- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Rautahi: The Maoris of New Zealand

About this book

A comprehensive study of the Maori in New Zealand, this book covers Maori history and culture, language and art and includes chapters on the following: · Basic concepts in Maori culture· Land· Kinship· Education· Association· Leadership & social control· The Marae· Hui· Maori and Pakeha· Maori spelling and pronunciationThere is an extensive glossary, bibliography and index.First published in 1967. This edition reprints the revised edition of 1976.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Rautahi: The Maoris of New Zealand by Joan Metge in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

chapter 1

The Maoris before 1800–I

Settlement and the development of Maori culture

The Maoris whom the European explorers found living in New Zealand in the late eighteenth century were easily identified, on physical and linguistic grounds, as Polynesians. Their oral traditions included accounts of an original homeland called Hawaiki and of ancient quarrels which precipitated a great migration by voyaging canoes southwards across the Pacific to New Zealand (Buck, 1949:4–73).

All tribes told the story of how Maui, the demi-god, fished the North Island of New Zealand out of the sea. Some attributed its rediscovery to Kupe, who circumnavigated it and sailed home, having seen only birds. Others gave the credit to Toi who, leading an expedition in search of a grandson lost at sea, landed in the Bay of Plenty, settled among the people he found living there and established a ruling aristocracy. Most tribes traced their dominion and prestige not to Kupe or Toi, but to ancestors who, they claimed, set out from Hawaiki on organized expeditions in sea-going canoes, carrying cultivated plants. Making landfall mostly in the Bay of Plenty, they settled in various parts of the country, assimilated the original inhabitants by marriage and conquest, and developed in subsequent generations into many independent tribes.

Early this century, a Pakeha scholar, Stephenson Percy Smith, fitted the varying tribal versions together in a scheme that brought Kupe to New Zealand in about ad 950, Toi in about 1150, and a final, dominant wave of immigrants in a ‘great fleet’ in about 1350. This scheme enjoyed a long popularity but has been discarded by scholars after re-examination of the traditions (Simmons, 1969a; Roberton, 1962).

Though even Maoris make shorthand reference to ‘the seven canoes of the great fleet’, the traditions use the word heke (migration) not ‘fleet’, and each tribe concentrates on the story of its own ancestral canoe. The names of eight canoes – Aotea, Arawa, Horouta, Kurahaupo, Mātaatua, Tainui, Tākitimu and Tokomaru – were familiar to most tribes, but there were many others of regional importance. Some canoes left together, met at points on the way, or made landfall about the same time and place, but none sailed the whole way together. Guarded use of the genealogies indicates that the captains of the famous eight canoes might have lived anywhere between 1200 and 1400. In 1956 Andrew Sharp attacked the idea of purposive two-way migration, maintaining that the canoes which reached New Zealand did so either by accident or by taking a long chance on discovering land to the south. He provoked a continuing controversy (Sharp, 1959,1963; Golson, 1972).

In recent decades, scientific study has greatly illumined our knowledge of Maori prehistory. Linguists have demonstrated that the language of the eighteenth-century Maori belonged to the same group as those of East Polynesia. Archaeologists have established that New Zealand was inhabited well before ad 1200, that its early inhabitants lived mainly by fishing and hunting moa (Dinornis) and other birds now extinct, and that their culture was unmistakably of East Polynesian provenance (Duff, 1956). The problem is to determine how this early culture, which archaeologists variously describe as Moahunter, Archaic Maori and New Zealand East Polynesian, was related to the ‘Classic Maori’ culture of the eighteenth century. Some scholars have suggested that the latter developed from the culture imported by the ‘fleet’. As yet, the archaeologists have found no evidence of the intrusion of a new cultural group (Golson, 1959; Groube, 1967).

Summarizing existing knowledge, Green (1974) suggested that the first arrivals brought an early form of East Polynesian culture and by adapting it to the New Zealand environment developed a New Zealand East Polynesian culture; that the bearers of this culture spread throughout the country, passing through at least two socio-economic phases, varying according to environment; that another distinctive culture then developed out of the earlier one in the northern part of the North Island as a result of adaptive innovations in isolation, influenced by the different environments from Polynesia and based on expandable food resources, especially of kūmara and fernroot; and that this ‘Maori culture’ also passed through several phases to a climax in Classic Maori and spread in certain of its regional aspects into southern areas, where it influenced or replaced later aspects of the New Zealand Polynesian culture.

