- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Southeast Asian Minorities in the Wartime Japanese Empire

About this book

The Japanese invasion and occupation of southeast Asia provided opportunities for the peoples of the region to pursue a wide range of agendas that had little to do with the larger issues which drove the conflict between Japan and the allies. This book explores how the occupation affected various minority groups in the region. It shows, for example, how in some areas of Burma the withdrawal of established authority led to widespread communal violence; how the Indian and Chinese populations of Malaya and Thailand had extensive and often unpleasant interactions with the Japanese; and how in Java the Chinese population fared much better.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Southeast Asian Minorities in the Wartime Japanese Empire by Paul H. Kratoska in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Ethnic Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

The Japanese Imperium and South-East Asia

An Overview

South-East Asia is a region of multiple and often complex ethnicities. The simplifying strategies of its European colonizers-their practices of ‘racial’ classification and boundary-drawing-only spawned new and often hybrid identities at every margin. One of colonialism's most visible legacies, however, in this region as in others, was the creation of ‘majority’ and ‘minority’ communities within new political collectives. Millions of South-East Asians found themselves (and find themselves still) in the status of ‘minorities’, with the multiple insecurities that designation generally implies. ‘Majority’ status, on the other hand, could be demographically fragile and unreflective of political or economic influence, especially as the colonizers often assigned minorities special and often privileged functions.

In the course of a few months in 1941–42, all of South-East Asia fell suddenly under the rule of Imperial Japan, a country where the concepts ‘majority’ and ‘minority’ had little official or common meaning. Moulding a hegemonic ‘racial’ identity to overcome deep regional, class and caste divisions, Japan's nineteenth century nation-builders had left the country ill-prepared-arguably less so than the European imperial powers to encounter and conceptualise diverse ethnic identities. The conquering army that sailed south in 1941 under the slogan ‘Asia for the Asians’ was convinced above all of its own ‘racial and cultural’ homogeneity, and of the identity of each of its soldiers as sons in a ‘family state’ under a father-god. It was far less certain, and would remain so, about the meaning of ‘Asia’.

Accounts of the Japanese occupation of South-East Asia are usually organized around particular colonies, or even post-colonial nation-states. Partly this reflects the brevity of the Japanese presence; the inability of a new Japanese regional map to take lasting cultural hold. Just how ‘new’ the geography of Japanese empire in South-East Asia actually was, however, remains problematic. While the borders defining European colonies melted with Japan's pan-regional advance, the entities they defined did not simply collapse. The structures of the middling and lower colonial bureaucracies – from administrative systems to indigenous personnel generally survived, as they had to for life to carry on. The bureaucracies, along with a plethora of less formal yet no less tangible structures religious, economic, and social were co-extensive in most cases with distinct ethnic communities, some pre-dating colonialism and others constituted, if not sustained by it. These local infrastructures not only remained the primary interface between the new rulers and the ruled, but also became sites where Japanese and South-East Asians had some of their most intimate, banal, frightening, daily, clarifying, and confused encounters.

