![]()

‘Our Wicked Foreign Game’: Why has Association Football (Soccer) not become the Main Code of Football in Australia?

Roy Hay

Introduction

Soccer, ‘our wicked foreign game’, is not the main code of football in any state in Australia, but is probably the second in most states if measured by spectator attendance or participation.[1] In Victoria, Australian rules is number one, while in New South Wales, rugby league is the dominant code. The phenomenon is not unique to Australia. None of the white dominions of the old British Empire or the former British colony, the United States, has soccer as its main code, with the exception of South Africa where the non-white population has taken up Association Football.[2] In most of these countries soccer is characterized as a migrants’ game, even though many of the migrants playing or watching the game are of second or later generations. Explanations for the secondary position of soccer in Australia ought therefore to be compared with those for these other countries, and if we seek a comprehensive explanation of this phenomenon then the Australian story ought not to vary too much from those applied to the others, unless it can be clearly shown that Australian experience and conditions were indeed different.[3] This essay concentrates on the domestic experience in Australia, with a view to introducing and outlining some of the issues which might be drawn into an effective international comparison.

Before doing that, though, it is worthwhile to look more closely at the true position of soccer in Australia today. If the men’s code is secondary, that is not necessarily true of the women’s game in Australia. Women’s soccer is also the top code in the United States where the team is the current Olympic champion and runner-up to Germany in the FIFA Women’s World Cup. In Australia, the women’s game is at least as popular as any of the other codes of football. The national team has qualified for the Women’s World Cup and the Olympic Games. Women’s soccer is claimed to be the fastest growing sport in the country. Separate organizations for women’s soccer (and indoor soccer, futsal) have now been brought together under the Football Federation of Australia. Women’s matches were played alongside men’s games at the Olympic Games in Australia in 2000 and when the men took part in a friendly international against Iraq in 2005. It is arguable that an opportunity exists to turn soccer into a more appealing game to families by involving women as players, administrators and spectators, as well as mothers of the next generation.

It is also easy to underestimate the significance of soccer in Australia by simply relying on the mainstream media. Even though they are very rubbery, participation rates in the football codes, particularly among boys and girls up to the age of 15, show soccer leaving the other football codes in its wake. ‘The sports that attracted most boys were outdoor soccer (with a participation rate for boys of 20 per cent), swimming (13 per cent), Australian rules (13 per cent) and outdoor cricket (10 per cent). For girls, the most popular sports were netball (18 per cent), swimming (16 per cent), tennis (8 per cent) and basketball (6 per cent).’[4] Female registrations in soccer in New South Wales rose by 28.5 per cent between 2002 and 2003, reaching 23,305 in the latter year. Junior female registrations (6–17 years) were up by over 30 per cent.[5] In 2005 an 18 per cent increase in total registrations to 14,000 in Sydney’s north shore district of Ku-ring-gai put extreme pressure on facilities for soccer in the area.[6]

Crowds for competitive international soccer matches in Australia, especially World Cup qualifiers, have been excellent. Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) World Cup qualifiers against Iran in 1997 and Uruguay in 2001 drew capacity attendances to the Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG) and over 100,000 saw the Olympic Games final in Melbourne in 1956. An average of 47,000 spectators attended double headers at the MCG during preliminary rounds of the Sydney Olympics of 2000, even though this tournament was limited to male players under the age of 23 and the programme each night had one male and one female game. When Australia played 93,000 were present.[7] National Soccer League (NSL) crowds between 1977 and 2003 were often regarded as woeful by comparison with those of the Australian Football League (AFL), but, particularly in Perth and Adelaide, they were not wildly out of line with rugby union or rugby league crowds. Also, Australian attendances are comparable to those in the top leagues in many countries around the world, for example Scotland with the major exception of Celtic and Rangers, the Old Firm.[9] Nevertheless, despite its occasional triumphs on the field and its precocious establishment of the first national league of any of the football codes, soccer in Australia has never come close to establishing itself as the primary form of football in a country which is often said to be obsessed by sport.[10] Why is this?

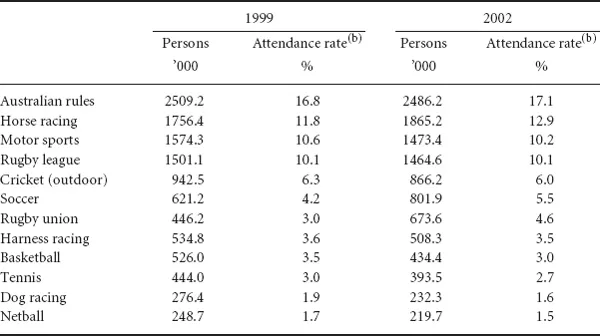

Table 1 Attendance(a) at selected sporting events – 1999 and 2002[8]

(a) Attendance at a sporting event, match or competition as a spectator by persons aged 15 years and over in the 12 months prior to interview in April 1999. The 2002 survey referred to people aged 18 years and over.

(b) The number of people who attended, expressed as a percentage of the civilian population aged 18 years and over.

There were changes in the survey methodology between these two surveys, so the figures should not be used for comparison without reference to the Explanatory Notes in the 2002 document. The 2002 document records different figures for 1999.

