![]()

Governance and Development: changing EU policies

Wil Hout

ABSTRACT This introductory article to the special issue on European Union, development policies and governance discusses how notions of (‘good’) governance have come to dominate development discourses and policies since the mid-1990s. The article argues that governance was part of the so-called Post-Washington Consensus, which understands governance reform as part of the creation of market societies. Although academics have commonly emphasised the fact that governance concerns the rules that regulate the public sphere, the dominant understanding of (good) governance in policy circles revolves around technical and managerial connotations. The second part of the article introduces some important features of EU development policy, and argues that this is essentially neoliberal in nature and favours a technocratic approach to governance reform. The EU’s main instrument in relations with developing countries is the Country Strategy Paper, which includes a set of governance indicators for the assessment of the political situation in partner countries. In addition, the European Union has developed a ‘governance profile’, which consists of nine components.

Since the mid-1990s conceptions of governance have occupied a central place in development discourses and policies. Academically the rise of the governance concept can be attributed, to an important extent, to the institutionalist wave that has swept across the social sciences.1 For the policy world the emphasis on institutions and governance in the so-called new institutional economics, and the embrace of the latter by the World Bank, was highly relevant. Governance came to the rescue of neoliberal approaches to development, which were experiencing a crisis as a result of the failure of ‘market-fundamentalist’ structural adjustment policies.2

The adoption of governance into the vocabulary of development has, in the words of some observers, been interpreted as a change from the market-based ‘Washington Consensus’ to an institution-oriented ‘Post-Washington Consensus’. As famously argued by former World Bank chief economist Joseph Stiglitz:

the policies advanced by the Washington Consensus are not complete, and they are sometimes misguided. Making markets work requires more than just low inflation; it requires sound financial regulation, competition policy, and policies to facilitate the transfer of technology and to encourage transparency, to cite some fundamental issues neglected by the Washington Consensus.3

The argument adopted by Stiglitz and others was that attention tor governance and institutions had proven to be a necessary complement to the building or deepening of markets. Thus, it was argued, specific institutional frameworks were necessary counterweights to ‘market failure’.

The reasoning that the focus on governance represented a change away from market fundamentalism has been challenged by various scholars.4 They argue that the Post-Washington Consensus is essentially neoliberal in character, as it continues to see the market as the pre-eminent, fundamentally benign force of development, and the state as subject to the interest of rent-seeking actors.

One of the main implications of the adoption of the governance concept into the neoliberal development framework, which perceived governance as a function of the building of markets, is that it came to be understood in predominantly technocratic terms. As the World Bank has put it, ‘the ability of the state to provide institutions that make markets more efficient is sometimes referred to as good governance’.5 Thus, ‘good governance’ seeks to ensure efficiency in public administration and public finance management, rule of law, decentralisation and regulation of corporate life, including competition laws and anti-corruption watchdogs, arms-length procurement processes and the outsourcing of public services and supply. Conceived as a form of authority outside politics and the traditional realm of administration, it is a means to claim autonomy for technocratic authority from what are seen as distributional coalitions.

The ‘good governance’ approaches of development agencies tend to take one of two forms. The first of these approaches has been taken by those agencies that interpret governance quality as a prerequisite for the effectiveness of development and associated aid instruments. This use of governance has its origins in the analyses of Burnside and Dollar on aid effectiveness. According to these two World Bank analysts, development assistance would be effective only in countries that have adopted good governance and good policies.6 Various development agencies have applied this logic since the late 1990s with the adoption of selectivity principles in aid allocation. For example, the World Bank implemented performance-based allocation of loans and grants given by its International Development Agency (IDA), while the USA adopted the Millennium Challenge Account.7 The European Union has moved in this direction to a certain extent with the adoption into the African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) framework of a ‘governance incentive tranche’, which should lead to allocations of aid funds on the basis of the governance situation and reform commitments in recipient countries.8

The second approach to ‘good governance’ has been applied by agencies that take the improvement of governance and the strengthening of institutions as the prime target of assistance policies. This position is located more squarely within dominant development policies, which see the building of (state) institutions as a major objective of foreign aid. As was the case with the first approach to governance discussed above, these policies find support in the strategy advocated by the World Bank, namely that ‘effective aid supports institutional development and policy reforms that are at the heart of successful development’.9 The EU’s orientation to this approach can be found, among others, in the recent identification of issue areas where European Community aid was felt to have clear value added, and which mentioned ‘institutional capacity building’ as the sixth target.10

The dominant understanding of (good) governance in policy circles fails to recognise the essentially political character of governance issues, which relate to existing power relations in society and concern ‘the formation and stewardship of the formal and informal rules that regulate the public realm, the arena in which state as well as economic and societal actors interact to make decisions’.11 Problems such as the access of marginalised groups to political decision making or the attempts of powerful groups to manipulate governance reform to their advantage have generally received much less attention from the development agencies than have public sector reform, public finance management and decentralisation, to mention but three popular issues.12

Europe as a development actor

This special issue of Third World Quarterly takes stock of the ways in which one of today’s most important development actors, the European Union,13 has implemented policies related to governance in its external development relations. The thrust of the argument presented in the following contributions is that EU development policies are essentially neoliberal in character and that their governance-related strategies in effect display a technocratic orientation and are instrumental to deepening market-based reform in aid-receiving countries.

