![]()

Chapter 1

Models of understanding

How family members continue to be pathologised and misunderstood

How professionals and academics have described and conceptualised the experiences of the wives, mothers, fathers, husbands, sisters, brothers and other family members who experience at first hand a relative’s excessive drinking or drug use is the subject of this chapter. In many respects it is a sorry tale, but one that helps us understand one of the reasons why family members might have been marginalised in the past. It helps us understand why the research to be reported in later chapters was necessary and provides a vital part of the context for the interpretation of its results.

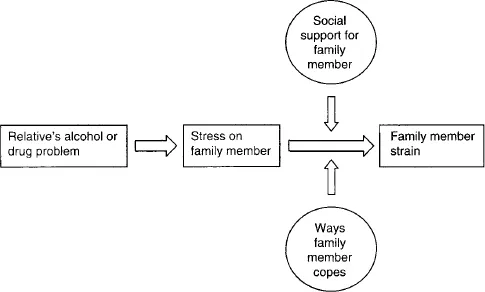

A number of different models or perspectives on the subject are presented in the chapter, starting with the form of stress-coping model which informed the present work. That model is therefore the one which the authors of this book support and the one that we recommend as a basis for improving professional responses to family members. It is the way of seeing the subject with which the research to be reported later began, and in modified form the way of seeing the subject with which the book concludes. The present chapter then proceeds by presenting a number of rival perspectives, namely, the pathology, codependency and systems models. Lacking from all preexisting perspectives, including the stress-coping model with which we started, is due attention to social and cultural context, and the present chapter concludes with a consideration of some possible elements of a social contextual perspective.

The stress-strain-coping-support model

The stress-coping model, or to give it its full name, the stress-strain-coping-support model (Orford, 1994, 1998), owes its origins and much of its terminology to a line of research in health psychology and related disciplines that expanded greatly in the later decades of the twentieth century. Early seminal writings included those by Lazarus and Folkman (1984) and Holmes and Rahe (1967). It conceived of certain sets of circumstances that people face in their everyday lives as constituting long-standing, stressful circumstances or conditions of chronic adversity. Such conditions embraced war or chronic unemployment, but they also included chronic personal illness or living with a close relative with such illness. Different people might respond to stressful conditions in different ways, and some of those ways might be better for their health than others. The mechanical analogy of stress and strain was thought to be useful: if stress was not satisfactorily coped with, strain would be evident in the form of some departure from a state of health and well-being. The idea that people differ in the amount or adequacy of social support that they receive from other people (Cobb, 1976; Tolsdorf, 1976) and that social support might for some people be effective in buffering the effects of stress on strain (Cohen and Wills, 1985) was an important addition to the basic model. But the central idea is that people facing such conditions have the capacity to ‘cope’ with them much as one would attempt to cope with any difficult and complex ‘task’ in life. It incorporates the idea of being active in the face of adversity, of effective problem solving, of being an agent in one’s own destiny, of not being powerless. In one form or another, the stress-coping model has been applied to a very wide range of conditions and circumstances (Orford, 1987; Zeidner and Endler, 1996) including coping with cancer and caring for a close relative with dementia (Gallagher et al., 1994).

The main components of the stress-coping model, when applied to families where a member of the family has a drinking or drug problem, are shown in Figure 1.1. Like all perspectives or models of human experience, the coping perspective makes certain assumptions and draws certain analogies. Like all assumptions and analogies, those made from the coping viewpoint are simplifications. They are not total truths, but rather working tools. The first assumption behind the stress-coping viewpoint on alcohol and drug problems in the family is that a serious drinking or drug problem can be highly stressful both for the person whose drinking or drug taking constitutes a problem (the ‘relative’) and for anyone who is a close family member (the ‘family member’). This is because serious drinking or drug problems are, by their very nature, associated with a number of characteristics which are very damaging to intimate relationships and can be extremely unpleasant to live with. Such problems frequently continue unabated, often intensifying, over a period of years and are appropriately construed as long-standing stressful conditions for family members. This model views family members as being at risk of strain, in the form of symptoms of physical and/or mental ill health, as a direct consequence of the chronic stress occasioned by living with a relative with a drinking or drug problem.

