eBook - ePub

International Perspectives on Lifelong Learning

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

International Perspectives on Lifelong Learning

About this book

Taking an international perspective, the authors examine the theoretical and practical aspects of lifelong learning. A number of issues and key areas of debate are addressed in different national and international contexts and case studies are provided from countries including Hong Kong.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access International Perspectives on Lifelong Learning by Colin Griffin, John Holford, Peter Jarvis, Colin Griffin,John Holford,Peter Jarvis,Colin (Senior Lecturer in Adult Education Griffin,John (Senior Lecturer in Adult Education Holford,Peter (Head of Adult Education Jarvis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

INTERNATIONAL POLICY

Chapter 1

Edgar Faure After 25 Years: Down But Not Out

Roger Boshier

Going out with strangers

Go to the annual meeting of shareholders in just about any multinational corporation, settle into a soft seat in the rented hotel ballroom and, before too long, the smiling assistant will hand you the annual report. But, what’s this, profit and dividends are on the back pages? Instead of such mundane matters, the front pages trumpet the virtues of lifelong learning. Some companies even disguise their business. Instead of being a bank they’re a ‘learning organization’.

Everyone has heard the story. Being a learning organization or engaging in lifelong learning is now essential to economic health. It enables organizations to compete in the global economy. Moreover, by properly deploying technology such as the worldwide web, individuals can all be linked into learning networks. Now everyone has access to education without having to endure the indignities of admissions procedures, let alone authoritarian and disciplinary teachers.

The adult educators who helped UNESCO and others build an architecture for lifelong education must be delighted. Their ideas have moved out of church basements, extension offices, institutes of adult education and community groups and into corporate boardrooms. As this book demonstrates, there is considerable enthusiasm for lifelong learning which, in its most exaggerated or Utopian elaborations, is touted as the New Jerusalem which leads to a bountiful and promised land.

Much discussion around lifelong learning is infused with uncritical and utopic notions such as these. There is another side to this story and, in this opening chapter, the task is to examine the roots of lifelong education in the Faure (1972) Report and disentangle the threads of lifelong learning. At the centre of this analysis is the notion that lifelong education, as envisaged by Faure, is an entirely different creature to the one parading through corporate boardrooms dressed up as lifelong learning. For Gustavsson (1997) contemporary European notions of lifelong learning are a disguise for recurrent education. In our view, lifelong learning is recurrent education or human resource development (HRD) in drag. It might look splashy and alluring, it can preen and prance and strut its stuff. And it goes out at night. But what you see is not necessarily what you get. Remember what your mother said about going out with strangers?

Interests served

Learning To Be (Faure, 1972) the UNESCO report that proposed lifelong education as a master concept, was a response to the ferment of the 1960s. Constructed as a blueprint for educational reform in industrialized and so-called developing countries, it was launched on a wave of protest spawned by student activists, grave concerns about ecological catastrophe, crisis in French education and politics and the toxic remnants of the Vietnam war. At the time there were provocative critiques of formal education by innovative thinkers like Ivan Illich, John Holt, Everett Reimer, Paul Goodman, Paulo Freire and others whose work was nested in Anarchistic-Utopian or neo-Marxian perspectives (see Boshier 1994, Paulston 1977,1996) .

But now, 26 years after Faure, education is being transformed by neo-liberalism and architects of the new right have hijacked some of the language and concepts used while ignoring actions proposed by Faure. UNESCO deployed the notion of lifelong education as an instrument for developing civil society and democracy. In some ways the Faure Report echoed the British Ministry of Reconstruction 1919 Report, also billed as a ‘design for democracy’ (Waller 1956) .

The OECD, which earlier made Herculean attempts to erect an architecture for recurrent education, now proposes lifelong learning (not education) as the strategy for the 21st century. The European Union has also co-opted lifelong learning into a neo-liberal way of thinking where it is an instrument to enhance economic effectiveness. Hence, the first sentence of the European Union (1993) White Paper that led to the Year of Lifelong Learning asked ‘Why this White Paper?’ The answer – The one and only reason is unemployment. We are aware of its scale, and of its consequences too. The difficult thing, as experience has taught us, is knowing how to tackle it’ (1993: 1) . If lifelong education was an instrument for democracy, lifelong learning is almost entirely preoccupied with the cash register.