EU development assistance

In recent years the European Union has become one of the major multilateral agencies in the field of development assistance. Not counting the aid flows originating from the EU member states, European development assistance increased to $11.6 billion in 2007, which amounted to over one-and-a-half times the aid provided by the World Bank through its IDA window in the same year.14 The three main objectives of EU development assistance, according to article 177 of the Treaty Establishing the European Community, are:

the sustainable economic and social development of the developing countries;

the smooth and gradual integration of these countries into the world economy; and

the campaign against poverty.

EU development assistance policies are seen as ‘complementary’ to those of the member states.

The main target of EU development policies has traditionally been the group of member states’ former colonies in Africa, the Caribbean and the Pacific (commonly referred to as ACP countries). After an initial period in which contacts with the former African colonies were regulated by the ‘Regime of Association’ (1957) and two Yaoundé Conventions (1963–75), European relations with the ACP have been governed by four Lomé Conventions (1976–2000) and by the Cotonou Agreement (since 2000), which included aid and trade instruments. Institutionally support for the ACP countries has been financed through the European Development Fund (EDF), which is replenished periodically by the EU member states.

Aid to the ACP countries has continued to account for a sizeable proportion of total EU development assistance. Since the coming into force of the Cotonou Agreement, aid to the ACP has increased from slightly under €2 billion in 2001 to €4.8 billion in 2008. ACP’s relative share in EU external assistance has remained more or less stable, at 35.4% in 2001 and 37.8% in 2008. In 2005 member states pledged €22.7 billion to the European Development Fund, to be allocated to the ACP countries between 2007 and 2013.15

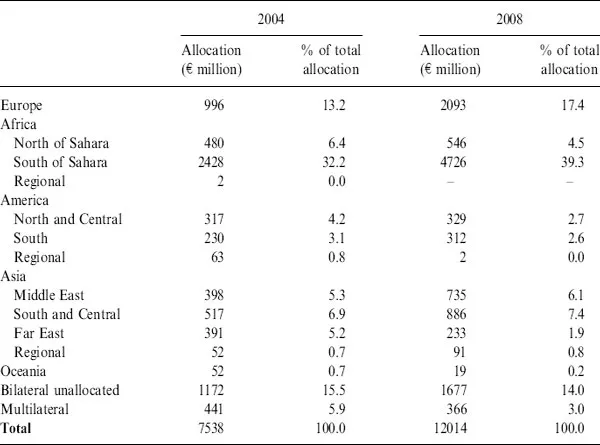

Apart from its agreements with the ACP, the European Union has maintained relations with most other regions in the developing world. Assistance to non-ACP countries is not financed out of the EDF, but is included in the regular EU budget for development aid, usually referred to as the Development Cooperation Instrument (DCI). Particularly important is the EU’s European Neighbourhood Policy, which covers such diverse regions as the Middle East, North Africa and six former Soviet republics in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus. Table 1 shows that the EU’s external assistance has retained its focus on these countries: aid to countries in the Middle East increased from 5.3% to 6.1% between 2004 and 2008, while Eastern European countries saw their share grow from 13.2% to 17.4%. The share of North African countries decreased in relative terms (from 6.4% in 2004 to 4.5% in 2008), although the absolute amount of aid to this region grew by roughly 14%. Aid to Asian countries (excluding the Middle East) fell in relative terms from 12.8% of total European aid in 2004 to 10.1% in 2008. Although the EU has developed ideas on a partnership with Latin America, the share of EU aid flowing to countries in this part of the world has dropped from 8.1% in 2004 to 5.3% in 2008.

TABLE 1. Regional distribution of aid commitments to developing countries (ODA), 2004 and 2008

In terms of policy formulation, the European Council and European Commission have exhibited much activity in the area of development cooperation since the turn of the century, as evidenced by a joint statement on development policy issues in November 2000. This declaration focused on poverty reduction as the ‘principal aim’ of the EU’s development policy and highlighted the need to ‘refocus’ its activities to a limited number of sectoral priorities in order to enhance impact. EU development assistance was argued to provide value added in the following six...