- 332 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Swedish Signal Intelligence 1900-1945

About this book

A history of Swedish interception of radio and telegraph messages during World Wars I and II providing a valuable background to Swedish military operations at this time. This should prove a valuable work for anyone interested in the intelligence systems at work during wartime.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Swedish Signal Intelligence 1900-1945 by Bengt Beckman,C.G. McKay in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Wider Background

On 18 October 1939, as dusk fell on Stockholm, the Royal Palace, the Riksdag, the Palace of the Prince Royal, which housed the Ministry for Foreign Affairs, the Royal Opera House and the City Hall were all illuminated in a flood of light to celebrate the presence in the Swedish capital of three distinguished guests. The King of Denmark, the King of Norway and the President of Finland accompanied by their foreign ministers had come, at the invitation of Gustav V, King of Sweden, to take stock of certain ominous developments in the region and, perhaps still more, to give some lively manifestation of Nordic solidarity. In less than two months, great and decisive events had taken place: the Soviet Union had signed a pact with Nazi Germany; Hitler’s army and airforce had struck against Poland; Britain and France had declared war on Germany; and the Red Army had completed the liquidation of Poland, by occupying the Eastern part of the country, allegedly to ‘protect the White Russian and Ukrainian minorities’. Now some new scheme on the part of Stalin was in motion. After the successful intimidation of the three Baltic States — Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania — the pressure had switched to Finland.

Just before ten, a mighty procession with the flags of the four Northern countries borne proudly side by side and heading the convoy, converged to pay homage to the visitors. They duly appeared on the balcony of the Palace; massed choirs sang; and there were resounding ovations for the visiting Heads of State, in particular for President Kallio. It had been a moving occasion.

Next day, further discussions took place between the foreign ministers. Afterwards the three kings and the president spoke on radio. In his talk, Sweden’s monarch observed:

We consider it as one of our essential assets that each and every one of our countries can in complete independence implement the tested policy of impartial neutrality to which all the Nordic countries have subscribed.1

The actual fate of the four nations during the Second World War was to prove very different. Denmark and Norway were attacked, overcome and found themselves faced with long years of German occupation. Finland was to be embroiled in three separate conflicts: first in the Winter War, following the Russian attack on 30 November 1939; next in the Continuation War, then with the launching of Barbarossa, it reentered the struggle against Russia; and finally, in efforts to expel German units from Finnish soil after the FinnishSoviet Armistice of 1944. Sweden alone — albeit at some cost to the doC-T-Rine of impartial neutrality — managed to weather the storm without having its territory drawn into the conflict being waged all around it.

A small state’s room for manoeuvre in a war between great power blocs is circumscribed and the price of miscalculation may be high. Sweden’s wartime coalition government with the Social Democrat, Per Albin Hansson, as Prime Minister and Christian Giinther, a career diplomat, as Foreign Minister was faced with the unenviable situation of being responsible for a country which, after the events of April 1940, would be hemmed in on all sides by the powerful German war machine which had shown its paces in lightning attack. Furthermore, a short way across the waters of the Baltic and on past the rooftops of Helsinki, Tallinn and Riga lay that other dictatorship — Stalin’s Russia, the Russia of the Five Year Plan, the Soviet Secret Police and the Communist Revolution but also once upon a time the Russia of Peter the Great, in short a country with longestablished strategic ambitions in the Northern and Baltic region. Soon it would be embroiled in a life and death struggle with Nazi Germany, its onetime partner in peace. But what would be the outcome of that conflict? Obviously there was an urgent need to follow as far as possible changes in the general strategic situation, weighing up in particular their likely implications for the Northern and Baltic region and keeping track of possible threats to Swedish interests. Our task is to show how this need was met. In the process, we shall discuss the historical development of signal intelligence, both in general and in the particular case of Sweden. Let us begin with the general picture.

Like prudent motorists in the countryside at night, governments prefer to drive with the help of their lights. It is the task of intelligence services to throw light on dark places. For this they make use of a wide spectrum of sources. A government report on Swedish military intelligence lists no less than fourteen basic types.2 Satellite reconnaissance illustrates a more recent method of intelligence collection. The human agent or spy is an ancient (but still used) form of secret source. Another traditional source, more relevant to the present work, is the cabinet noir or Black Chamber, that is to say an organisation devoted to the interception and decryption of communications. Several works have been devoted to the history of this practice during the eighteenth century: Vaille has dealt with the French Post Office; Stix has tackled Austrian efforts; Brikner has given insights into Russian practice; and Ellis has dealt with the Secret Office in England.3 The use made of Black Chamber activity was at times rather sophisticated. Thus, in Russia, Catherine the Great in addition to making use of information received from her own interception service, also conspired to mislead other governments by including artfully planted disinformation in her own correspondence which she calculated would be intercepted by them.

More typical of standard practice was the following. In the 1770s, the British Minister in Stockholm was kept abreast of French secret intrigues in Sweden through a fairly continuous inflow of information from the Foreign Office in London. But what was the source of this valuable intelligence? One view held that it emanated from France where Lord Harcourt, the British Ambassador was reputed to have gained access to French diplomatic reporting through a wellplaced agent. It was an explanation which the very language of contemporary British despatches with their allusions to ‘my correspondent at Paris’, ‘our correspondent at Paris’ and ‘our old correspondent’ would seem to support. Yet a careful analysis of the documentary evidence suggests that the true explanation was quite different: the correspondence between the French Minister at Stockholm and Paris had been intercepted en route through Germany. The intercepts had then been passed to the Hanoverian chancellery, ‘the German Office’ in London and from there had been given to the British government. The expression ‘the correspondent in Paris’ was merely a cover designed to conceal the postal interception service in Hanover.4 It is amusing to note that the same device was used in the Second World War when Ultra material was initially distributed as emanating from a human source, Boniface.

