- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First published in 1987. This book began in Bali during 1970–72, during the author's Ph.D. research on the shadow theatre for the School of Oriental and African Studies in London. However, two subsequent trips to Bali in 1980 and 1984, when I studied other forms of dance-drama and ritual, greatly contributed to the work. The shadow theatre in Bali is described and its place in the society and culture explored. It is so called, as during the night performance puppets cast vibrant shadows against a white cotton screen which is illuminated by a flickering coconut-oil lamp.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dancing Shadows Of Bali by Angela Hobart,Hobart in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction and setting

In this book the shadow theatre in Bali is described and its place in the society and culture explored. It is so called, as during the night performance puppets cast vibrant shadows against a white cotton screen which is illuminated by a flickering coconut-oil lamp. The lamp hangs over a cross-legged puppeteer, or dalang, who is sitting in an enclosed, raised booth, facing the screen and at arm's length from it (see p. 129). The dalang is also one of the consecrated priests in the community. He manipulates the puppets while narrating a story from the sacred classical literature, so bringing to life mythic beings of both the natural and supernatural worlds. Musicians, who sit behind him in the booth, accompany the story with the clear, sweet tones of a small percussion orchestra. Through the rhythms of the shadows, the spectators on the other side of the screen from the puppeteer are drawn into other ways of seeing, or comprehending reality.

The shadow theatre exists, or has existed in the past, in a fairly defined strip of territory extending from China in the east, to Turkey and western Europe in the west. The island of Bali in Indonesia is unique in this context as it, more than any other area outside India, has retained strong ties with its Hindu heritage, yet extraneous influences – including ones from Chinese, Islamic and, more recently, European sources – have been subtly blended with an indigenous tradition to form a distinctive culture. The shadow theatre is deeply embedded in the social and religious life of the people and is among the most important and evocative vehicles of this culture which it reflects and helps create.

The study concentrates on four main aspects of the theatre: the mythology, the iconography, the performance and its social and cultural significance. Chapter 1 gives a background description of Balinese society and culture, which includes an introduction to the puppeteer, the dalang, then, in Chapter 2 the mythology which forms the basis of the plots is examined. Most of the characters are derived from the great Hindu epics, the Mahabharata and Ramayana. Mention is here also made to the servants who appear in the oral literature and are not found in the epics. While numerous individuals flit across the screen during a performance, the four main male servants are in some ways the most important actors on the stage.

Chapter 3 is an account of the puppets, their craftsmanship and symbolism. The puppets are flat cut-outs of hide, delicately chiselled and painted according to precise traditional regulations. While, in general, the puppets represent characters from the epics, they also form a self-contained symbolic system which sustains a select pattern of meanings relating to the villagers’ daily life.

The symbolic system, however, only gains efficacy in the performance for it is only here that the actors, the puppets, ‘wake up’ and ‘dance’ (Chapter 4). Each play takes place in a ritual setting and is a contrivance of great complexity combining varied dramatic stimuli of light, movement, voice, speech and music which are ingeniously woven together by the dalang to produce a rich and intricate theatrical fabric. At the same time, the screen acts like a threshold across which the gods are said to communicate to men.

There is, in fact, another type of performance, which has hardly been touched on by scholars. It is usually given during the day with the same flat puppets, but without a screen. Because it engenders little dramatic interest few spectators watch it. It takes place as one of a complex of rites in an area marked off spatially from everyday life in a household or temple. Chapter 4 also describes this type of performance.

Finally, in Chapter 5, the significance of both types of performance, the one dramatized at night and the other given during the day, is analysed. Both types of performance can be viewed as a unit which asserts a link, among other things, to the world as a cosmic unity and the sense of change and stillness in life. The religious nature of the theatre and its connection with morality emerge in this chapter. Here the relationship of the theatre to the other arts is also discussed as it has profoundly affected them. It is the most esteemed and conservative theatre form and hence its dramatic and aesthetic principles link it to the other dance-dramas, statues, reliefs and traditional painting. Of these the shadow play is regarded as the original form. Through these various manifestations the villager is able to probe and analyse his assumptions of self, in a world which is increasingly affected by modern trends, while retaining his human dignity.

