![]()

1 Introductory

After many years of debate, acrid at times, and although the area itself has risen to a position of major world significance, the term ‘Middle East’ still cannot command universal acceptance in a single strict sense – even counting in ‘Mideast’ as a mere abridgement. Perhaps the most that a geographer can say, taking refuge in semantics, is that it can be regarded as a ‘conventional’ regional term of general convenience, like Central Europe or the American Middle West, with many definitions in more detail feasible and logically possible.1

Use of ‘Middle East’ first arose in the early years of the present century particularly with reference to the area around the Persian Gulf: it was then a logical intermediate definition between the Mediterranean ‘Near East’, and a ‘Far East’ – although the position of the Indian subcontinent remained anomalous – and after 1918 it was taken up by the British Forces as a convenient label. During the Second World War, bases and organizations previously located mainly around the Persian Gulf were expanded greatly; and rather than erect an indeterminate, and divisive, second unit, the term ‘Middle East’ was gradually extended westwards with the tides of war. A military province stretching from Iran to Tripolitania was created and named ‘Middle East’. Establishment in this region of large military supply bases brought the necessity to reorganize both the political and economic life of the countries concerned, in order to meet the changed conditions of war. A resident Minister of State was appointed to deal with political matters, and an economic organization, the Middle East Supply Centre, originally British but later Anglo-American, was set up to handle economic questions. It was inevitable that the territorial designation already adopted by the military authorities should continue in the new sphere; hence ‘Middle East’ took on full official sanction and became the standard term of reference, exclusively used in the numerous governmental publications summarizing political events, territorial surveys and schemes of economic development. It has even been suggested as a possible explanation that France had strong military claims in an official ‘Near East’ theatre of war, but fewer in a ‘Middle East’, which was therefore much employed as a term and extended as a geographical concept when the situation of France vis-à-vis Britain became equivocal in 1940–41. Some colour is lent to this view in that, despite a deputation from the Royal Geographical Society in 1946 to protest, Mr Attlee’s government continued the practice initiated by Mr Churchill’s coalition, by which Egypt, Libya, Israel, Jordan and Syria are officially termed part of a Middle East.

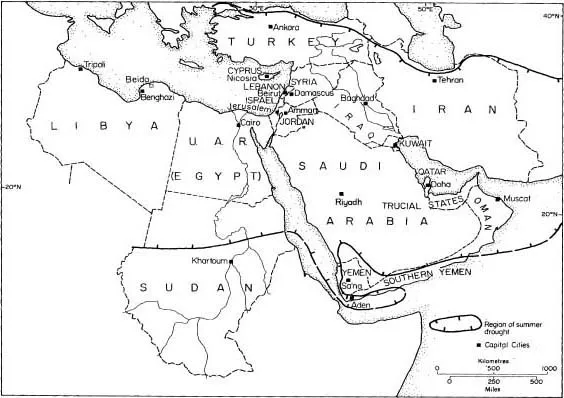

Fig. 1.1 The Middle East: countries and capital cities.

Under these circumstances, it would seem difficult to challenge the validity of ‘Middle East’, particularly as the general public in Britain and America has become accustomed to the usage – in some cases as the result of first-hand acquaintance with the region during military service. It is true that there is little logicality in applying the term ‘Middle East’ to countries of the eastern Mediterranean littoral; yet, as shown above ‘Near East’ – the only possible replacement – has an equally vague connotation; and to some, moreover, taken on a historical flavour associated with nineteenth-century events in Balkan Europe. Thus, despite the considerable geographical illogicality of ‘Middle East’, there is one compensation: in its wider meaning this term can be held to denote a single geographical region definable by a few dominating elements that confer strong physical and social unity.

