![]()

Leadership and Service Improvement: Dual Elites or Dynamic Dependency?

TOM ENTWISTLE, STEVE MARTIN & GARETH ENTICOTT

Introduction

According to central government, effective local leadership is at the heart of the modernisation agenda. Vibrant Local Leadership – a government strategy document published in 2005 – explains that the ‘elected councillors and council officers’ charged with providing leadership are ‘absolutely vital to the quality of life enjoyed by our citizens’ (ODPM, 2005a: 7).

For members, changes prompted by the Local Government Act 2000 have, in the vast majority of councils, focused political leadership in a small executive. The intention is that this will promote ‘a strong, visible and more individualised form of leadership with an associated heightening of accountability’ (Lowndes & Leach, 2004: 557). Meanwhile, since 2002, officers have come under increasing pressure from comprehensive performance assessments (CPAs) to provide effective leadership of their authorities by offering, amongst other things, ambition and focus, an ability to set clear priorities and to make good use of available resources.

It is not clear though how these two strands of officer and member leadership work together. While the Government has argued that the leadership roles of councillors and officers can, to some extent, be differentiated into community and corporate leadership, key elements of the current ‘modernising agenda’ are encouraging councillors to become increasingly involved in the kinds of managerial issues that have traditionally been seen as the primary responsibility of paid officials. As officers and members have been increasingly attempting to exercise leadership in the same areas and the same ways, the extent to which they agree or disagree about the key issues facing their councils has become more and more important. Do leading members and managers operate as a ‘dual elite’ with a shared agenda for the corporate management of their authorities or do differences of perspective between the two groups which mean that their relationship is best characterised as one of ‘dynamic dependency’, resolved through negotiation and exchange on a case by case basis.

On the basis of extensive surveys of member and officer views conducted in 2001, 2002 and 2003, this paper considers the differences between members’ and officers’ views of service improvement and corporate leadership. We analyse recent changes in the leadership roles of members and officers and conclude that recent developments have increased the risk of overlap and conflict in the area of corporate leadership. We test this hypothesis by comparing members’ and officers’ responses to questions about current performance, approaches to management and the main drivers of improvement in their councils. We conclude with an assessment of the significance of the differences between members and officers and some consideration of possible explanations for those differences.

Who’s Leading Whom?

While acknowledging that a ‘subtle and dynamic partnership’ between leading members and managers is ‘not easily captured by a straight forward list of respective responsibilities’, the Government’s recently published Vibrant Local Leadership suggests a differentiated model of leadership (ODPM, 2005a: 27). Councillors, it suggests, should focus on community and neighbourhood leadership while ‘leading and enthusing an organisation to deliver the vision that political leaders have primarily shaped, is a critical challenge for the most senior managerial leaders’ (ODPM, 2005a: 27). Both the character of the new institutional arrangements put in place by the 2000 Local Government Act, and the rhetoric of the Government’s policy statements, imply that elected members should take a predominant role in community leadership, while senior managers should focus their efforts on corporate leadership.

Community leadership is a slippery concept (Martin, 1997; Sullivan & Sweeting, 2005), but current government policy clearly draws upon the notions of ‘community governance’ outlined by Clarke and Stewart (1994) and of networked community governance (Stoker, 1999; 2004). The 1998 White Paper explained that community leadership is ‘at the heart of the role of modern local government. Councils are the organisations best placed to take a comprehensive overview of the needs and priorities of their local areas and communities, and lead the work to meet those needs and priorities in the round’ (DETR, 1998: 62). The 2005 paper Vibrant Local Leadership makes the same point, explaining that councils ‘have a key role in leading their communities, focused on networking, influencing and working through partnerships, building on the governance arrangements for LSPs and approaches for Local Area Agreements’ (ODPM, 2005a: 31). While these high level leadership roles are core business for executive members, nonexecutive councillors are encouraged to look downwards to wards and neighbourhoods. ‘Neighbourhood leadership must’, the Government argues, ‘be a central element of every ward councillor’s role’. Non-executive members should play the leading role in ‘stimulating the local voice, listening to it, and representing it at council level’ (ODPM, 2005b: 16).

Whereas community and neighbourhood leadership is outward focused, corporate leadership is inward looking, concerned with the internal operations and organisational performance of an authority. Corporate leadership is, the Government says, vital to the effectiveness of a ‘modern’ local authority. Byatt and Lyons (2001: 11), for example, emphasise that ‘an important factor in performance in particular service areas is the quality of leadership and corporate governance of the authority as a whole’. The Cabinet Office Performance and Innovation Unit explains that leadership is ‘a key determinant of the success of organisations’ (Performance & Innovation Unit, 2001: 9). The Audit Commission (2002: 19) reports that ‘a serious and sustained service failure is also a failure of corporate leadership’. ‘Top performing councils have’, it argues, ‘sound corporate performance management, commitment to improvement, sustained focus on top local priorities, the ability to shift resources and make difficult choices’ (ibid.: 30).

