eBook - ePub

Sorcerers of Dobu

The social anthropology of the Dobu Islanders of the Western Pacific

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Ever since its first publication in 1932, Sorcerers of Dobu has been recognized as one of the great triumphs of anthropological research and interpretation in the field of ethnography. A rich source of information on primitive psychology, the book presents sociological analysis of the complex tribal organisation of the Dobuans.

Originally published in 1932

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sorcerers of Dobu by R. F. Fortune in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I

Social Organization

I

OUTLINE OF SOCIAL ORGANIZATION

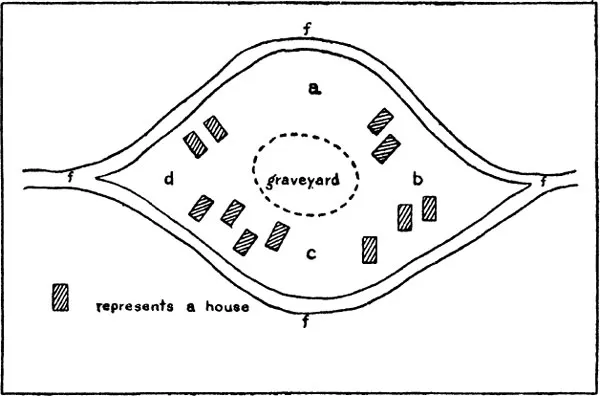

The ideal village of Dobu is a circle of huts facing inward to a central, often elevated mound, which is the village graveyard.

Fig I Villaǵe plan

In point of fact there are usually gaps in the circle of huts as at a, b, c, and d. These gaps represent old house sites of extinct family lines. A path, f, goes around the village behind the backs of the houses. This is for the use of passers by, who are not allowed to enter the village unless they are closely related to its members, or unless they have legitimate business of moment to transact.

In the centre of the village a clear space lies open with only scattered brilliant leaved croton shrubs upon it. Here below the sod within their stone set circular enclosure lie the mothers, and mothers’ brothers, the grandmothers on the distaff side and their brothers, and so, for many a generation back, the ancestors of the villagers on the distaff side. From the dead who lie in the central space individual ownership vested in soil and palm has come to the living. On the paternal side the ancestors of the village owners lie utterly dispersed in the villages of many stranger clans, the villages of their respective mothers and female ancestors.

In the following discussion I use the term villager in the restricted meaning of owner of village land and village trees. This use excludes those who have married into the village and who claim residence only through their spouses.

Each villager, male or female, owns a house site and a house. A woman inherits her house site from her mother, or from her mother’s sister. The husband in every marriage must come from another village than that of his wife. His house site is in one village, his wife’s house site is in another. A man’s son cannot inherit the house site of his father in his father’s village. After his father’s death he must scrupulously avoid so much as entering his father’s village. His father bequeaths his house site to his own sister’s son. His own son inherits house site and village status from his mother’s brother in his mother’s village.

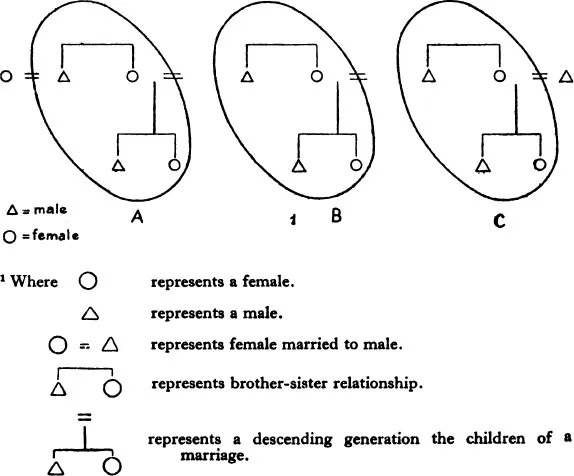

For the purpose of diagrammatic representation we may represent the village as one of its constituent units only.

We may represent the Dobuan situation graphically as below:—

Fig II

The oval enclosing lines mark off villages A, B, and C. For brother and sister own house sites in the same village, and children inherit house sites in their mother’s village, not possibly in their father’s. Hence a man, his sister and his sister’s children are the owners or potential owners of all village house site land.

Where a man’s house land is inherited there is he buried, in the central place adjoining the outer ring of house land. Thus no father is ever buried in the place of his children. A, B, and C represent a legal unit which keeps village land and the disposal of the corpses of its members strictly within itself.

The unit I have ringed about, of a man, his sister, and his sister’s children, is called in Dobuan the susu. It extends down the generations so that it may include a man, his sister, his sister’s children, and his sister’s daughter’s children, but not his sister’s son’s children, and so on. The children of any male member of the susu go out of it. In the above diagram I have represented each susu as a separate village in order to represent marriage out of the village. In reality, each village is a small number of susu, from four or five to ten or twelve, all claiming a common female ancestress and unbroken descent from her through females only. In practice only some of the number of susu can demonstrate this claim of common ancestry in their short known genealogies. But the claim is probably well founded, although not fully substantiated except by mythological validation in a mythical common ancestress.