A central assumption is that family members are then faced with the large and difficult life task, involving mental struggle and many dilemmas, of how to understand what is going wrong in the family and what to do about it. In particular, this task includes the core dilemma of how to respond to the relative whose drinking or drug-taking behaviour is seen as a problem. The ways of understanding reached by the family member at a particular point in time, and her (or his) ways of responding, are what are referred to collectively as ‘coping’ (‘responding’, ‘reacting’ and ‘managing’ are synonyms). The word is certainly not limited to well-thought-out and articulated strategies. It includes ways of understanding or responding that the family member believes to be effective as well as those judged to be ineffective. It includes feelings (for example, anger or hope), tactics tried once or twice and quickly abandoned (such as trying to shame the relative by getting drunk oneself), philosophical positions reached (e.g. ‘I’ve got to stand by him because nobody else will’), and ‘stands’ taken (e.g. ‘I’m not coming back until …’).

Figure 1.1 The stress-strain-coping-support model.

A further assumption about coping with a relative’s excessive drinking or drug taking is that some ways of coping are found by family members to be more effective than others. The word ‘effective’ is being used in two senses here. First, family members may find some ways of responding to be more productive than others in buffering the effects of stress and hence preventing or reducing the strain they themselves experience (or which other members of the family, children for example, experience). Second, family members may find some ways of managing the problem to be relatively effective and others relatively counter-productive in having a desired effect upon the relative’s drinking or drug taking. It should be emphasised here that it is an assumption of the stress-coping model that family members can have an impact on their relatives’ substance use in both desired and undesired directions. In other words, family members do have some potential for influencing their relatives; they are not totally powerless. That is an important assumption and one which distinguishes the stress-coping model from some other perspectives on the subject.

The model is completed with the assumption that social support is a powerful factor with potential to mitigate the effects of stress on health. By the same token, unsupportive behaviour can further exacerbate the stresses and strains that the family member experiences. Support, it is assumed, can come from many directions, and certainly includes both kin and non-kin informal sources as well as more formal sources offering professional services or self-help.

Note should be taken that the stress-coping viewpoint makes the assumption that there are such things as ‘drinking problems’ or ‘drug problems’ and that it is individuals (the people we refer to as the ‘relatives’) who have such problems. Although in this book we generally avoid terms such as ‘alcoholism’ or ‘drug addiction’ (although family members often use such terms), preferring the more general ‘problem’ or ‘excessive’ drinking or drug taking, the stress-strain-coping-support model is one that takes such problems very seriously indeed. It assumes that such problems generally represent disasters for families and represent serious hazards to the health and happiness of family members as well as their relatives. Family members, like the relatives they are concerned about, are victims of an uninvited and unwanted hazard. As we shall see, not all perspectives take that line.

Family pathology models

Much of the professional and academic literature on alcohol and drug problems and the family has adopted a very different position. Starting with writings about wives of ‘alcoholics’ in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, family members of relatives with drinking or drug problems have very often been viewed as individuals who were part of the problem themselves. They have been seen as suffering themselves from forms of ‘psychopathology’, and as people who have their own needs that are satisfied by living with someone who drinks or takes drugs excessively. The family pathology perspective has been quite influential in the past, and, as we shall see, it continues in various guises to be very influential still. It is important therefore that we be aware of it and examine it closely.