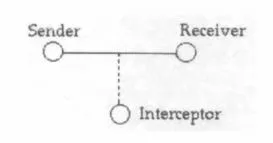

The above example shows that what the British Admiralty used to call ‘special intelligence’ — and what current terminology labels comint5 (communications intelligence) — is in no sense a completely new phenomenon. Although the means of communication may vary, its basic structure is strikingly simple:

But whereas the Black Chambers of the eighteenth century were relatively small and were largely concerned with diplomatic correspondence, the revolution in communications technology brought about successively by telegraph, telephone and radio, and the changing nature of warfare, transformed their modern successors. Above all, the quantity of information in transmission increased dramatically. In exploiting the new techniques for intelligence purposes, staffs had to be expanded; new skills were needed and these had to be incorporated within an efficient administrative framework which ensured the swift processing of incoming information and the circulation of relevant material to the various user departments and policymakers. By the end of the Second World War, what had started out in several countries as tiny secret offices of state had become significant bureaucratic organizations, run on quasi-industrial lines and employing a large staff of full-time technical experts. In speaking of the modern intelligence centre, three British experts summed up the position rather well:

it may be compared with the assembly department of a manufacturing firm for it receives bits of information from its various sources and assembles them into a finished article which it hands on to the user.6

The industrial metaphor was to be preserved in the language of sigint organisations after the Second World War with their Offices of Production and of R&D and their talk of the procurement and distribution of their product. Although some of the skills plied in the sprawling new complexes had a long history, the old cabinet noir, with its tiny corps of practitioners, seemed as dead as some exotic guild of the middle-ages.

The word ‘communications’ has traditionally been used to cover both transportation and the transmission of information. Common to both is the bridging of distance. In the case of the postal service, transportation and the transmission of information coincide in the conveyance of a concrete physical object, namely the letter. But it had been early appreciated that information could be sent more rapidly by dematerializing it and treating it more abstractly as auditory or optical signals. The tomtom provides an example of the former. The Greek dramatist Aeschylus provides an illustration of the latter. In Agamemnon, the first part of the Orestes trilogy, Clytemnestra announces that Troy has been taken:

Chorus: Who could have brought the message with such speed?

Clytemnestra: Hephaistos, God of Fire. He sent the flame from Mount Ida and from beacon to beacon, from top to top, it spread like wildfire.

Thereafter follow the details of the route taken by the signal: from Ida to Hermes’ crag on Lemnos and thence to Athos etc.

Yet the practical development of the optical telegraph had to await a further extension of man’s senses in the shape of the achromatic telescope invented by Dollond in 1757.7 This allowed the signal stations in the chain to be spaced more widely apart. This clearly saved in installations and manpower but it also had the effect of increasing the transmission rate, since the fewer the intermediate stations, the fewer the delays in receiving and forwarding the signal.

The best known system of optical telegraph was that demonstrated by Claude Chappe in France in 1791 where the basic signal was defined by a set of movable arms which could occupy one of 196 different positions.8 The system was designed to be used in accordance with a codebook consisting of 92 pages, each page consisting of 92 numbered words. Contemporary accounts speak of an average transmission rate of 3 signals per minute in favourable weather conditions, although on longer lines e.g. Paris-Toulon, which had 120 stations, a more realistic estimate seems to have been one signal per minute.9

Other systems of optical telegraph were developed elsewhere.10 In the autumn of 1794, an optical telegraph traversing the 10 kilometres between the Royal Palaces of Stockholm and Drottningholm, was tried out. The experiment proved a success and the system was significantly extended. In the Finnish war of 1808–1809, it proved its military worth. In 1834, it was reorganized as a military telegraph corps with C. F. Akrell of the Topographical Corps in charge. It was still being used during the heightened state of alert brought about by the Crimean War, with the network in action on both the East and West coasts of Sweden.

The Swedish optical telegraph had been devised by A. N. Edelcrantz, an ingenious and versatile savant.11 Instead of the movable arms of the Chappe system, the constituent units consisted of 10 shutters, one at the top with three rows of three beneath, each of which could be set to ON (vertical) or OFF (horizontal). In the latter case, the shutter in its horizontal position was invisible from the next station in the chain. Clearly this binary shutter arrangement allowed 210 i.e. 1024 different configurations. A displayed configuration of shutters was discernible by means of a telescope from distances of up to 10 kilometres. Each configuration was assigned a unique expression according to the following system: the topmost shutter was assigned the letter A; the 3 shutters directly beneath were assi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Also in the Intelligence Series

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1. The Wider Background

- 2. Swedish Developments 1900-1918

- 3. The Interwar Years

- 4. The Winter War and the Chattering Bear

- 5. Tales of a Secret Writer

- 6. A New Authority

- 7. Security Matters

- Summary

- Documentary Appendix

- Glossary of Technical Terms

- Sources and Bibliography

- Name Index

- Subject Index