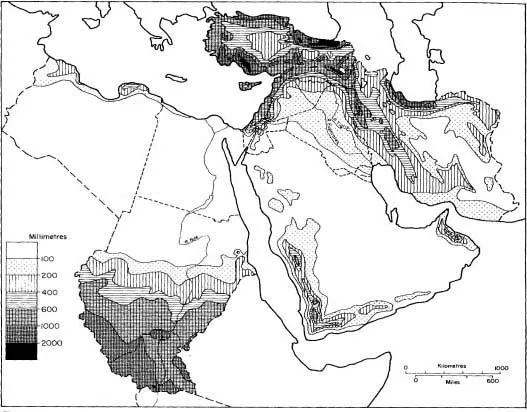

Within a territory delimitable as extending from Libya to Iran, and Turkey to the Sudan (including these four countries) it is possible to postulate on geographical grounds the existence of a natural region to which the name Middle East can be applied (fig. 1.1). The outstanding defining element is climatic: the Middle East has a highly unusual and characteristic regime which both sets it apart from its neighbours and also, since climate is a principal determinant in ways of life, the special climate induces highly distinctive and particular human responses and activities. It is true that this so-called unity is only partial, and therefore any definition of Middle East is open to criticism; but the common elements of natural environment and social organization are sufficiently recognizable and strong to justify treatment of the Middle East as one single unit. There are smaller intermediate areas on the margins: the southern Sudan in its physical and human geography is in certain respects closer to Central African conditions – though still part of the Nile Valley; extreme southern Arabia is brushed by monsoonal currents that give summer rain; whilst climatically and in much of its economic and social life Afghanistan has major affinities to a Middle East rather than to southern (monsoon) Asia. Thus, alternatives are possible: some modern geographers have written of a ‘South-West Asia’; and ‘Arab’ or ‘Moslem’ World are sometimes used, the former explicit within linguistic boundaries, the latter logically capable of extension to include parts of south-east Asia and central and east Africa. All definitions have some objective in logic; none is wholly clear and unambiguous, and personal idiosyncracy may be introduced to reinforce validity. Therefore, as was once said in this very region over territorial pretension, quod scripsi, scripsi.

Fig. 1.2 Middle East: annual rainfall.

Within this region, definable principally by its climate and its culture, there are however remarkable local variations in way of life and living standards, widened still further during the last 20 years by exploitation of petroleum. Although almost all communities in the region have experienced some absolute increase in income, either directly or by ‘spin off’ from outside, for a fortunate few this change has been enormous, producing for these few the highest per capita income of anywhere in the world. Within one locality or minor geographical region can now be found merchants, politicians and financiers deeply involved in international markets, whose views receive closest world-wide attention, together with political, religious and intellectual leaders also highly conscious of their status as members of world organizations. Yet there also exist alongside them in the same areas significantly large communities of farmers and herdsmen some of whom are still living, despite recent improvement, at near minimum levels of subsistence with personal incomes still below the World Bank criterion of ‘poverty’.

For long, complexity of geographical conditions – highly varied topography, prevalence of aridity with apparent absence of major economic resources, and consequent emptiness of many areas – retarded attempts at study. This was compounded by the reluctance of some indigenous communities, not unjustifiably, to admit outsiders; but above all by political rivalries and jealousies of outside powers, chiefly though not exclusively European, which were anxious to erect or preserve ‘spheres of influence’ particularly over routeways, and then as regards oil deposits. Now, however, with political independence, obstacles to investigation have greatly declined; and there is almost an opposite attitude – keen determination to understand the complexities and limits of the environmental endowment as a basis for technological and social development. There are now in a few areas situations approaching intensive investigation with a risk even of over-survey, since all results and recommendations cannot be implemented, in many cases due to shortages of trained personnel rather than money.

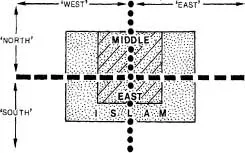

Fig. 1.3 The ‘Interface’ function of the Middle East.

Equally striking in recent times is the altered position of the Middle East in world affairs. Until the early twentieth century, and even later, south-west Asia and adjacent areas of Africa were largely isolated from the main currents of political and economic activity. Now, the region clearly ranks as one of the most significant parts of the world. Evidence of this could be adduced from the repeated personal visits by the Presidents of the USA and USSR, by the leaders of European opinion, and even by the Pope. Whilst some observers might dissent from the view of the Middle East as crucial in strategic matters, this is not true of the majority, and proof is to be seen in the fact that few major powers in the world can avoid having a ‘Middle East’ policy. Based primarily on reserves of petroleum, the largest in the world, and of natural gas, second largest after the USSR, certain Middle Eastern states have developed a level of industrialization and a financial strength that is now demonstrated by Middle East investment elsewhere in the industrial world: it is a long way in economic outlook, though certainly not in time, from the economic and political subservience of the 1930s and 40s to Arab and Iranian purchases of stocks and real property in Europe and North America: participation by Kuwait in London property, by Libya in Fiat and by Iran in Krupps and Daimler-Benz. The largest oil refinery plant, the largest petroleum export, gas refrigeration plant, the largest tankers, the most urbanized state and the best state medicine services in the world are now features in the Middle East, which also represents one of the best markets for sophisticated manufactures – most of all, armaments – outside Europe and North America.

Principally, however, the Middle East can now be regarded as a major interface area not only between East and West, which has long been its traditional role, but now between the newer alignment of ‘north’ and ‘south’ or in other terms, ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ nations. This latter role is increasing in significance with the Middle East more and more a consciously intermediate zone (fig. 1.3). Healthier in a few parts now than anywhere else in the world, with, for a minority, superb social services; a highly important market for some of the most sophisticated products of the industrial ‘northern’ world; and a respected mediator in world financial affairs, the Middle East has rapidly developed a new role. Yet at the same time, poverty of the majority, and geographical connection with Africa and Asia give the Middle Eastern peoples conscious affinity, economic, philosophical and political with the ‘southern’ world. Whilst the economic strength of OPEC since 1973 has been a major factor in world affairs, this has tended to reinforce intense interest by outside powers in Middle Eastern affairs, with sustained attempts to gain or retain political, economic and strategic advantages by possession of bases (now usually leased), trade links, and a patron–client relationship. Open dominance through Mandates has disappeared, but economic imperialism in the form of special trade relationships and ‘tied aid’ could be said to persist; and with the tense internal political situations recently described in 1977 by President Nimeiri of the Sudan as competing economic and armament imperialisms – Western and socialistic – the Middle East has significance much beyond its actual size or even numbers of population. Of recent years we have seen how the countries forming the Middle East have tended to be forced into the position of association with one or other of the major power blocs of the world. One or two Middle Eastern leaders, notably the rulers of Iran and Saudi Arabia, see their way to a vigorous national policy of independence, but for most others, support from outside, at least politically, is still necessary.