Numerous works have appeared on myth, symbolism and ritual. Durkheim, who was one of the earliest scholars to study myth and ritual, which he saw as two sides of the same coin, wrote in 1915 on the traditional mythology of a society:

…. the mythology of a group is the system of beliefs common to this group. The traditions whose memory it perpetuates express the way in which society represents man and the world; it is a moral system and a cosmology as well as a history. (1976, p. 375)

For the scholar, both ritual and myth were part of the religious system and had the same function: to express and maintain social solidarity. Rarely, though, have the issues of myth and symbolism been discussed as linked components in theatre set within a ritual context where they acquire special force, giving meaning to experience, both collective and individual. While a number of detailed works specifically on the shadow theatre in South East Asia and India exist, these tend to concentrate on its literary, historical, philosophical or artistic aspects. The focus has also tended to be on Java where it is often associated with the court.

The shadow theatre in Bali, in contrast to its counterpart on Java, belongs predominantly to the folk tradition and expresses values which are essentially a product of the community as a whole. It is interesting that the people initially take an almost Durkheimian stance when describing the genre, drawing attention to the ethical values dramatized by the stories. In this role it is also seen as offering the spectators an integrated scheme for living and a design for selfhood and personal identity. However, the night performance is clearly more than just a didactic vehicle. Each show, if skilfully performed, is a work of art with aesthetic appeal which stimulates and entertains a crowd of villagers. At the same time, the shadow theatre possesses something of the sacred seriousness of classical Greek theatre. Like the performers of antiquity, the dalang is believed to be divinely inspired while on the stage, and so empowered to reveal a transcendental world or higher truth.

A number of scholars have influenced my approach in the book. Apart from Durkheim, Lévi-Strauss, Victor Turner, and Susanne Langer deserve singling out. However, above all I have been guided by the Balinese themselves. They are primarily interested in the individual performance as an event, brought to life by a particular dalang. This applies especially to the night performance; less so to the one given during the day as it does not set out to communicate to humans. The villagers, who watch the former type of performance, are highly critical of the dalang's technique in moving the puppets, his voice, his ability in creating and recreating the narrative, and his expertise in co-ordinating all the dramatic elements. In fact I witnessed one night performance where the villagers walked off in disgust after half an hour and the show petered to an unsuccessful end, the dalang returning home shamefaced. He had tried to mingle episodes from both the Mahabharata and Kamayana, but had failed to produce a coherent story which entertained. The villagers, moreover, pointed out that it was inappropriate to mix incidents derived from both epics in a single play. The audience also found fault with his voice which was harsh and rasping. That dalang has never again, to my knowledge, been asked to perform in that village.

An outsider's interpretation, taking in both the structuralist and semiotic perspectives, as well as the performance, is still necessary. I tend, however, to stress the latter aspect. Only by adopting such an approach can the wealth of data and indigenous information on the subject of dance-drama, and the shadow theatre in particular, be analysed. It then emerges that the shadow play is a unique vehicle for disseminating the Indian epics, although these are ingeniously modified and adapted to fit the Balinese context. Further the principles underlying the shadow theatre can then be explored and their similarities or differences to those of the other art forms investigated. Ultimately, it is essential to see the shadow theatre in the light of the whole society, as part of the fabric of the life of the villagers, rather than as a separate and isolated activity.

