![]()

Part I

Introductory context

![]()

1 Sustainable culinary systems

An introduction

Stefan Gössling and C. Michael Hall

Eating, more than any other single experience, brings us into a full relationship with the natural world. This act itself calls forth the full embodiment of our senses – taste, smell, touch, hearing and sight. We know nature largely by the various ways we consume it. Eating establishes the most primordial of all human bonds with the environment … [it] is the bridge that connects culture with nature.…

(Rifkin 1992: 234)

Introduction

In April 2012, German newspapers reported that discounter Aldi, one of the largest retail chains in the world, had reduced the price of standard milk by almost 15 per cent to €0.48 per litre, and to €0.42 per litre for low fat milk (Spiegel 2012). German farmers protested, as in previous years, when the price of milk had been reduced by the discounter, and the spokesperson for agriculture of the Green Party suggested that ‘consumers don’t want [price-]dumped milk’ (Stern 2012). As a reaction to the national news, Badische Zeitung, a regional newspaper with a specific children’s page, unexcitedly informed its young readers that cows are now producing amounts of milk several orders of magnitude more than in historical times, while their life expectancy has – because of the strain of intensive milk production – massively declined. In the EU15, average per cow milk production is now 6,709 kg per year, reaching its highest level of 8,569 kg per cow per year in Denmark (EU 2012). This level has increased constantly since 2001, when the EU15 average was 5,998 kg per cow per year, with 7,070 kg per cow per year in Denmark, the EU’s leader in agro-engineering in this sector. Milk production has for a long time been moving towards industrialization, equivalent to the full-scale industrialization of chicken and pig rearing, and animal welfare is clearly not relevant in this trend. It thus remains doubtful whether price-conscious consumers care about the background of price-dumped products: it is in particular the ‘price aggressive retailers’ that have continued to grow rapidly, according to Planet Retail (2011).

The example illustrates one of the many frictions between consumer expectations, retail concentration and increasing demands on sustainability in today’s food production, with related sustainability implications including land conversion and the associated loss of biodiversity and ecosystems (Lawton and May 1995; Pimm et al. 1995; Vitousek et al. 1997a; Sage 2012); changes in global biogeochemical processes, such as nitrogen cycles (Vitousek et al. 1997b); water consumption (Chapagain and Hoekstra 2007, 2008; Hoekstra and Chapagain 2007); the use of substances potentially harmful to human health, such as pesticides, herbicides and fungicides (Koutros et al. 2008; Bhalli et al. 2009); and ethical questions, such as those relating to genetically modified organisms (Zollitsch et al. 2007). Another significant problem is the sector’s contribution to global emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs) from agriculture, food processing, storage, transport and the preparation of meals (Gössling et al. 2011) as well as the global contribution of processed foods to increasing levels of diet-related diseases and risk factors (cardiovascular, diabetes, obesity) (Hawkes 2008).

These issues will gain in importance in the future, as a growing world population and demand for high-protein food create pressure on farmers to produce increasing volumes of (protein-rich) food at declining unit costs. At the same time, oil prices, land availability and water competition are likely to make production more expensive, while extreme weather events related to climate change will increase the vulnerability of production, potentially aggravating the effects of biofuel production on agricultural lands (e.g. Royal Society 2008). Notably, there is now a rapid expansion of discounter chains from the developed countries in the emerging economies, leading to further concentration in the food sector. Of course, some will claim that the global commercial food and agriculture industry has actually contributed to a great food success story with respect to feeding the world. For example,

World population has doubled while the available calories per head increased by 25 percent. Worldwide, households now spend less income on their daily food than ever before, in the order of 10–15 percent in the OECD countries, as compared to over 40 percent in the middle of the last century. Even if many developing countries still spend much higher but declining percentages, the diversity, quality and safety of food have improved nearly universally and stand at a historic high.

(Fresco 2009: 379)

As Sage (2012: 2) observes, ‘we have arrived as a point where food has become a highly contested arena of competing paradigms’ (see also Lang and Heasman 2004). As a counterpoint to Fresco (2009), Sage (2012) notes a number of current shortcomings and weaknesses of the global agricultural and food system:

• Market mechanisms cannot ensure equitable access to food. An estimated one billion people around the world are experiencing hunger and malnutrition.

• The profit-seeking behaviour of food companies has encouraged the promotion of convenience, confectionary and snack products that are high in salt, sugar and fat. Over one billion people in the world are overweight or obese and susceptible to diet-related disease.

• The declining share of food in household budgets

does not reflect the true economic, social or environmental cost of its production, distribution and consumption. What we pay for food at the supermarket checkout does not take into account the loss of ecological services, the depletion of resources, the impairment of Earth system processes, and the rising medical costs of poorer human health.

(Sage 2012: 3)

• Questions of delivering global food security to an increasingly urbanized and growing global population will require new approaches to ensure appropriate developmental, environmental and social justice outcomes.