All this has produced a rapid change, amounting in some areas to crisis, in existing ways of life. Besides the pressures exerted on the natural environment by the spread of cities often on to the best agricultural land, the demand for water, increasingly polluted by human and industrial effluent, and the degradation of local ecosystems by various developments, there are urgent human problems. Forms of society that have endured over hundreds, even in some instances thousands of years are now in rapid decay, with urgent need for new groupings in replacement. Religious feeling, once the mainspring of most forms of cultural and political activity is now partly in eclipse, or subject (in an effort to restore it) to re-emphasis amounting in some instances to fanaticism or distortion: frequently materialist nationalism, sometimes dialectical, has taken its place, not always to advantage. Although new techniques of agriculture and industry have made considerable progress, ancient methods in husbandry, stock rearing and manufacturing still survive, so that for some communities the margin of existence is still extremely small, and living standards low. There has been enormous improvement since the 1940s, when it was possible to rank the Middle East as one of the worst nourished parts of the world; but changes have been highly uneven: in some regions very great; but in others slight. Population pressures are now a highly limiting factor, and for some countries, Egypt especially and possibly for Turkey, technological gains since 1940 have been largely nullified by extra human numbers to support. As well, given environmental limitations, one may be reaching the margin of effective utilisation of agricultural resources. Many Middle Eastern countries are experiencing the need for more and more food imports because increasing costs and decline of the rural labour force are placing limits on what can be produced from their own soil.

Change, amounting in some instances to disintegration, of internal society, and foreign pressures continuing from without, have increasingly forced Middle Eastern peoples to revise ideologies and adopt new ideas and techniques. In this connection one may note a situation special to the Middle East: close links between military elites and the ‘common people’ from whom many military leaders have come – there is a great deal of affinity between service officers and a new radical intelligentsia; with at the same time a strong nationalist feeling that can generate a negative attitude towards Communism. This means that the political and social paths open to Middle Eastern peoples may differ markedly from those so far shown by experience to be followed elsewhere: in short, the radical dialectic confidently predicted by some theorists as inevitably applicable to the West may not occur at all in the Middle East, or at least develop in a different form. Division and diversity, encouraged by factors of geography, may well continue for some time yet, as so often in the past, to dominate Middle Eastern affairs: and one essential step is to analyse how the geographical environment contributes to this situation. Only when we can be confidently aware of the real nature and influences of this environment will it be possible to formulate effective plans and policies.

1 C. S. Coon’s definition that includes Morocco and Pakistan, P. Loraine’s restriction of the term to Iran, Iraq, Arabia, Afghanistan; or the titles The Nearer East (D. G. Hogarth), The Hither East (A. Kohn), and Swasia (G. B. Cressey).

![]()

Part I

Physical geography of the Middle East

![]()

2 Structure and land forms

Though some doubts and uncertainties remain as to regional detail (and the commercial importance of oil-bearing strata has tended to retard complete public statements), knowledge of the geology and pattern of structural units is now much clearer. The situation of several decades ago, when one could note a near absence of published information for certain areas has now totally changed, as a result of the intensive surveys carried out for petroleum and other mineral exploitation.

Interest in the economic aspects of geological conditions tended to relegate the more theoretical questions of origins to a secondary role. This situation, however, has also improved in recent years, particularly following elaboration of the theory of plate tectonics, which has special applicability to the Middle East. We must therefore consider this theory in broad outline, with the reservation that much still remains to be worked out in detail for the Middle East, and ideas as so far stated are tentative and highly speculative.

It is apparent that whilst in some parts of the Middle East earth tremors and recent current volcanic activity are frequent, there is little or no trace in other parts of earth movement or volcanicity on any important scale. When the distribution of earthquakes, in particular, is plotted it becomes apparent that these occur within relatively narrow constricted bands surrounding much larger zones where disturbance is much less, or absent: i.e. large stable ‘plate’ areas with narrow boundary zones to which crustal disturbance is chiefly confined (fig. 2.1).

With this basis, elaborated by geo-magnetic observations and close observation of rock successions in relation to their origins, whether terrestrial, from oceanic deeps or otherwise, the theory of plate tectonics has been recently developed. Carrying further the earlier theories of Continental Drift, it postulates that the continental land areas are masses of less dens...