All virtue in this system comes from descent through the mother. Every woman claims by right the inheritance of her brother for her male children. Hence this grouping is called susu, the term for mother’s milk. A husband beating his wife falls out with her mother’s brother, or with her brother whose inheritance she claims for her children. Her children are independent of her husband for legal endowment—they must by law be independent, and differently endowed. She is greatly independent of her husband, and only bound if he cares to indulge, as often happens, in suicidal self pity, and does not succeed in killing himself. Nevertheless, the suicidal resort is taken in a minority of cases; divorce is possible in the majority. It has become popular now for offended men to embark for work in the white man’s centres, rather than to attempt suicide, the more so since the old point of suicide, forcing one’s kin to avenge one on one’s cruel wife’s kindred, is difficult now owing to the white man’s laws against murder being fairly well enforced Nevertheless, despite the new fashion, the old way still persists side by sidè with the new.

If we come upon the village in its everyday aspect, when all is quiet, all its marriages going smoothly, it gives little apparent evidence of the strength of the susu. The susu does not live in a house. A man lives with his wife and children, and the interior of their house is strictly forbidden to anyone else, except at night to a lover of the daughter of the house. The man’s sister or the woman’s brother, or any other visitor, cannot ascend into the house but must rest under its elevated floor on the sheltered ground beneath, or, in the case of two men who are friends meeting, they may sit together on the elevated platform in front of the house, a small roof-sheltered “verandah”.

The susu has no common house for its exclusive use. Its only exclusive communal resting place is the graveyard, the centre ring with its red croton plants upon it; each hut of the many that surround the communal place of the susu shelters a biological family, the marital grouping as I shall term it throughout this account.

Normally the house interior is as rigidly restricted to man, wife, and their children, as the graveyard that the house fronts is rigidly restricted to the corpses of brothers, sisters, and sisters’ children, it being understood that the house is restricted to the one unit, the biological family only, whereas the graveyard is common to all the susu of the village. But in case of serious illness the patient is always removed on a litter to his or her own village, village of the mother, if residence at the time of sickness is otherwhere. Then, and then only, entrance to the house is possible to the matrilineal kin of the patient despite the presence of the patient’s spouse in the house. If serious illness turns to death the dead’s spouse is immediately prohibited from the house and the village of death. Within the house the near matrilineal kin mourn their dead. The alignment of kin within the house is, for the first and only time, the same as the alignment of kin within the graveyard. The house has ceased to be a house in its normal function. It is deserted for a season then destroyed.

Each marital grouping possesses two house sites, each site with a house built upon it. The woman has her house in her village, the man has his house in his village. The couple with their children live alternately in the woman’s house in the village of the woman’s matrilineal kin, and in the man’s house in the village of the man’s matrilineal kin. The change in residence usually takes place each gardening year, so that the one spouse spends alternate years in the other’s place and alternate years in own place; but some couples move more frequently to and fro. It is thus required that every person spend at least every alternate year, he with his sister and mother, she with her brother and mother (and, of course, mother’s brothers and sisters). Since every family grouping moves in this fashion, it follows that when a man is in his village his wife is also there, if his mother is in her village his father or his stepfather is also there, and if his sister is in her village his sister’s husband is also there. His mother’s brother may also be at home. Then his mother’s brother’s wife will be there. He and his sister, his mother with her sisters and brothers are all owners of the village land where they are resident, owners of the houses built upon it, and owners of the palms growing about the village.

They are the susu. His wife, his father, his sister’s husband, his mother’s brother’s wife, on the other hand, own land, houses, and palms in their own different villages. They are representatives of the various susu of other places, and they are in the place of their affinal relatives temporarily for the year.

Now, although these incoming visitors, who are not local owners, have each a retiring place in the village exclusively to themselves with their respective husbands or wives—the interior of the house—they spend a great part of the day and the early evening outside their houses in sight of and in frequent communication with the local owners and the wives and husbands of others of the local owners. Certain rules and observances govern this communication.

The incomers are called Those-resulting-from-marriage, or strangers, as a collective class by the collective class which is called Owners of the Village. Owners of the village use personal names between themselves freely to persons of their own or a younger generation. To their elders they prefer to use relationship terms, though the personal name is not forbidden. But Those-resulting-from-marriage cannot use the personal name of any one of the owners down to the smallest child, except in the case of a father to his own child. They must use a term of relationship. Owners of an ascendant generation can and do use their names freely, however. Moreover, one of Those-resulting-from-marriage cannot use the personal name of any other person in the same class. Again, a relationship term must be used. Those-resulting-from-marriage, while they are yet newly married, must approach an owner’s family sitting beneath the owner’s house by a roundabout way, circling in unobtrusively and bending apologetically while they do so—their own spouse being the only owner excepted. By the time one or two children are born this behaviour is usually discarded towards the own mother-in-law’s susu. But it remains even later towards other susu in the village (at least when an unusual mode of behaviour is set up, as when I might ask a man to come and introduce me to some of the more distant village relatives of his own mother-in-law’s susu).

