- 428 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Merely to inhabit a desert demands much skill, craft, experience and travel. For the numerous nomadic tribes of Africa and the Middle East, living ancestors of the Egyptians, Jews and Arabs, Egypt is their meeting ground. The author, with twenty-five years of accumulated knowledge, here sets out to present analyses of their cultures and beliefs, along with descriptions of each tribe.

First published 1935.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sons of Ishmael (RLE Egypt) by G.W. Murray in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Regional Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

CHAPTER I

THE DESERT IN ANCIENT TIMES

“I hold rather that the Egyptians did not come into being with the making of that which Ionians call the Delta; they ever existed since men were first made; and as the land grew in extent many of them spread down over it, and many stayed behind.”–Herodotus.

The Desiccation–Hamitic Africa–The “Troglodytes”–Early Semitic Arrivals–The Pharaohs' Hunt for Gold–The Hyksos–The Hebrews–The Libyan Invasion–Ptolemaic Trade Routes–Roman Patrols–Nature of the Northern Littoral–The Blemmyes–The Arab contrasted with the African Bedouin.

“Happy are those nations that have no history,” and history in the desert does not gallop, but crawls at a camel's pace. Whole centuries pass without events. Yet to those who can wait long enough things happen even in the desert, and if we accelerate our magic carpet sufficiently in time, more may be seen than an interminable series of petty raids for camels.

For climate is subject to variations, periodic rather than annual, and round a desert which is not absolutely sterile, a succession of only two or three years with rain may produce alarming consequences. Then the neighbouring cultivators are suddenly assailed by vast clouds of locusts, immeasurably more numerous than the trivial swarms of the year before, and, in a twinkling, ruin takes the place of plenty. A far more dangerous situation comes about when a generation of good years is succeeded by a period of drought. Sooner or later an explosion, only to be likened to that of a volcano, results and the desert discharges floods, not indeed of lava, but of fierce nomads not to be withstood by anything less than the strength of a militant civilization.

Such a vent of racial dispersion exists in the Arabian peninsula, dormant for the moment, and the former existence of others in the Sahara may be inferred from the widespread litter of Hamitic languages and cults which they have spewed all over Africa. (Indeed, until quite lately, the “Green Mountain” (Jebel Akhdar) behind Derna in Cyrenaica represented a pretty active little crater of this kind).

Northern Egypt must then have resembled the present Negeb of Southern Palestine, where chalky hills covered with dwarf oak and scrub rise from broad plains of alluvium, rich with grass after the winter rain, but in summer, dry, dusty, and subject to aerial erosion.

In Southern Egypt the limestone gives place to sandstone, and here, in Palæolithic and Neolithic days, a great natural frontier ran right across Africa, busy with “factories” where the more fortunate flint-owning races of Middle Egypt and Cyrenaica probably traded hand-axes and scrapers with the even less civilized tribes of Nubia and Inner Libya.

Ten to fifteen thousand years ago, rain very gradually ceased to fall on the low-lying parts away from the coasts, desert conditions began to spread little by little and presently, urged by the north-westerly gales, the long parallel lines of dunes which now streak the Libyan Desert set out on their long march from the Qattara Swamps to the oases at a glacier-crawl of less than ten yards a year.

East and west of the Nile, the grass and scrub slowly vanished, the trees withered, the game migrated, and the cattlemen and hunters deserted the drying plains for the marshes of the Nile Valley, which until then they had looked upon as rather dangerously full of elephants, lions, and the like.

The last desert areas to be abandoned were, curiously enough, those most inaccessible to-day–the sheets and rolling dunes of sand which, unlike the gravel, retained something of the scanty rainfall.1 These are dotted to-dav with the grinding stones and spearheads left by the men of the past.

Down in the valley they took to cultivation and fishing, and were soon cankered with the beginnings of civilization. For the noble and lazy nomad may turn into an industrious fellah, but he can never turn back. Hardihood to support starvation, thirst, the fatigue of travel, the hammer-blows of the sun, the blasts of the sandstorm is not acquired in one but many generations. The Bedouins of to-day are the unspoilt descendants of Ishmael; their blood is pure.

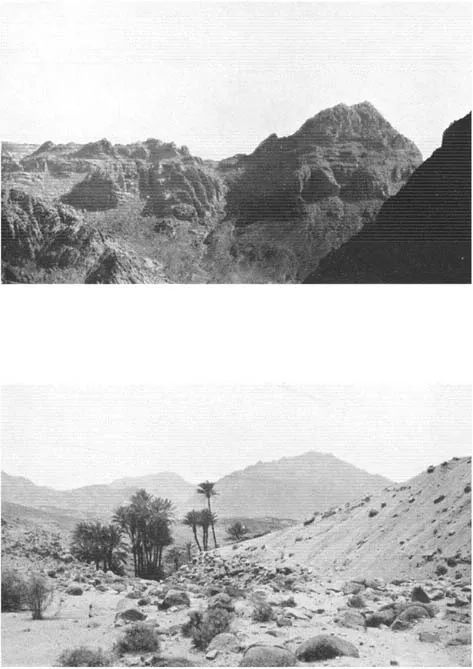

PLATE I

Wadi Gharba

SINAI SCENERY

So the upland plains were abandoned to the wind, now laden with sand, which soon removed every vestige of soil from the surface. Only such mammals as were adapted to rainless conditions remained: the wild ass, gazelle, ibex, Barbary sheep, addax and oryx antelope, ostrich, and cheetah. All these, except perhaps the oryx, survived to within human memory; while the giraffe, which can live several months without drinking, visited the southern deserts in good years. The leopard, a hill-animal, is gone from Egypt, but haunts the mountain peaks of Sinai.