The differentiation of leadership roles is not however as neat as the Government has suggested. With executive portfolios and scrutiny panels often mirroring departmental boundaries, the new political arrangements introduced in the wake of the 2000 Local Government Act, combined with the increasing emphasis on service improvement, have encouraged elected members to take a much greater interest in corporate and operational leadership. While the Government says that it wishes to see delegation of decision making to officers, new council constitutions, which have done away with the need to steer decisions through allegedly cumbersome committee proceedings, have made it much easier for portfolio holders to take executive decisions and adopt a far more ‘hands on’ approach (Leach & Wilson, 2002: 684). The intermingling of officers’ and councillors’ leadership roles is reinforced by the logic of democratic politics. Leach and Wilson (2000: 110–111) explain that: ‘Politicians know they will be judged not by what appears in a statement of strategy or policy, but by what happens on the ground’. Operational matters, or ‘task accomplishment’ as Leach and Wilson describe it, is therefore an entirely legitimate concern of elected leaders. Moreover, the professionalisation of political leadership, afforded by improved remuneration associated with modernisation, has allowed executive members to devote more time to these concerns (IDeA, 2004).

Where members and managers find themselves leading in the same sphere – as seems increasingly inevitable in the matter of corporate leadership – the nature and quality of member-officer relations assumes critical importance. The literature suggests four different models of that relationship. The first, or conventional, view has it that power rests solely with elected members who decide while ‘officers implement’ (Gains, 2004: 93). The second model suggests that, in reality, officers often dominate by virtue of their professional training, full-time, salaried and permanent positions (Alexander, 1982). The third model recognises that where members and officers are ‘all going in the same direction’ (Saunders, 1979: 224), a ‘dual elite’ of members and officers may allow for harmonious co-leadership (Gains, 2004: 93–94). But, as Gains explains in an elaboration of a fourth model, the relative power of elected representatives and officers varies according to the particular issues being considered, the individuals who are involved and the culture of their authorities. In practice, members and officers may therefore be in a state of ‘dynamic dependency’. With different perspectives, legitimacy and areas of expertise, members and officers need to exchange resources, negotiate and compromise to achieve their desired outcomes (Gains, 2004).

This thesis suggests that much depends on the extent to which members and managers share the same views on the performance and management of their authorities and the steps that need to be taken to secure improvement. Where there is ‘a shared agenda between the local bureaucratic and political elites’ (Gains, 2004: 93) this may result in the harmonious co-leadership of the dual elite model. If, however, members and managers hold very different views on these key issues, the result is likely to be disharmony or even outright conflict associated with dynamic dependency. There is some evidence of the latter. Fox (2004: 391), for example, cites an interviewee as complaining that: ‘Modernisation is producing a more interventionist culture which is causing chaos because most members have little idea of operational issues’.

In order to assess the scope for harmony or conflict in the exercise of corporate leadership, the remainder of this paper compares the views of executive members and senior officers of their council’s performance, approaches to management and the drivers of improvement. We analyse the extent to which members’ and officers’ views changed between 2001 and 2003, whether there is any evidence of convergence in their views over time, and discuss the possible implications for policy and research.

Research Methods

Most research on performance improvement in local government and public services has focused almost exclusively on the views of senior management, typically the chief executive. This paper, by contrast, draws upon longitudinal data from three in-depth surveys of a large sample of elected members, corporate officers and service managers undertaken in 2001, 2002 and 2003. The multi-respondent and longitudinal character of our surveys allow us to analyse whether councillors’ views of their authorities have been changing and how their perceptions compare with those of different groups of officers.

The structured surveys were completed by more than 1,300 respondents each year drawn from a sample of just over 100 authorities which was representative of all English councils in terms of current performance, levels of deprivation, region and authority type. The survey was completed by four different sets of respondents: executive elected members (the council leader and other portfolio holders); corporate officers (the chief executive, the director of corporate policy and the corporate Best Value officer); chief officers overseeing seven service areas; and service managers (assistant directors and service heads) of the same service areas. The seven service areas that we focused on (revenues and benefits, leisure and culture, education, housing management, planning, social services and waste management) were selected because they include a range of ‘back office’ and ‘frontline’ functions, and include both ‘white’ and ‘blue collar’ activities.

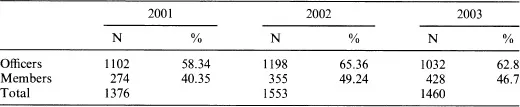

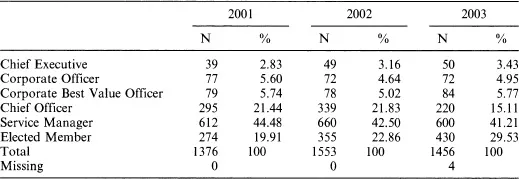

Response rates over the three years ranged from 58 per cent to 65 per cent for officers and from 40 per cent to 49 per cent for elected members (Table 1). On average 42 per cent of respondents were service managers, 24 per cent were elected members, 20 per cent were chief officers, and 14 per cent were corporate officers (Table 2).

Respondents were asked about three sets of issues: the performance of their authority; approaches to the management of services; and the factors that they believed were driving service improvement in the council. Chief officers and service managers were asked to report on their services, whereas members and corporate officers were asked to report on the authority as a whole. All respondents rated performance on four-point Likert scales, management approaches and drivers of improvement were rated on seven-point Likert scales.

Table 1. Response rates

Table 2. Respondents by role

All responses were analysed by year and by respondent group using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). This enabled us to identify differences between the groups in each year and changes in the views of each group over the three-year period. In order to test for significant differences between groups over time, the average response for each group of respondents was calculated for every authority in each year. Only authorities from which we received a response for each question for each of the four groups of respondents in every year were analysed. This meant that 66 authorities featured in this particular element of the analysis (see Table 4).

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and two tailed T-tests were used to test whether differences between respondents are statistically significant. Our analysis records three levels of statistical significance: the weakest (p < 0.1) suggests that there is a 10 per cent pro...