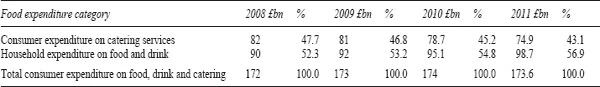

Virtually all of these issues have direct and indirect links to tourism and hospitality. Tourism is of relevance in food consumption because of the enormous amounts of food prepared in both leisure and business tourism contexts, including the food consumed in restaurants, cafeterias and canteen kitchens as well as on board trains, aircraft, ferries or cruise ships. According to one estimate, some 75 billion meals per year, or just over 200 million meals per day, might be consumed in tourism (Gössling et al. 2011). In a broader setting, the food service sector (also known as catering), which includes the businesses and institutions responsible for any meal prepared outside the home, is responsible for a very high proportion of food sales. In 2002 the value of global sales of food was estimated at US$4.096 trillion, of this US$1.803 trillion or a little over 44 per cent of total sales by value was in the service sector, with the remainder in retail (Gehlhar and Regmi 2005). According to Gehlhar and Regmi (2005: 5), ‘With consumers increasingly demanding convenience, it is likely that the value of global foodservice sales will overtake global retail food sales in the future.’ Data for the UK (Table 1.1) indicate that although the relative proportion of consumer expenditure on catering services declined between 2008 and 2011 as a result of the economic climate, it still accounted for over 43 per cent of total sales. In addition, the catering sector employed 1.415 million people compared to 1.139 million people working in food retail (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) 2011).

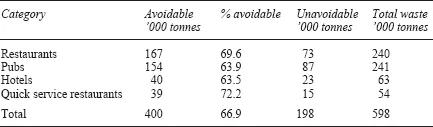

Consumption of food is associated with both production and waste. It is estimated that total UK food and drink waste is around 15 million tonnes per year, with households generating 7.2 million tonnes/year of which 4.4 million tonnes are avoidable (DEFRA 2011). In 2009 the UK hospitality sector disposed of around 600,000 tonnes of food waste to landfill, of which almost two-thirds was avoidable. It is estimated that UK hospitality businesses pay approximately £1.02 billion a year for food that is subsequently wasted (DEFRA 2011). However, levels of food and drink waste generated by the hotels and catering sector had dropped by over 40 per cent between 2002–3 and 2009 (DEFRA 2011) (Table 1.2 illustrates UK food hospitality waste going to landfill).

Table 1.1 Consumer expenditure on catering services in the UK as proportion of total food expenditure, 2008–11

Source: derived from DEFRA (2008, 2009, 2010, 2011).

Table 1.2 UK food hospitality waste going to landfill in 2009

Source: derived from DEFRA (2011).

Depending on the choices made by those responsible for purchases, this may increase or decrease the sustainability of the global food industry, in particular with regard to three issues. First, sustainability in food consumption is in the hands of a few decision makers. For instance, the initiative by hotel chain Scandic to purchase only organic and fairly traded coffee affects 20 million cups of coffee served per year (Scandic 2012). In contrast, the German railways company (Deutsche Bahn) sources its foodstuffs from all over the world, with chicken and beef being imported from South America. Second, food service establishments can potentially cook food more efficiently, as the simultaneous preparation of many meals typically entails lower energy use per meal (Carlsson-Kanyama et al. 2003). At the same time, restaurants may offer more complex and hence energy-intense food creations, also generating higher amounts of food waste (e.g. Swedish Environmental Protection Agency 2008). Third, food purchases have considerable influence on the globalization of the food industry. Evidence suggests, for instance, that purchasing strategies are generally characterized by a focus on the lowest per-unit costs, leading to growing pressure on food producers. This, in turn, encourages the industrialization of food production, which Vos (2000) argues has led to many of its current problems, including outbreaks of swine fever and bovine spongiform encephalopathy.

Over the longer term, tourism and hospitality also influence foodways, food value chains and distribution channels. Globalization not only affects contemporary foodways and food systems but also has an important historical context.

Single, local ecology food, is a peculiarly twenty-first-century construct. Sugar, the potato, the tomato, maize and many other ‘New World’ foods transformed the range and scope of culinary expression, but in distinct and uneven ways in different European food provisioning and culinary systems.

(Harvey et al. 2004: 202)

The globalization of some foods to the extent that they are integral to the cuisine of regions far away from their natural ecological range is testimony to the complexity of the interactions between agricultures, food consumption, trade and tourism as well as the development of food media (Mintz 1986; Zuckerman 1999; Hall and Mitchell 2000; Green et al. 2003; Harvey et al. 2003). As Probyn (1998: 161) commented, the global–local tension of localization is

compellingly problematized by food. Whether overly politicized or not, eating scrambles neat demarcations and points to the messy interconnections of the local and the global, the inside and the outside. Food systems (from production to consumption) highlight the singular and current ways in which the private is becoming public, and the public is being privatized.

This book does not focus on all these issues, but it aims to develop a range of related perspectives so as to initiate awareness and debate about the role of tourism and hospitality in the global food system and, ultimately, its sustainability. Firstly, food consumption is widely recognized to be an essential part of the tourism experience (Hjalager and Richards 2002; Boniface 2003; Hall et al. 2003; Hall and Sharples 2008). For instance, locally distinctive food can be important both as a tourism attraction in itself and in helping to shape the image of a destination (Hall et al. 2003; Cohen and Avieli 2004; du Rand and Heath 2006). Since the 1990s a number of articles have emphasized the potential for local food experiences to contribute to sustainable development, help maintain regional identities and support agricultural diversification, parti...