The psychopathology of alcoholics’ wives was described by a number of early authors (e.g. Price, 1945; Bullock and Mudd, 1959) but Whalen’s (1953) single conttibution was one of the most outspoken and most quoted in the years that followed. The following extract makes the contrast with the stress-coping view abundantly clear:

The woman who marries an alcoholic … is usually viewed by the community as a helpless victim of circumstance. She sees herself and other people see her as someone who, through no fault of her own and in spite of consistent effort on her part, is defeated over and over again by her husband’s irresponsible behaviour. This is certainly not true. It merely appears to be true. The wife of an alcoholic is not simply the object of mistreatment in a situation which she had no part in creating. Her personality was just as responsible for the making of this marriage as her husband’s was; and in the sordid sequence of marital misery which follows, she is not an innocent bystander. She is an active participant in the creation of the problems which ensue.

(p. 634)

Whalen proceeded to outline four personality types which she considered were frequently found among wives of alcoholics, although she stressed that other types existed also. The first, Suffering Susan, displayed a need to punish herself as a dominating characteristic: ‘she chose a marriage partner who was obviously so troublesome that her need to be miserable would always be gratified’ (p. 634). The second, Controlling Catherine, dominated every aspect of the marital relationship. She had no doubt that she was the more capable of the two at making decisions and she controlled the family purse strings. Marriage was a vehicle for expressing her distrustful and resentful attitudes toward men in general. The third, Wavering Winifred, might separate from her husband for a few weeks but always returned when he pleaded. Her behaviour changed as much as his did; when he was drunk, she was furious and despairing, but when he was sober, she regained her good spirits and forgave the past. She had chosen a husband who ‘needs her’ (p. 638). Finally, Punitive Polly behaved toward her husband like a scolding but indulgent mother. She was often a career woman and might well earn most of the family living or else be responsible for getting the husband his job or obtaining contracts for him. Her relationships with other people, especially men, were characterised by rivalry, aggression and envy, and she had chosen a husband who was often several years her junior or who was limited in his masculinity in some way.

Those who wrote in that way in that era stressed the variation to be found among the personalities of wives married to men with drinking problems. Pattison et al. (1965) also described a range of ‘character pathology’ among wives of alcoholics, including the ‘masochist’ type, ‘the hostile hysteric’, ‘the symbiotic dependant’ and ‘the maternal’. Some writers (e.g. Rae and Forbes, 1966) did acknowledge that most wives of men with alcohol problems showed elevated anxiety and depression which might be attributable to stress, but they believed that a definite minority displayed some form of ‘character disorder’.

The view that wives actively contributed to their husbands’ drinking problem was said to be supported by a number of observations. One was that many women married in the knowledge that their husbands drank excessively (e.g. Lemert, 1960; Rae and Forbes, 1966). Another was that wives had negative perceptions of their husbands whether or not the latter were sober or drinking, and even when they gave up drinking altogether. For example, Macdonald (1956) stated, ‘Many … women … are able to tolerate a marital relationship only with a non-threatening type of partner who they can subtly depreciate in a variety of ways, and an alcoholic may frequently meet those requirements.’ Yet another observation, frequently backed up by anecdotal accounts of wives encouraging their husbands to return to drinking after an attempt at treatment (e.g. Rae and Forbes, 1966), was that wives discouraged their husbands’ sobriety even to the point of attempting to undo the latter’s attempts at change. For example, Ballard (1959) stated that, ‘in spite of her protestations to the contrary the wife has an appreciable stake in maintaining the status quo’. Bailey (1961) in her review remarked that clinical observations of wives sometimes fighting their husbands’ attempts to obtain help and appearing to have a vested interest in keeping their husbands actively alcoholic had evolved into one of the most frequently cited descriptions of ‘the alcoholic’s wife’. A related observation, much cited in writings of the wives’ psychopathology school at that time, was the tendency of wives to become more distressed (or to ‘decompensate’) if and when their husbands became dry (e.g. Futterman, 1953; Igersheimer, 1959).

