. As a consequence the UK has, at first glance, a fairly advanced notion of what development means. Writers’ agents also play a major role in the development process in English-speaking territories (see Chapter 2).

France has been heavily influenced by the director-led, ‘auteur’ approach. Experienced writers are much more rare than directors who also write their own scripts. And producers tend to concentrate on tapping a subsidy system that tends to reward film-makers when actually in production, and not at the development stage.

Germany has an extensive script-support system in its regional public subsidy network. However, this has tended to be limited to the production of scripts, rather than the fully-fledged development of projects intended for an audience. The result has been a high number of scripts written, but significantly fewer produced at a standard that has attracted audiences in Germany, let alone across Europe or the rest of the world.

Most significantly, southern European territories share a distinctly less conscious notion of feature film development. This is due to a combination of factors. Italy and, to a lesser extent, Spain have been heavily influenced by ‘auteur’ trends. Screenplay writers (and editors) are not regarded as essential to the film-making process, with directors normally assumed to be the writers in most cases. The Italian subsidy system offers no financial support at the development stage, while Spain has only recently begun to consider development support, and even that is in relatively small amounts.

1.7 THE HOLLYWOOD APPROACH

How does the situation in Europe compare to that in Hollywood? Any comprehensive notions of a fully-fledged, integrated development process were, and still are, generally found within the Hollywood studio system, as opposed to Europe’s far more fragmented film environment. Europe’s independent film-makers lack Hollywood-type studio infrastructures. They rarely have the capital with which to invest in development. Individually run companies are forced to drive their ideas and scripts up from the bottom, and the potential for a national film producer to recoup the costs of a production from that territory alone are almost impossible. Europe’s domestic markets are simply not large enough to recoup costs.

‘On-the-block’ development deals – where a production company is attached to a studio – hardly exist in Europe, mainly because there are no studios operating on the same scale as in Hollywood. The exceptions include PolyGram Filmed Entertainment, Chargeurs, Sogepaq and CiBy 2000, but across the continent they are virtually extinct.

A major studio or film production company with a regular output of films tends to view development as a fixed cost within its overall business plan. A portion of this expenditure is allocated to each film as an above-the-line cost. In Hollywood, the development costs are placed at around 8-10% of a film’s total budget. Hollywood’s development:production success ratio is very low, with only around one in 20 projects finally reaching production. As ACE Director Colin Young points out: ‘A huge number of films are put into development in the US, but they never actually reach production. This system is considered fine by the major Hollywood studios and is clearly one reason that explains the studios’ huge overhead cost of making a film’. Put simply, the successful films that go on to make a profit repay the costs of unmade scripts and projects. Profits are then pumped back into the development system, and the cycle of production is continued.

The US film industry’s development budget was placed at around $500m a year by professionals. That is what Europe is competing with’, explained producer David Puttnam. ‘It administered by very experienced executives working at an energy level almost unknown in Europe. It is fed by a very aggressive and well-run agency system at every level. The process is on a different planet’.

1.8 PRIVATE SOURCES OF DEVELOPMENT

Given the highly mature, industrial nature of the Hollywood studio system, it is understandable that the system attracts considerable levels of private investment. In contrast, the MBS research on European development underlined the structural weaknesses that continue to haunt the European film industry. Private development sources remain very hard to attract. The problem appears to lie not just in the levels of money available for investment, but in the incentives being offered. The risks involved in feature film development are very high, hence private financial investors expect ...