There is no single reason. Some explanations lie outside the code, others inside. Many reach back into the history of the game since its inception in the nineteenth century. They set a pattern which became established very early and influenced perceptions of the game thereafter, being reinforced again and again by developments within the code and in the wider society.[11]

Formative Stages

In the early part of the nineteenth century games of football were not as rigidly defined and codified as they later became. Bill Murray argues that timing is critical and that once a sport becomes established in a society it is difficult to dislodge. He also attributes the lack of impression made by soccer in the United States and the white dominions in part to social snobbery. As a predominantly working-class game, soccer did not receive support from British elites seeking to influence their colonial brethren. Nor did it appeal to colonial elites. He also suggests that the greater availability of open space and grass militated against the development of soccer compared with cricket and Australian rules, which were more suitable to societies with more land, though football and soccer both developed in the inner cities and the near suburbs where land was at a premium.[12]

There is obviously a class dimension to the status of football in Australia. Football has been a working-class, professional game, while cricket and rugby union, though often transcending classes in certain localities, have tended to be associated with middle-class and upper-class groups whose social leadership resisted challenge effectively until at least the turn of the twentieth century.[13] As a general rule British officials and teachers did not promote soccer and the process was left to seamen, engineers, artisans and the like.[14] As Richard Holt puts it, ‘Football also failed to become officially established as an institution of Empire’.[15] Australia’s elites, with certain exceptions which will be addressed later, have not warmed to soccer and indeed have kept clear of all the football codes until relatively recently. Lower-class migrants, on the other hand, have taken to the game. This invites comparison with the United States where, according to Foer, the two social groups which have supported the game are elites and Latin-American immigrants.[16]

The sources of early British migrants to Australia may have been significant. If they were predominantly drawn from the lower orders of urban London, rural Southern England, Ireland and Highland Scotland, they would have been less likely to have brought a species of soccer with them than if they had come from the North of England or the central belt of Scotland, where the game had a much greater hold by the 1880s. This hypothesis is put forward as speculation rather than established fact at this stage, but it is worth exploring.[17] According to James Jupp, ‘Despite a widespread belief in Australia that a high proportion of English free settlers came from the industrial North, there is little evidence from available figures that this was true until the 1880s’.[18] The North was also under-represented in assisted migration figures between the 1860s and the 1880s.[19] J.C. Docherty mentions the political and social concerns of immigrants to Newcastle in New South Wales and their strong collectivist approach, but does not explain how this became a pioneering area in the development of soccer in Australia, just as it was in Newcastle-upon-Tyne in England. Scottish migrants were also over-represented in the Newcastle area.[20] Jupp, on the other hand, asserts that ‘Soccer established a mass following in the Hunter Valley region, where there was a concentration of immigrants from Scottish and North East mining areas, but otherwise was unable to displace rugby and Australian rules’.[21] If the migration boom of the 1880s had a higher proportion of northern English and Scottish migrants then it is probably significant that this was the decade in which soccer became prominent for the first time as a separate code in Australia, with the foundation of a number of clubs in the major eastern cities and industrial centres and the first interstate matches taking place.[22]

The English-speaking migrants to these new colonial societies did not absolutely need their sports to assist them to come to terms with the places in which they found themselves. Some subsequent generations of migrants did. We will be returning to this point later. Nevertheless, the Scottish and English migrants who set up clubs in Australia began a tradition of naming them after their homelands or geographic areas, or used terms which were current in the names of existing clubs overseas, so we have Caledonians, Northumberland and Durhams, Rangers, Celtics, Fifers and others to mark the newcomers.[23] These clubs became enclaves where new migrants could find like-minded people at a time when there were few domestic organizations in Australia catering for them.[24] Some British migrants were brought to Australia by soccer clubs, or joined them within days of arrival, including the father of the former Australian cricket captain, Bobby Simpson, who was offered £50 a season to play for Granville in Sydney around 1926. Jock Simpson was probably a rarity, since semi-professional soccer was uncommon in Australia in the 1920s.[25] More typical would be the experience of William MacGowan, who was signed up to play with Ford’s soccer club in Geelong as soon as his feet touched Australian soil in Melbourne in 1926.[26] Ford had set up its assembly plant in Victoria in that year, and its workers very quickly entered a team in the local league. By the 1950s semi-professionalism was more common and overseas players were actively sought out by Australian clubs.[27]

Andrew Dettre has attempted to trace the colonial pattern to the very origins of European Australia. He argues that the early involuntary migrants left their stamp on the culture and the sports in Australia and elsewhere: ‘Those people [early British settlers in Australia, America, Canada and South Africa] included convicts and others similarly disillusioned and determined to forget what they had left behind. Theirs was a rough, tough life-style and when it came to diversion they preferred a form of blood sport. Hence we saw the development of rugby, Australian football, gridiron and ice hockey.’[28] It is an interesting thesis, but it is hard to accommodate the attraction of cricket in this interpretation. It was cricket which became Australia’s national sport in the nineteenth century, precisely because it was a sport in which Australia could compete with the colonial metropolis.[29]

Australians proved they could organize themselves on a private enterprise basis to compete effectively against the Eng...