![]()

PART I

INTRODUCTORY SURVEY

![]()

1

THE ANCIENT TRADITION

In order to survey the development of ideal planning in Western Europe it is necessary to consider briefly the ancient traditions upon which this evolution is based. As the late Professor Frankfort cogently pointed out in his book on The Art and Architecture of the Ancient Orient, in Ur ‘the temples and palaces were the only buildings with aesthetic pretensions’.1 It is furthermore true to say that it is on such buildings that the planners concentrated in the Orient whilst the dwellings of the less fortunate members of the community were treated with scant attention. The Assyrian proverb,

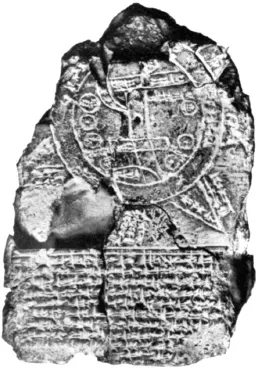

Figure 1 Clay tablet, c. 600 BC, depicting the regions of the world

The man is the shadow of the god

The slave is the shadow of the man

But the king is god.

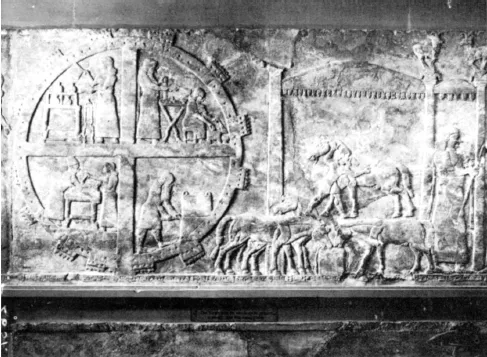

epitomises a static view of civilization,2 in which palaces and ziggurats with their precincts were regarded as representations of and substitutes for cosmic relationships, the underlying basic pattern of planning being the square. It occurs in a small Babylonian clay tablet, depicting the regions of the world, and also in a relief from Nimrud, showing four domestic occupations in the subdivisions of a fortified encampment (both of which are in the British Museum). The latter seems reminiscent of the Biblical story (Genesis 40) about the functions and dignity of Pharoah's butler and baker. (Figs 1 and 2.) It is against this background that the novel developments of the Greek, Roman and Jewish concepts of the ideal city have to be set.

Figure 2 Relief from Nimrud showing four domestic occupations in a fortified encampment

THE GREEK TRADITION

It is in classical Greece with its City States, and in the Hellenistic and Roman Empires, that a significant and gradual change with regard to overall planning took place, although the early stages of these developments are still largely unknown, pending unforeseeable results of future excavations. The admirers of the suggestive and unplanned effect of the Acropolis in Athens may well differ in their taste from the contemporaries of Plato, who in the Fifth Book of his treatise on Laws demanded a city as near as possible to the centre of the country, an acropolis circled by a ring wall, and divided his ideal town into twelve parts, planned for five thousand and forty plots, each of which was to be subdivided, in order to allow for the equalization of the quality of land, the same citizen receiving a superior central portion and an inferior one at the periphery.

In the Timaeus and Critias the ancient city of Athens is characterized by various classes of inhabitants: the priests, the artisans, the husband-men and warriors. The separation of these classes is mentioned in the former and presupposed in the descriptions of the latter. It is likely that in these statements Plato reflected and modernized ancient conceptions of static and harmonious communities which were associated with the abodes of the gods and the palaces of the kings.3

In the same works Plato also described the legendary island of ‘Atlantis’, which contained a mount, encircled by five zones of land and water, and a palace enclosed by round walls, on the ‘secret island’, presumably an artificial subdivision of the larger isle. There was a rectangular plain, divided into sixty thousand plots, each of which was a square.

In this manner the two basic mathematical forms, the square and the circle are found in juxtaposition. These elements, universally seen in all civilizations, remained the ‘tracé régulateur’, in the sense in which Le Corbusier uses the term, right up to the contemporary period. The fact that Plato mentions the plain is significant, not only because of its regular form, but also because a planned environment is more easily realized in a flat region, whereas mountainous sites largely super-impose their own shape on the human matrix. On the other hand hills and mountains and their protecting walls achieve the simplest type of strategic protection. For this reason a rudimentary form of circle appears in primitive civilizations, as also does a vaguely round or elliptic hut, in which the angles are anxiously avoided. Such shapes only partially reflect the character and regularity of the true circle.