Balinese society and culture

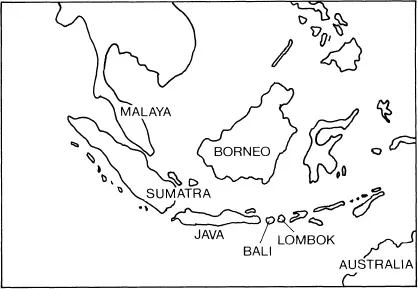

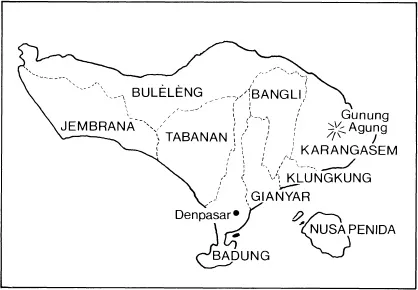

Bali is a small, fertile island, covering about 5,620 square kilometres. It lies just south of the Equator, to the east of Java and to the west of Lombok, but separated from them by dangerous waters (Map 1). As such it is one of the many islands comprising the Indonesian Archipelago. Because of its ecological affinities with Java, it is generally included within the tropical rain forest of central South East Asia. The backbone of the island consists of a chain of volcanoes, the highest of which is Gunung Agung to the east, rising over 3,000 metres. Set within the volcanoes are large crater lakes which are the main source of water for the island. Over two million people live in Bali, the bulk of whom are concentrated on the gently sloping plains of the southern part of the island. This region with its rich soils is intersected by numerous streams and rivers which flow down the mountains, cutting deep into the soft volcanic rock. The tightly clustered villages or hamlets (banjar) are often perched on top of ridges, surrounded by terraced rice-fields. They are linked to one another by paths or roads which more or less follow the courses of the streams from the interior to the coast, cross-cut by others from east to west, which are breached at regular intervals by gorges fanning out from the mountains.

Map 1.1 South East Asia

Map 1.2 Bali

Traditionally Bali contained some eight kingdoms. The most eastern of these, Karangasem, had strong links with Lombok, where Balinese immigrants colonized the indigenous Sasak people. The kingdoms were governed by aristocratic families under the titular overlordship of a king, raja. Regions within the kingdoms were ruled over by princes or aristocrats who often lived in elegant courts, puri, possessed extensive agricultural estates and kept many retainers. After the conquest of south Bali by the Dutch in 1908, the power of the indigenous rulers was gradually curtailed, first by the establishment of the colonial administration and then by the Indonesian Reform Laws in 1960. Since 1970, however, there have been further changes in the structure of the administration and the island now forms one province of the state of Indonesia government and the former kingdoms have become regencies or local administrative centres (kebupatèn) (Map 2). The capital of the island is Denpasar.

According to tradition the heartland of Balinese culture is in the south – in Gianyar, Bangli and Klungkung. This was the region most exposed to early Indo-Javanese influences, and it is here that the old court capitals flourished: first Pèjèng, then Gelgel and Klungkung. The ruler of Klungkung, the Déwa Agung (literally the Supreme King), was nominally the sovereign of the whole island until its colonization by the Dutch. Even today, the precedence of the regent of Klungkung over the other princes is reflected in his title.

Balinese social structure is complex. It is noted for its stratification into ranked descent groups, or wangsa (peoples): Brahmanas, Satriyas, Wèsyas and Sudras, according to an ideology similar to the Indian caste system, with spiritual and temporal power being distinguished between the Brahmanas and Satriyas respectively. While Wèsyas in India are often merchants, in Bali they are subsumed effectively under the Satriyas. Further, while the castes above and below them are relatively stable, the Wèsyas are involved in intense competition to achieve upward mobility. The three high castes are said to be descended from aristocrats who came over from the great Hindu Javanese kingdom of Majapahit when it fell at the end of the fifteenth century AD to the onslaught of Islamized coastal sultanates. The Sudras, or jaba, literally outsiders to the court, as they are common...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- 1: Introduction and Setting

- 2: The Literary Basis of the Shadow Theatre

- 3: The Puppets: Construction, form and Symbolism

- 4: The Audience and the Performance

- 5: The Place of the Shadow Theatre in Balinese Culture and Society

- Bibliography

- Index