Roadside mugging

The central point of this chapter is that Faure was mugged on the road to the 21st century. Bruised and abused by architects of the new right, Faure’s language is in use but the emancipatory potential of the report is wounded. Worse still, this was not an isolated mugging or sneak ambush on a dark road. Everywhere Faure’s concepts and language have been stolen by advocates of a form of globalization which has everything to do with corporate élites and economics and, in stark contrast to what Faure was saying, appears untroubled by the erosion of civil society and democratic structures. At the centre of this analysis is the notion that, despite the advancing age of Faure’s commissioners and the tendency to dismiss their work as unduly Utopian and impractical, the original report is still an excellent template for educational reform. It is one of the outstanding adult education texts of the 20th century and, moreover, some of the surviving authors have not bent to the winds of globalization (Rahnema and Bawtree 1997) .

In an attempt to revive some of the Faure ethos, UNESCO recently commissioned another enquiry into the future of education. The Delors (1996) report, entitled Learning: The Treasure Within, rectified some of the imbalances in the Faure commission processes. For example, whereas all seven of the Faure commissioners were men, five of the fifteen Delors commissioners were women. But the ink was barely dry on the Delors book when the OECD, the European Union and several other national or international organizations issued their own reports on lifelong learning (eg DfEE 1995, Dohmen 1996, Tuckett 1997) .

Making the Faure Report

In December 1965 UNESCO’s International Committee for the Advancement of Adult Education received a paper from Paul Lengrand on continuing education and recommended that the organization endorse the notion of lifelong education. After the French riots of 1968 and the worldwide critique of higher education, René Maheu, Secretary-General of UNESCO, created an International Commission on the Development of Education. These days it would not be acceptable to ask seven men to undertake a worldwide enquiry into the state of education. However, despite the absence of women, Maheu attempted to secure commissioners who would represent contrasting cultural sets.

One of the Faure commissioners was Majid Rahnema, who had been a career ambassador for much of his life. In 1967 he was asked to form Iran’s first Ministry of Science and Higher Education. Later he founded an Institute for Endogenous Development inspired by the work of Paulo Freire and other advocates of bottom-up development As a cabinet minister he was vulnerable but left Iran before the revolutionary upheavals that led to the demise of the Shah After a period as a UNDP Representative in Mali René Maheu invited Rahnema to join the International Commission for the Development of Education At the time he was living in France and able to accompany Chairman Faure to Latin America and other places (Boshier 1983) .

Faure and Rahnema travelled to several countries, sometimes with other commissioners or members of the UNESCO secretariat. They received submissions from government sources and made special efforts to meet critics of education. As well, UNESCO commissioned papers from leading scholars, some of whom were staunch critics of formal education. Learning To Be was prepared at the UNESCO secretariat. Rahnema did more writing than others because he had more time than other Commission members. The Commissioners acted as individuals, not as representatives of their various governments.

Edgar Faure’s appointment to chair the commission was intriguing. Before his death in 1988 he occupied every important post in the French government except the Presidency. He was one of France’s most progressive Ministers of Education and, after the student revolts of 1968, masterminded sweeping reforms of higher education. Something of a renaissance man, he also wrote musical scores and detective novels. At the age of nineteen he had earned a doctoral degree. Later in life he had an old-fashioned sense of honour. Once, after having had his motives questioned in print by a magazine reporter, he challenged the writer to a duel. Notoriously near sighted, he was waving the pistol when a colleague talked him out of it. He was also something of a father figure and, in France, known affectionately as Edgar. Maheu’s decision to ask Faure to head the International Commission was most fortuitous.

Concepts

There is no doubt that 1972 was a halcyon year for educational reform and at about the time delegates met at the Tokyo conference on adult education, UNESCO released Learning To Be (Faure 1972) . 1972 was also the year of the influential UN Conference on the Environment, held in Stockholm, where delegates considered the Blueprint for Survival, assembled by the editors of the Ecologist (Goldsmith et al.1972) and the Club of Rome Report Limits to Growth (Meadows et al.1972) . It was also the year of the progressive Worth (1972) Report in Alberta, influenced by recurrent education (Kallen 1979) and the Wright (1972) Commission Report (in Ontario) on the need for a ‘learning society’ (Pawlikowski 1998) .

The architecture of the Faure Report was organized around three concepts, which concern the vertical integration, horizontal integration and democratization of education systems. A vertically and horizontally integrated and democratized system of education would result in what Faure called a learning society.