Many such observations were difficult to prove or disprove, and were often a matter of interpretation: for example, how much a prospective wife might know about her husband’s drinking at the time of marriage, to what extent it fitted social conventions, and how at that time she might view his future drinking. Very little convincing research was carried out on these questions. Evidence has largely been against the decompensation hypothesis, suggesting rather that family members are less distressed when relatives give up drinking excessively (Moos et al., 1990). Although some of these ‘pathology’ notions are now of historical interest, the underlying idea that family members contribute to the problem has not gone away.

One observation which remains particularly pertinent half a century later was that wives were reluctant to become engaged in treatment. It was of course expected by those who supported the family pathology model that wives ought to engage in treatment aimed at their own personal change rather than simply counselling on account of stress experienced as a result of living with someone with a drinking problem. The resistance of wives to these treatment efforts was a frequently occurring theme, and much discussion revolved around the question of the wife’s responsibility. For example, Price (1945) considered that only three of 20 wives of alcoholics studied were ready to see that they themselves bore any responsibility in the situation. Macdonald (1958) also referred to the difficulties encountered in running an analytic group therapy programme for wives. A high drop-out rate and the wives’ criticism of the unstructured nature of the groups were referred to, as well as the wives’ general lack of interest in gaining insight. This was interpreted as reflecting resistance to change. It was Igersheimer’s (1959) opinion that ‘only occasionally does a non-alcoholic wife wish to search within herself for attitudes and feelings which might contribute to her husband’s drinking. Generally speaking these wives are relatively refractory to intensive individual insight therapy.’ But again Whalen’s (1953) contribution was outstandingly frank on the matter:

when we get an application from one of these women, we listen carefully to her complaints … [which] come to a focus on her basic concern … her anxiety about herself.… at this point … the counsellor says something like … ‘Yes, it is clear to me that your husband’s drinking creates many difficulties for you. But I can also see that you yourself have a problem which also contributes to your difficulties. It is this problem of yours which we can offer you help with if you want to work on it.’ This is a challenging statement and one to which they respond variously in terms of their individual personalities.

(p. 633)

In the past it has mostly been wives of men with drinking problems who have been the focus of family pathology models (as we shall see in Chapter 2, there has been much less focus on husbands of women with drinking problems, and there has been none on gay and lesbian partners). As attention has turned in the last few decades to drug misuse by adolescents and young adults, it turns out that the dominant perspective on the family within the academic and professional literature has also been one of family deficiency and pathology, but this time it is parents who have been the focus. Reviews of research and expert opinion on the subject typically take the form of a catalogue of failures and dysfunctions on the part of parents that, it is assumed, have contributed to a young person’s drug misuse. Many examples could be cited but two will suffice. One is the extensive background section to a paper by Jurich et al. (1985) comparing the perceptions of their families held by ‘drug abusers’ and infrequent or occasional drug users. The second is from a monograph on a therapeutic community for drug addicts in the Netherlands, which, to its credit, took great steps to involve families in its work (Kooyman, 1993).

The long list of family deficiencies given by Jurich et al. included the following: a broken home, father absence, lack of closeness, parental immaturity and inability to adapt to changing situations, poor communication and mutual misunderstanding, lack of family coping skills, laissez-faire discipline, authoritarian discipline, parental ‘alcoholism’, and parental drug use. Kooyman’s list included over-involved, overprotective parenting; detached, neglectful parenting; paternal drinking problem; traumatic family experiences, including violence, child molesting, incest, suicide, psychiatric admission, sudden death, and separation; parents rarely rewarding acceptable behaviour; anger or criticism rarely being expressed directly; unclear boundaries between the generations; and a strong mother–child and weak father–child relationship. One family pattern, described as ‘neurosis’, involved, according to Kooyman, an intense conflict in the family around the drug addict, weakness of boundaries in the family hierarchy, a polarity between the addict as a ‘bad’ child and another ‘good’ child, contradictory communications in the family, and explosive and violent conflicts. Clark et al. (1998) acknowledged the possibility that deficits in family functioning might be, at least in part, a consequence of the substa...