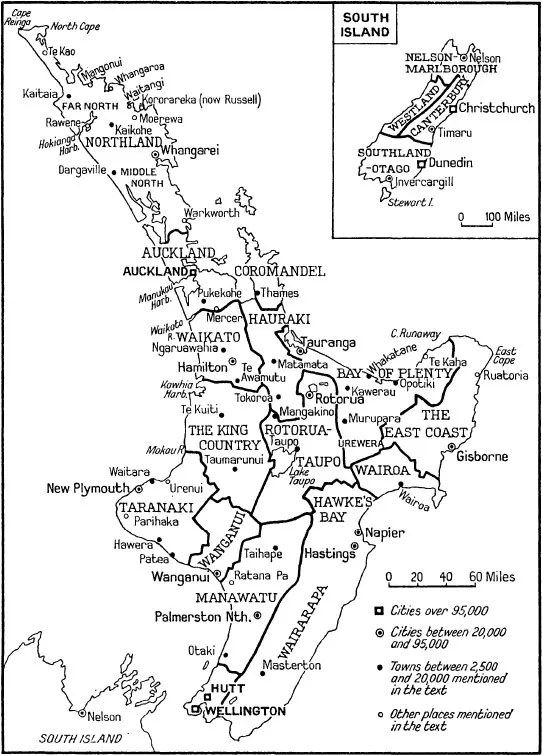

Figure 1 New Zealand 1975

The Maoris in the late eighteenth century

The standard works of reference on Maori society and culture at the time of the first European contacts are The Maori by Elsdon Best, which was first published in 1924, The Coming of the Maori by Peter Buck (1949), and Economics of the New Zealand Maori by Raymond Firth (1959). These writers made use whenever possible of direct, contemporaneous observations by the early explorers, but these were limited in quantity and scope. To fill in the picture, they drew largely on material collected later, especially between 1814 and 1850, on oral traditions written down after 1840, and on informants’ memories collected in the eighteen nineties, and even later. Projecting material back into the past in this way has problems which were not fully appreciated when these works were written. Many of the features they establish as typical of Classic Maori culture are mentioned rarely or not at all by early observers. On these grounds Groube recently advanced the thesis that ‘much of the change in Maori material culture which has been assumed to be prehistoric may in fact have taken place in the protohistoric period from the stimulus given to Maori culture by the arrival of European ideas and technology’ (1964: 17). In particular, he suggests that concentration in large villages, carved meeting-houses, storehouses on piles, and certain elaborated forms of carving, ornaments and decoration, were post-European developments. In this and the following chapter I have drawn mainly on the works of Buck and Firth to build up a picture of Maori society and culture in the late eighteenth century. While they undoubtedly need to be re-examined in the light of modern techniques and theory, I believe they stand up to the test remarkably well.

When Captain Cook sailed into New Zealand waters in 1769, the Maoris were a pre-literate, tribal people whose tools were mainly of stone, and whose economic and political organization was based on kinship. Cook estimated the population at 100,000. Up to 250,000 has been suggested, but estimates by archaeologists and a demographer agree on 110,000. Whatever their number, the Maoris were overwhelmingly concentrated in the north. Over four-fifths lived either to the north of the central uplands of the North Island or along the narrow coastal plains of Taranaki to the west and between Opotiki and Hawke’s Bay to the east (Green, 1974: 30–2).

Social structure

Iwi and waka

The free men and women who made up the majority of the population were divided into some fifty tribes (iwi), independent political units which occupied separate territories, endeavoured to settle internal disputes peacefully, and defended their political and territorial integrity by force of arms. The tribes varied in size from a few to many thousand members. In addition to tribal members, the population of each tribe’s territory included a few spouses belonging to other tribes, a number of slaves captured in war, and occasionally groups of refugees paying tribute as vassals. Each tribe was a descent-group in the broadest sense, membership being based on descent (or adoption by a descendant) from an ancestor identified as the tribe’s ‘founder’, traced through both male and female links. Most tribes were known by their founder’s name, prefixed by a word meaning ‘descendants of’: Ngāti, Āti-, Ngāi-, Aitanga-, Whānau- or Uri-. The rest bore names derived from an incident in their history.

The roster of tribes was not fixed: tribal histories make it clear that tribes waxed and waned. Sections of tribes (hapū) became tribes when large and powerful enough to enforce their right to independent action. Tribes weakened by war or famine were reabsorbed into related ones as sub-tribes. Whether a particular group was tribe or subtribe at any given time was often a matter for debate.