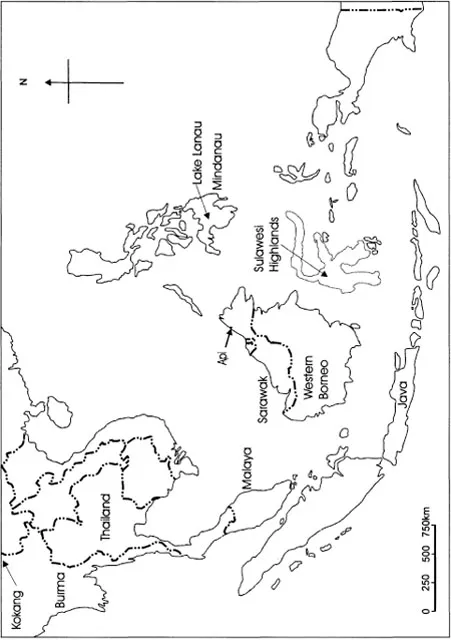

Map 1 South-East Asia showing locations discussed in the book

Each local community would have its own reactions to, and relationships with, Japanese rule. But the very dynamics of community-formation would also change under occupation, as the Japanese sought, like the Europeans and Americans before them, to bring disturbingly complex and alien societies to order through their own simplifying devices. For minorities in particular, the new ‘facts on the ground’ could be highly destabilizing, depending on the closeness of their relationship to the former colonizers, to surrounding majority populations, and to the inchoate plans, fantasies, and anxieties of the local Japanese command. Would they be singled out, or made to disappear into new collectives? Would existing privileges remain or be withdrawn? Would they even be understood by a foreign power that knew little or nothing of local history and lacked the means and interest, in most cases, to find out?

There is now a relatively large literature on Japanese colonialism, the Imperial Japanese Army, and Japanese Occupation policy in South-East Asia, much of it institutionally-based. There is a less well developed but growing historical literature on Japanese constructions of ‘race’, ethnicity, and polity, little of which, unfortunately, touches directly on the South-East Asian Occupation. The following paragraphs will attempt to blend observations from both literatures, providing needed background if not fine-grained answers for certain behaviours of the ruling Japanese ‘minority’ between 1942 and 1945.1

Historians’ narratives of the Japanese occupation of South-East Asia often reproduce, if only implicitly, those of the German occupation of Europe. Overseas Chinese sometimes play the role of the Jews, for example, and the Kempeitai that of the Gestapo. The reasons for this and other similarities in narrative construction are not hard to grasp. Both German Europe and Japanese South-East Asia were seized in a ‘lightning war’ by conquering powers who deployed racialist ideologies and brutalized civilian populations. Moving beneath these generalizations, however, a ‘common frame’ for both occupations tends to obscure more than it reveals, particularly in the matter of social policy or the administration of subject peoples. The Germans planned their advance, particularly to the East, with policies of social re-ordering, colonization, and concomitant genocide very much in mind. From nearly the beginning of hostilities, crucial resources were actually removed from their war effort in order to classify and physically relocate large civilian populations in occupied lands.

The Imperial Japanese Army and Navy advanced to the South mainly to gain control of its raw materials, and to encircle China, the two goals being intimately related. The peoples of South-East Asia and most of the land they occupied were of comparatively little interest to the conquering power. Japan's enemies, by mid-1942, were all located outside the region, or at its peripheries. What Japan demanded over most of Nanpo (the Southern region), apart from natural resources and the labour to exploit them, was quietude an utter acquiescence to Japanese military rule and manipulation.2 Japanese ambitions in both their short-term and meta-historical forms did not lie primarily in South-East Asia but on the Asian mainland opposite Japan. While the peoples of occupied Europe, particularly in the East, suffered from a murderously detailed fascination on the part of their German conquerors, the peoples of South-East Asia more often suffered from a murderous neglect and ignorance on the part of the Imperial Army and Navy.

Lebensraum for Japan was Manchuria, not South-East Asia, which was considered by most Japanese to be exotic, far away, and perhaps uninhabitable. It is true that military planning documents of the 1930s, when official interest began to turn South, mention South-East Asia in the context of Japan's ‘population problem’. Two of the largest Japanese communities outside the Empire were indeed in Singapore and Davao, and smaller numbers of Japanese lived in cities and towns throughout the region. By the time of the conquest, however, colonisation plans for Manchukuo had become so extensive that an Army planning document of 1942 suggested sending mainly Koreans to the South in order ‘to restrain their advance into Manchuria and China’ in competition with Japanese. The ‘Yamato people’ were given the role of shujin minzoku (master people) in the region, but seem to be described, in this document and others, as a small leader-class rather than as numerous peasant settlers. In contrast to Manchukuo, the emphasis in discussions of the South was always on resource extraction rather than resettlement.3

