![]()

Gender balance/gender bias: the teaching profession and the impact of feminisation

Sheelagh Drudy

University College Dublin, Ireland

The teaching of young children has long been dominated by women. This global phenomenon is firmly rooted in issues relating to economic development, urbanisation, the position of women in society, cultural definitions of masculinity and the value of children and childcare. There have been expressions of concern by the media, by government ministers, and others, in a number of countries about the level of feminisation of the teaching profession. This paper focuses on this important issue. It reviews current research and critically analyses international patterns of gender variations in the teaching profession and considers why they occur. It gives particular consideration to a number of key questions that have arisen in debates on feminisation: Do boys need male teachers in order to achieve better? Do boys need male teachers as role models? Are female teachers less competent than male teachers? Does feminisation result in a reduction in the professional status of teaching?

Introduction

The teaching of young children has long been dominated by women. This global phenomenon is firmly rooted in issues relating to economic development, urbanisation, the position of women in society, cultural definitions of masculinity and the value of children and childcare (Drudy et al. 2005). There has been a proliferation of media scare stories and moral panics about the underachievement of boys. Indeed, there have been expressions of concern by government ministers in a number of countries (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) 2005; Skelton 2007). It has been argued that one way of capturing the changes under-way both in teaching and in the wider dimensions of Western societies is through the use of the concept of feminisation and an accompanying masculinity crisis (Haywood, Popoviciu, and Mac an Ghaill 2005). This paper reviews current research and critically analyses international patterns of gender variations in the teaching profession and considers why they occur. It gives particular consideration to a number of key questions that have arisen in debates on feminisation: Do boys need male teachers in order to achieve better? Do boys need male teachers as role models? Are female teachers less competent than male teachers? Does feminisation result in a reduction in the professional status of teaching?

Teaching is a highly feminised profession

Policy documents emanating from the OECD, and from the EU, acknowledge the fact that in most member countries the teaching profession is characterised by gender imbalances. Female predominance in school teaching is to be found in most countries throughout the world. In all European member states, and indeed in former Eastern bloc satellite states for which figures are available, women are in the majority at primary level and (to a lesser extent) at secondary level (see Table 1).

Table 1. Percentage of teachers who are female in selected countries.

| Countries | Percentage Teachers who are Female |

| Brazil*, Russian Federation, Italy, Slovakia, | Women more than 90% of primary teachers |

United States, United Kingdom, Ireland | Women more than 80% of primary teachers |

| China, Tunisia | Women between 49% and 54% of primary teachers |

United States*, Ireland*, United Kingdom* | Women between 56% and 59% of lower & upper secondary teachers |

| Canada* | Women 67% of lower & upper secondary teachers |

Finland*, Italy*, Czech Republic* | Women 71%, 73%, 81% of lower secondary teachers respectively, 57%, 59%, 56% of upper secondary teachers respectively |

| Korea*, Switzerland*, Germany*, Netherlands* | Women between 28% and 40% of upper secondary teachers |

Sources: Countries with asterisk* UNESCO 2003; others UNESCO 2008.

In some countries women are greatly in the majority, with the largest proportions found in Brazil, the Russian Federation, Italy and Slovakia. In only a few countries are the number of women and men in primary teaching approximately equal. Examples of these are China and Tunisia. However, globally, there are some variations – even in primary teaching which is the most feminised sector (see Table 2).

Figures from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) show that, while the proportion of women in primary teaching increased in all geographical regions worldwide in the latter part of the twentieth century (the period 1970–1997), in the least developed countries they remained in a minority (see Drudy et al. 2005, 163; UNESCO 2003). Indeed, although the figures in Table 2 mask variations between countries within the different regions, the proportions of women in teaching in the different regions worldwide could reasonably be taken as indicators of the stage of economic development in various regions (Drudy et al. 2005; UNESCO 2008).

At secondary level internationally, the percentage of women teachers is lower than at primary level. For example, in OECD countries the United States, the United Kingdom and Ireland, Italy, Canada, Finland and the Czech Republic have some of the highest proportions of women teachers in secondary schools. At the other end of the spectrum there are some countries with very low proportions of female teachers at secondary level. Exact comparisons are difficult as many countries combine their figures for primary and lower secondary and provide upper secondary separately, whereas others combine lower and upper secondary and provide primary figures separately. There are also slight variations according to the different compilations of databases (e.g. as between OECD and UNESCO figures, and sometimes even between different tables produced by each of these organisations). The proportions of women in upper secondary are particularly low in the following countries: the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland and Korea (UNESCO 2003). As for less developed countries, the proportion of women in secondary level teaching is even smaller than that in primary teaching (Drudy et al. 2005, 163).

Table 2. Females as a percentage of all primary teachers in the different world regions (Year 2005).

| World Region | Females as a Percentage of All Primary Teachers |

| East Asia and the Pacific | 59.5% |

Latin America and the Caribbean | 77.4% |

| North America and Western Europe | 84.4% |

South and West Asia | Data not available |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 45.3% |

Source: UNESCO 2008.

Why do so few men become teachers?

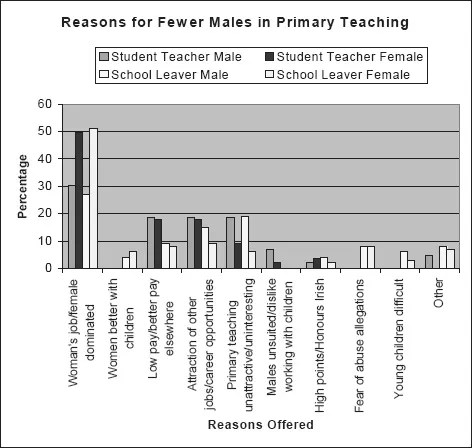

Perceptions of the low level of men choosing to be teachers were explored in a study of school students and student teachers carried out in Ireland by this author and colleagues (Drudy et al. 2005). Figure 1 presents the views of student teachers already undertaking initial teacher education courses for primary teaching, and final year school students, on why relatively few men choose teaching, in particular primary teaching.