Tribes deriving from ancestors who came to New Zealand in the same canoe formed a waka (canoe), a loose association rather than a federation for defined ends. They recognized some obligation to help each other if asked, but frequently fought each other. The most important waka were: the Tainui tribes, whose territory stretched from Tamaki (where Auckland now stands) south to Mokau; the Arawa tribes of the Central Plateau; and the Mātaatua tribes of the Bay of Plenty. The tribes of the East Coast (between Cape Runaway and Wairoa) derived from Horouta and Nukutere, the Ngāti Kahungunu of Hawke’s Bay and Ngāi Tahu of the South Island from Tākitimu. In Northland and Taranaki, canoe traditions were diverse and relatively unimportant.

The hapū

The tribe was made up of a number of tribal sections called hapū, each of which controlled a defined stretch of tribal territory. Like the tribe, the hapū was a descent-group defined by descent from a founding ancestor through both male and female links and distinguished by his name. The ‘founders’ of all sections of a tribe and through them their members were linked by descent from the founder of the tribe. The hapū operated as a group on many more occasions than the tribe, especially with regard to land use, the production and use of capital assets such as large canoes and meeting-houses, and the entertaining of visitors. The large majority of a hapū’s members lived together on hapū territory, forming, with slaves and spouses from other groups, one or two local communities. In conversation and speech-making, the community was identified with the hapū and by its name. Thus though outside spouses never became members of the hapū descent-group, they were assimilated to it as an operational group and given rights of use in its resources as long as they lived on its territory. Members of a hapū who left its territory did not forfeit their membership. They could even pass on a claim to membership to their heirs. But they were not reckoned as part of its effective strength unless they returned.

Though the term is commonly translated as ‘sub-tribe’, hapū were often subdivisions of sub-tribes and even of sub-sub-tribes. When a hapū grew too large for effective functioning, some of its members broke away under the leadership of one of the chief’s sons or younger brothers and established themselves independently, either on part of the original territory or on land acquired by conquest or occupation, sooner or later acquiring a new name. Remembering their origin, minor hapū formed in this way often joined forces under the original name for large-scale undertakings.

The whānau

The basic social unit of Maori society was the household, which usually consisted of an extended-family: a patriarch (kaumātua) and his wife or wives, their unmarried children, some of their married children (usually the sons), and the latter’s spouses and children. Many also included slaves.

The free members of a household were described collectively as the whānau of its kaumātua. But whānau seems also to have been used to describe a kaumātua and his descendants, a bilateral descent-group including persons who were no longer members of his household, but excluding affines. This double use has caused a lot of confusion. Writers speak of iwi being divided into hapū, and hapū into whānau – and then proceed to define whānau as ‘the extended-family household’. We may speak of a hapū being divided into whānau only if we define the latter as a descent-group.

Descent-group affiliation

In most societies organized on the basis of descent, descent-group membership is obtained by affiliation through one kind of parent only, either the father (patrilateral affiliation) or the mother (matrilateral), and each descent-group consists of members attached through a line of links of one sex, either males (a patrilineal group) or females (a matrilineal group). But Maoris could attach themselves to any one descent-group through either parent and to different descent-groups of the same order through both parents at once (ambilateral affiliation). As a result, Maori descent-groups were composed of persons who traced their descent back to the founding ancestor through a line of mixed male and female links (ambilineal groups), and there was some overlapping in the membership of groups of the same order. Since marriage between tribes and hapū was the exception rather than the rule, this was of significance mainly at the whānau level (Firth, 1957,1963; Scheffler, 1964).

If a Maori’s parents belonged to the same descent-group at any level, he had a double qualification for membership, though usually he stressed that through the parent of higher rank. If they belonged to different groups he had claims to membership in each one.

But a claim to membership was only a claim until it was validated by contact with the group and participation in its activities. To obtain the full benefits of membership in a descent-group, it was necessary to live on its territory in close association with other members. If this were not possible, the rights accorded the claimant diminished in proportion to the frequency and length of his visits. A Maori normally gave primary allegiance to one group by living with it, while maintaining secondary ties with one or two others. He could change priorities by changing his residence. Unvalidated claims could be passed on for three or four generations, but were eventually extinguished if not taken up.

In affiliation as in other respects, Maori society preferred the male before the female. Young married couples usually lived with the husband’s parents, so that most children were brought up and identified themselves with their fa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Plates

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Introduction

- 1. The Maoris before 1800—I

- 2. The Maoris before 1800—II

- 3. The years between

- 4. Maoris and Maori culture today

- 5. Basic concepts in Maori culture

- 6. The bases of daily living

- 7. Language

- 8. Land

- 9. Kinship

- 10. Descent and descent-groups

- 11. Marriage and family

- 12. Education

- 13. Association

- 14. Leadership and social control

- 15. The Marae

- 16. Hui

- 17. Literature and art

- 18. Maori and Pakeha

- Appendix: Maori spelling and pronunciation

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index