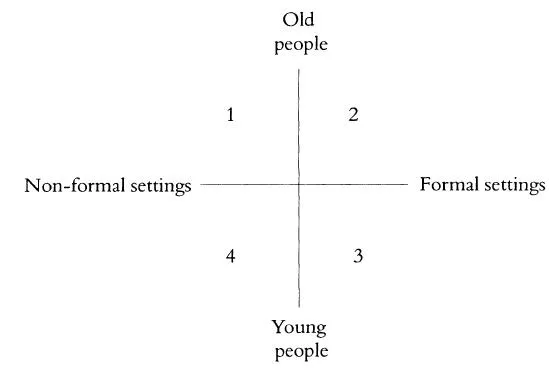

Figure 1.1 Dimensions of lifelong education

Figure 1.1 is our rendering of what the Faure commissioners were talking about. Extant educational systems assign an undue emphasis to the education of young people in formal settings (Quadrant 3) . In a learning society, there would be a more equal distribution of resources and emphasis on each quadrant. Hence, there would as much emphasis on the education of young people in non-formal (Quadrant 4) as in formal settings (Quadrant 3) . As well, there would be a considerable emphasis on the education of older people (adults) in formal (Quadrant 2) and non-formal settings (Quadrant 1) . Each quadrant is the same size as every other. This is because in a learning society there would be a more equal distribution of resources and emphasis on each quadrant. Hence, there would as much emphasis on the education of young people in non-formal (Quadrant 4) as in formal settings (Quadrant 3) . As well, there would be a considerable emphasis on the education of older people (adults) in formal (Quadrant 2) and non-formal settings (Quadrant 1) . Each quadrant is the same size as every other. This is because in a learning societythere would be a more or less equal amount of emphasis on education in each of the four quadrants. Moreover, although the vertical and horizontal lines in Figure 1.1 look solid, in a learning society they would be permeable. A child or adult learner would be able to swim back and forth, much like a fish, securing education in a formal setting today and a non-formal one tomorrow. The emphasis would not be on where a learner gets educated. Rather, the focus would be on the quality of what is learnt. As well, there would be a more relaxed attitude about prerequisites. Systems or, as Rahnema prefers to say, unsystems, would accept that learning does not always occur in linear ways and learners could secure access to higher levels without always having done the so-called prerequisites (Boshier 1983) .

Learning and education

In parts of this book and in many places around the world, learning and education are used interchangeably. This can be a source of confusion. The notion of lifelong learning has little theoretical juice since learning (as an internal change in behaviour) is an inevitable corollary of life. Some advocates of lifelong learning specifically reject the use of ‘learning’ to label a psychological construct and, instead, use it as a gerund to describe an array of behaviours that sound very much like education. For example, Tough’s (1971) adult learning projects have precisely the kind of deliberate and systematic qualities normally associated with education. It is, however, easy to understand the motivation of those wanting to promote learning. In the public mind, education is so indelibly identified with schooling that it becomes necessary to invoke a term that doesn’t trigger all the bad thoughts about school. Having barely survived teacher incompetence and the brutality of Hastings Boys’ High School in New Zealand the author understands why some people want to use learning to distance it from schooling.

But practitioners should be wary because lifelong learning denotes a less emancipatory and more oppressive set of relationships than does lifelong education. Lifelong learning discourses render social conditions (and inequality) invisible. Predatory capitalism is unproblematized. Lifelong learning tends to be nested in an ideology of vocationalism. Learning is for acquiring skills that will enable the learner to worker harder, faster and smarter and, as such, enable their employer to better compete in the global economy. These days, lifelong learning often denotes the unproblematized notion of the savvy individual consumer surfing the Internet (Boshier et al.1997, Boshier, Wilson and Qayyum 1997) .

Education is the optimal (and usually systematic) arrangement of external conditions that foster learning. Education is a provided service. Lifelong education requires that someone – often government or other agencies –develop policys and devotes resources to education that will preferably occur in a broad array of informal, non-formal and formal settings. Deliberate choices must be made. Hence, whereas lifelong learning is nested in a notion of the autonomous free-floating individual learner as consumer, lifelong education requires public policy and deliberate action. Lifelong learning is a way of abdicating responsibility, of avoiding hard choices by putting learning on the open market. If the learner as ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- The Contributors and Editors

- PART I INTERNATIONAL POLICY

- PART II LIFELONG LEARNING IN THE LEARNING SOCIETY

- PART III LIFELONG LEARNING AND POLITICAL TRANSITIONS

- PART IV LEARNING, MARKETS AND CHANGE IN WELFARE STATES

- PART V LEARNING AND CHANGE IN EDUCATIONAL STRUCTURE

- PART VI LEARNING AND CHANGE AT WORK

- PART VII AIMS, ETHICS AND SOCIAL PURPOSE IN LIFELONG LEARNING

- Index