For all its remoteness, however, the South was not without identity in Japanese geography and even mytho-history. The contemporary ‘South-East Asia’ was a term only crafted by the wartime Allies around 1943, and then to describe the Japanese-occupied region to be liberated. Japanese geographers, however, had already conceptualised and named this ‘South-East Asia’ (Tonan Ajia) at least two decades earlier, when Japanese commercial and political interests turned their gaze from the mainland to the sea-lanes in the aftermath of WWI. The construction of ‘South-East Asia’ was related to the 'southern advance’ (nanyo rosbin), a Japanese concept with a long and complex history but framed in the interwar period as the inevitable consolidation of the region's famously rich resources under Japanese economic control.4

This unified ‘South-East Asia’ was, however, a comparatively late invention. Since the Meiji period, Japanese geography had more commonly split the region into a mainland of former Chinese vassal states (roughly equivalent to ‘Indochina’) and an expanse of islands called Nanyo, literally cThe South Seas’. In many Japanese accounts, The South Seas swept uninterrupted from the Malay Peninsula and the archipelago all the way through Oceania, or across geographies which Euro-American mapping tended to separate. A major characteristic of The South Seas was its historic remoteness from Chinese influence, which rendered it both repellent (primitive or savage) and attractive (simple and fresh, somewhat like mytho-historic constructions of ancient Japan).5 Indeed, the region figured prominently in Meiji-era debates on whether Japanese were ‘Mongolians’, and thus kin of Koreans and Chinese, or ‘Malays’, and thus from the beginning an island people quite distinct from mainlanders. The construction of the Japanese as a ‘South Seas’ people would subsequently be used to suggest racial solidarity between Japanese and the inhabitants of the East Indies, although its original intent was not so much to build new ethnic bridges to the south as burn down old ones to the west, that is, distance the ‘Yamato race’ from Koreans and Chinese.6

The theory of a southern ‘racial origin’ for the Japanese came to be incorporated into occupation-period language, however, and may have contributed to occasional Japanese favouritism toward Malays in colonial administration. General Imamura relates in his memoirs how, on being asked by a friendly village elder, shortly after the invasion of Java, why the Japanese looked like Javanese, he told the man 'some ancestors of the Japanese came from these islands in boats. You and the Japanese are brothers.’ Imamura conducted a relatively 'soft’ occupation of Java until his transfer in late 1942.7

The remoteness of South-East Asia from the home islands combined with the legend of the southern origin of the Japanese ‘race’ might have suggested an easy acquiescence on the part of Occupation authorities to South-East Asian nationalisms, or at least autonomy. Yet there was little official Japanese discussion about, let alone encouragement of, a political role for South-East Asians prior to 1943, when the war was beginning to turn and the military sought (too late and too hesitantly, it turned out) to cement relations with local majority elites in the face of an almost certain Allied counter-offensive. Why, it has often been asked, did the Japanese authorities not take their own slogan ‘Asia for the Asians’ more seriously? Why did the Japanese military leave the region having misunderstood and made enemies of so many of the peoples it had come to ‘liberate’? Why could the Japanese not see, until it was too late, the potential for turning indigenous populations into true allies in a pan-Asian, anti-colonialist war?

A commonly-advanced answer is that the Japanese military administrations of South-East Asia were governed by an overly-narrow pragmatism, a simple or simplistic dedication to prosecuting the war quickly, using whatever and whomever was most concretely at hand. The dynamic of the Axis governments, after all, even at their centres, was decisive ‘action’ without hesitation, or hence much attention to long-range planning. This was particularly true of Japan's military-dominated government of 1941, which took South-East Asia without adequately determining how its oil was to be shipped to the distant North, let alone how its diverse peoples were to be engaged, ordered, inspired, or governed.

Accounts that treat the Japanese occupiers as ‘p...

Table of contents

- Front cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Notes on Contributors

- Prologue

- Japan and South-East Asia

- Burma/Myanmar

- Indonesia

- Malaya

- Borneo

- Thailand

- Philippines

- Maps

- Index