Plato's prototypes for the layour of Atlantis may be connected with pre-Hellenic fortifications in Greece or the ring of walls encircling Mantineia about 460 B.C.4 Isolated central buildings, such as the Tholos of Epidaurus, reveal the circle as an aesthetic factor, but the same principle according to the evidence available, seems not to have been applied consciously to town-planning. Hellenistic cities, when planned, belonged to the chequer-board type, as seen in Miletus, Priene, and also originally in the Piraeus, as built by Hippodamus of Miletus. From these facts it appears that Plato's sources are not found in observations regarding his environment, but spring from traditions of a magical or cosmological nature; they are used in a formalized manner, expressing primarily aesthetic concepts of regularity and order, which in turn may well be indebted to the Pythagorean tradition.

The division regarding social stratification in the second book of Aristotle's Politics appears similar to that found in the Timaeus and Ciitias, and is attributed to the theories of the same Hippodamus of Miletus, who thus appears as a thinker as well as an architect.5 Three classes – artisans, farmers and warriors – are described, a fourth class of priests is presupposed, since the land is divided into three parts, sacred, public and private. In his turn Aristophanes in the Birds was aware of the concept of circular geometric cities, when he poked fun at Plato, his disciples and the rigid planners. The combination – architect and planner – found in the person of Hippodamus was to become a characteristic feature in European evolution.

In an interesting article Ivanka attributed to Aristotle himself the views attributed to Hippodamus in the Politics, since they form a separate part of the treatise, and may originally have belonged to a different work. Ivanka suggests that the recommendations here given were to guide Alexander the Great in his plans for Alexandria, in order to establish a city in the Greek democratic tradition as opposed to the autocratic Eastern pattern.6 Greeks and non-Greeks were to live separate lives in different quarters and their occupations, farming for the natives, trade largely for the Greeks, were to emphasize the separation.

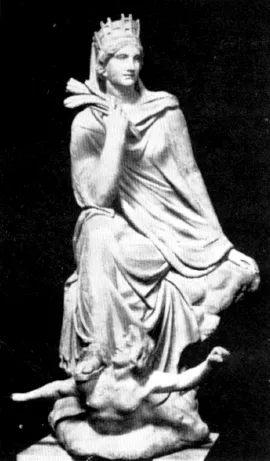

If this theory is accepted, then it has to be assumed that Aristotle used an ancient pattern of society, as preserved in the Critias, and transformed it to serve his political purpose. He failed, however, in exerting his influence, since Alexander attempted to unify the various populations under his autocratic rule, thus becoming the creator of the vast Hellenistic cities. However, when the Grecian symbol of the polis, the goddess of Fortune, Tyche, crowned by a circlet of walls and peacefully seated, was associated with the newly created towns, such as Alexandria and Antioch, she still personified the tradition of the enclosed and protective aspect of the city state.7 The statue in the Vatican Museum, representing the Tyche of Antioch by Eutychides of Sycion, is a marble copy of the bronze original, and shows the goddess, following the usual iconography, holding a sheaf of corn. The river god Orontes is seen at her feet. The work is a telling symbol of womanhood regarded as a protective and bountiful force, allied to good fortune and the prosperity of the city. (Fig. 3.)

Figure 3 The Tyche of Antioch

Figure 4 Tabula Peutingeriana, detail

The type was frequently found in monumental statues as well as on numerous coins and its popularity persisted in the Roman period. It is reflected in a medieval copy of the ‘Tabula Peutingeriana’, an earlier Christian adaptation of a road map of the Roman world, now in the Vienna National Library. Here the cities are shown in perspective, enclosed by their walls, and smaller centres by groups or individual buildings in foreshortening. Antioch is represented by Tyche, seated, a halo round her head, Orontes at her feet, whilst Roma, within her circular walls, is enthroned holding up the orb, and Constantinople is presumably characterized by the column of Constantine, erected in A.D. 331. The feminine figures, which were originally based on the prototype of the protecting city-goddess of Hellenism, were altered into masculine ones during the medieval period, showing how much their underlying meaning had been misunderstood and forgotten.8 (Fig. 4.)

THE ROMAN TRADITION

The only extant treatise by a practising architect of the Roman period is the work by Vitruvius, De Architectura Libri Decern, presumably belonging to the Augustan Age. Owing to the author's lack of originality, for which posterity has cause to be thankful, this remarkable document reflects the dominant trends of its period faithfully. The emphasis is on architecture for the rich and powerful, whilst the social question looms, hardly recognized as yet, in the background....