Some remnants of this former abundant Saharan fauna lingered long; the elephant survived in the Atlas till Roman times and dwarf crocodiles are still found from time to time in the wadis of Air and Ahaggar. Fish of the genus Cyprinodon occur in the Khor Arba‘at near Port Sudan, the lakes of Siwa Oasis, and, in Algeria, in the oasis of Zab and the Wadi Gir. I have seen toads in the Egyptian oases and also in Jebel Asotriba just south of the Egypto-Sudan frontier.

Some early rock-drawings of elephants near Aswan have been weathered to the same colour as the rock on which they were hammered out and may perhaps date back to a wetter period.1 But after the final setting-in of the great drought, there is abundant proof that the climate of Egypt has remained virtually unchanged throughout the whole historic period. For, near Aswan in the same region as the rock-drawings mentioned above, the Archaeological Survey of Nubia discovered pre-dynastic bodies perfectly preserved by the dry sand alone without artificial aids, while in Sinai the First Dynasty inscription of Semerkhet at Jebel Maghara (in very soft sandstone) “does not appear in the least weathered since it was cut”. These relics of the past would not have come down to us at all, if there had been regular rainfall at any time during the last five thousand years. Again in the days of Rameses II, a lack of water in the desert led to the temporary abandonment of the gold-mines; while to make another great leap through the centuries, Strabo records as a marvel “that it rained in Upper Egypt in his time”.

Until the completion of this desiccation, so remote in time by ordinary standards, though really quite late in the long history of the human race, the whole of North Africa with the Arabian peninsula must have formed one great grassland or steppe, roamed over by intensely nomadic families of hunters and herdsmen following the rainfall like the animals they tamed or slew.

Even at this early stage, they could not have been wholly homogeneous; the more active plainsmen must have soon become differentiated from the stay-at-home mountainfolk, just as elsewhere the ship-owning people sailed right away into a different culture from the timid fish-eaters of the coast. But most of their skulls exhibit an extreme dolichocephaly, and all their languages which survive to-day are of the same type, Hamitic. Of this, the Semitic family, important as it is, seems to be only a later specialized group.

With the gradual intensification of the drought, their mass movements became more and more restricted, and the tribes began to solidify into races; while the hardening of the conditions under which they lived so sharpened their wits, that the progressive families, who settled in the rich valleys hitherto avoided on account of the wild beasts they contained, soon began to cultivate.

Two racial groups began to form; the “Arabs”, isolated between the Nile and the Euphrates, who had been influenced by the “Armenoids”, a hook-nosed race from the north-east, and the “Libyans” of the Sahara who became tinged to a darker hue with negro blood in the south, and whitened along the coast as the result of European inroads.1

Everywhere some of the more conservative, inspired with a native distrust of the nascent civilizations of the valleys and a deepseated passion for personal liberty, coupled with a contempt for any possessions that might hamper their freedom, held to the high desert at all costs, where their equally conservative descendants of to-day still attempt the simple life of their forefathers. They were not yet in possession of the camel, but if their humble ass was not exactly a ship of the desert, he was certainly a most serviceable beast. “Donkeys and determination” had to be their motto, and, since the donkey is not an animal on which to carry out raids, they must perforce have abstained from the organized plunder of their more industrious neighbours. Later on, when the horse came in, the Egyptian quadrilateral became a desert stronghold, protected on the north by the wellnigh impregnable Delta, on the east by the Red Sea, and on the west by the dunes. Certainly it was open to invasion from the Sudan down the Nile, yet the gateway there is so well guarded by art and nature that it has only once been forced–in the twenty-fifth Dynasty. But, however strong its walls, this Egyptian fortress was exposed at every corner to bold raids from the hills beyond the desert.

At different times, Libyans burst in upon the Nile Valley from the “Green Mountain” in Cyrenaica; Nubians from the hills of Darfur took possession of the cataracts; while wave upon wave of Ethiopians chased each other north-westwards from the mountains of Abyssinia. All these were North African races, even if mixed with foreign blood, and their raids and incursions made little physical and cultural difference. But the foreign invasions from the north-east were of vastly greater importance. All Egypt fell a prey to the Hyksos at the end of the Twelfth Dynasty; while in the seventh century of the Christian era, the Arabs made a lasting conquest and stamped their language and religion not only upon Egypt, but upon all North Africa.

The neolithic ancestors of the Egyptians left nothing behind them on the surface but their implements of stone, wrought from chert and flint in the north; from quartz, quartzite, sandstone, slate, and various igneous rocks in the south. West of the Nile, rock-paintings discovered by Count Almasy at Jebel ‘Uweinat, show a chocolate-coloured race, with a taste for steatopygy in their women, owning cattle and armed with the bow. The climate of ‘Uweinat must have permitted their survival down to dynastic times, for one of the chiefs is depicted smiting his enemy in true Pharaonic style. Yet Miss Caton Thompson found no trace of dynastic remains in Kharga prior to the twenty-seventh Dynasty.1

East of the Nile in the Red Sea hills, a scanty rainfall has enabled a race resembling the pre-dynastic Egy...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Haft Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Preface

- THE BAD PENNIES

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

- Works Frequently Cited

- Introduction

- PART I

- PART II

- PART III

- PART IV

- APPENDIX WESTERN DESERT LAW

- INDEX