The perception that primary teaching is a woman’s job, or that it relates to a mother’s role, was the most frequently offered explanation by both the school students and the student teachers for the low proportion of male entrants to primary teaching, with 42% of the school students and 45% of the student teachers offering this reason. However, these overall percentages masked very considerable gender differences. Females offered this reason much more frequently than males. The second most common reason given by both groups was the attraction of other careers. Again, there were marked gender differences here, as almost twice as many boys as girls suggested this. The third most commonly offered reason by school students was a perception of primary teaching as unattractive – as boring, hassle causing, stressful or requiring too much patience. ‘Low pay’ which is often given as the prime reason for fewer males in teaching came joint fourth for school students but was offered more frequently (and in joint second place) by student teachers. The reasons suggested for the dropping numbers of male primary teachers indicated a bias towards seeing the ideal primary teacher as female, based on an essentialist belief that a woman’s nature tends to make her better with children. This belief was stronger among males than among females, more of whom were convinced of the potential of both sexes to teach at primary level.

Figure 1. Reasons offered by school students and student teachers for the falling number of males entering primary teaching, by gender.

In this study there was a strongly perceived association among respondents between the nurturing role of women and their assumed greater suitability for teaching very young children. The domestic ideology which provides cultural support for the notion that women’s careers should be compatible with homemaking responsibilities, while weakening somewhat over the last couple of decades in Ireland and elsewhere, was still perceptible. It was evident in a number of ways in the findings in this study – e.g. in the perception of school students and, albeit to a lesser extent, student teachers, that women were best suited to the career of primary teaching. No such ideology existed to provide a connection between men’s careers and homemaking/parental responsibilities. Obviously, patterns of choice or lack of choice of teaching as a profession are linked to the social construction of masculinity and femininity. Research indicates that the feminisation of teaching is a cumulative historical and social process. The manner in which the feminisation of teaching has occurred involves subtle patterns of socialisation in Western cultures. In many Western societies there has been an ideological link between women’s domestic roles and their commitment to teaching. This ‘domestic ideology’ proposes that women are ‘naturally’ more disposed towards nurture than are men. Somewhat contradictorily, recent debates have focused on the assumed need for young male children – especially at primary school – to have male teachers as role models.

Do boys need male teachers in order to achieve better?

Concerns have been expressed that boys require male teachers if they are to develop properly both academically and personally. This expression of concern focuses in particular on perceived male underachievement in relation to their female counterparts. Recent research and public examination results in many countries have tended to confirm patterns of gender differences in academic achievement – i.e. on average, in the last decade and a half of the twentieth century in most of the developed world girls have performed better (OECD 2007, 43). Research has suggested that girls learn to read earlier, obtain higher grades and cooperate more with their teachers. However, in order to understand and address this appropriately, the need has been identified for more sophisticated and nuanced analysis of male and female achievement rates, incorporating factors such as social class, classroom interaction patterns, language competences and school settings, and different types of assessment (Epstein et al. 1998; Lynch 2000; Gorard, Rees, and Salisbury 1999; Elwood 1999; Jones and Myhill 2004). Considerable research has also shown that teachers need to be aware of their own patterns of interaction with male and female pupils and its impact on them (Hopf and Hatzichristou 1999; Cammack and Phillips 2002; Martino, Lingard, and Mills 2004; Jones and Myhill 2004; Nambissan 2005). The widespread findings of boys’ dominance of much of the classroom interaction during whole class teaching, and the fact that many teachers behave differently in their interactions with girls and boys suggest this is another intervening variable in patterns of achievement and that these research findings should be incorporated into teacher education programmes (Drudy and Uí Chatháin 2002; Younger, Warrington, and Williams 1999; Einarsson and Granström 2002; Tsouroufli 2002; Weaver-Hightower 2003; Gray and Leith 2004; Beaman, Wheldall, and Kemp 2006; Myhill and Jones 2006). It must be acknowledged here, though, that gender issues are either low on the agenda of teacher education programmes (Gray and Leith 2004), engender resistance (Poole and Isaacs 1993; Mills 2004), or require careful handling in order not to generate fear (Malmgren and Weiner 1999, 2001).

There has been a tendency among journalists, policy-makers and other social commentators, to connect the issue of boys’ performance in schools with the feminisation of teaching (Miller 1996). In some cases female teachers have been used as a scapegoat for boys’ perceived under-achievement. While, without doubt, data on gender differences in performance in public examinations in many countries indicate that girls’ performance is better overall (Drudy and Lynch 1993; OECD 2007; OFSTED 2003), there is no evidence that this is necessarily correlated with the feminisation of teaching (Drudy et al. 2005). Indeed such evidence as there is indicates the contrary – for example, a study of primary children in the UK points out that the gender of teachers had little apparent effect on the academic motivation and engagement of either boys or girls (Carrington et al. 2007). A recent international review of research on gender and education points out that with few exceptions, most empirical studies and reviews indicate that the sex of teachers has little, if any, effect on the achievement of pupils (Sabbe and Aelterman 2007).

Do boys need male teachers as role models?

A second strand of commentary on the feminisation of teaching (much aired in the media) addresses the lack of ‘male role models’ in teaching, especially in the primary sector. Concern about the growing feminisation of teaching relates to the perceived benefits for students and teachers of having more males working in schools, especially in terms of providing positive male role models for disengaged boys (OECD 2005). While there is widespread commentary and opinion on the assumed need for male role models, there has been until recently relatively little systematic research on th...