“Those-resulting-from-marriage” are not supposed to be themselves kinsmen. It happens sometimes that they are. But this develops from linked parallel marriages between the same two places which are strongly disapproved. “Those-resulting-from-marriage” are supposed to be on entirely formal terms with each other when they are resident in the owners’ village, avoiding each other’s personal names. It is not fitting that they should be kinsmen and of the one village; and economic arrangements, as we shall see later, discriminate against such linked marriages. Moreover, in case two villages are linked by several marriages, as they are becoming nowadays in places where the population has receded seriously, a suicidal ending to one marriage might rend the others into two opposing groups bound to revenge and defence against revenge respectively. In the state of uneasy marriage found in Dobu it is fitting that one village should hesitate to involve itself over deeply with another, but prefer to spread its marriages widely. This is actually stated as the ideal.

“Those-resulting-from-marriage,” if they are men, are always abnormally uneasy about their wives’ fidelity. Now when a woman is in her own village, she has her kin next door and only too ready to eject her husband if he dares to lift a hand against her, or use foul language to her. She has no great dependence on her husband for care of her children, since a woman can nearly always get a new husband for future help, and her brother ultimately provides for them in any case. Consequently she behaves very much as she likes in secret. Suspicion and close watching are not relaxed by her jealous resultant-from-marriage. Sooner or later anger between man and wife flares up in public. Then the woman’s kin tell the man to get out. He has no sympathy from the others-resulting- from-marriage. They are for the most part no kin of his, and they are not a united body as the collective class formed of the several susu Owners of the Village are. The result is that the unfortunate resultant-from-marriage gets out precipitately, usually being designated in uncomplimentary obscene terms by irate owners as he goes. Dobuan folklore is full of husbands pathetically packing up their goods and going home to their mothers and sisters after a child has informed them that their wife has been consorting secretly with a male member of a distantly related susu of her own village. All men of the village call all women of the village of their own generation sister, but some are not close parallel cousins in reality, their relationship being of a degree that cannot be determined from known genealogy. Marriage within the village is strongly discountenanced, but casual sex affairs between distant “brothers” and “sisters” of other susu of the village occur often. The husband either gets out without insulting or striking his wife as in the folk-lore, or else both insults and strikes her and then gets out before he is injured, but under danger of injury, as I saw happen in real life. Conversely when a woman is in her husband’s place she is jealous of him and watches for signs of his intrigues with village “sisters” of his. I do not know how much actual village “incest” of this order there is, but I do know that suspicion of it is frequently flaring up into as much trouble as if the suspicion were perfectly founded. The offended husband always believes his suspicion is true, the owners invariably repudiate it, and no conciliatory mechanism exists, apart from the husband sometimes pocketing his pride later, sometimes not, and sometimes resorting to a suicidal attempt on his life. In reality, as in the legends, children are enlisted as informers. Jealousy normally runs so high in Dobu that a man watches his wife closely, carefully timing her absences when she goes to the bush for natural functions. And when it is the time for women’s work in the gardens here and there one sees a man with nothing to do but stand sentinel all day and play with the children if any want to play with him.

It will be apparent that the strength of the marital grouping is not improved by the solidarity of the susu, which is maintained by the rule of alternate residence. Incest prohibition is not too difficult to enforce within the small family. But when the children are grown adults, many with dead parents, belonging to different family lines that have only mythological validation of common ancestry, all thrust closely together by local residence and taught to regard their village mates as brothers and sisters, and people of other villages as dangerous sorcerers and witches, enemies all, then it is not unnatural that the strain of considering a woman of a friendly group as a sister sometimes breaks down. One’s wife, after all, is a member of a group that may only modify its underlying hostility at best. Parents-in- law are frequently divined by the diviner as the sorcerer or witch that is making one ill. In the lower social forms the bee’s division into three classes of queen, worker, and drone is a type that works with no strain. But sister-brother solidarity with an artificial extension of the sister-brother relationship does not work with the husband-wife solidarity very well unde...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- South Pacific and Australasia

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Introduction

- I Social Organization

- II The Garden

- III The Black Art

- IV The Spirits of the Dead

- V Economics

- VI Sex

- VII Dance and Song

- VIII Legend

- IX The Individual in the Social Pattern

- Appendix I: Dobu and Basima

- Appendix II Vada

- Appendix III Administration and Sorcery

- Appendix IV Heat and the Black Art

- Appendix V: Further Notes on the Black Art

- Appendix VI A Batch of Dance Songs

- Appendix VII Conclusion

- Index