- 152 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Primer on Environmental Policy Design

About this book

Discusses how the needs of the individual must be balanced with socially desirable ecological goals if the environment is to be protected.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Primer on Environmental Policy Design by R. Hahn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

A Primer on Environmental Policy Design

ROBERT W. HAHN

Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and Council of Economic Advisers, Executive Office of the President, Washington, D.C.

1. INTRODUCTION

As a child, I was briefly influenced by the recycling “movement” that had achieved some degree of popularity in middle class suburbs throughout America during the late sixties. Many people were concerned that too little attention was being given to the environment around us. To join the vanguard, I asked my parents to recycle bottles and aluminum cans at the local recycling center. Initially, things worked quite well from my point of view. My sister and I would put the bottles and cans into plastic bags and accompany my father on a trip to the center, which was located by the beach. As time went by, however, I must confess that my enthusiasm waned, and I lost interest in recycling. My initial response was to urge my father to continue while I pursued other more worldly pleasures such as basketball. For a while, this strategy worked, but eventually my father decided to pursue his worldly vice, which was (and still is) golf. At some point, I noticed that Dad was not taking recycling seriously anymore, and mentioned this fact to him in what must have been an obnoxious manner. His response, which I will never forget, was “Ecology starts in the home—clean up your room.” And thus began my career as a student of environmental science and policy.

The lessons from my experience as a child have had a great impact on the way I think about environmental policy. Most importantly, I learned the importance of motivation and staying power. As the initial excitement over the recycling movement was replaced by the drudgery of transporting cans, it became clear to me that my contribution to solving the problem was really only a drop in the bucket. That wouldn’t have mattered to me much if there were something there to keep my continued interest, but there wasn’t. That was a very important lesson. I learned that the system of economic and social rewards associated with a policy can have a major impact on how a person behaves in different situations. Finally, there was the unforgettable response of my father, who was obviously fed up with the whole ordeal. That taught me that people often have divergent interests, and will go to great lengths to move policy in a direction that will be useful for them.

The trick would appear to be to design ways to achieve socially desirable goals while allowing people to pursue their individual self-interest. This is no small feat. My objective in this book is to examine approaches to this problem in designing environmental policy. The framework for the book builds on the disciplines of political science and economics. Both disciplines are unified in their focus on the self-interest of the individual. Political science focuses on the activities of individuals in the political sphere. Economics focuses on the interests of individuals in managing their own resources. In reality, the two problems are inseparable. Politics can have a significant impact on the opportunities available to an individual to pursue economic gain. Thus, it makes sense to integrate the two notions of self-interest under a single roof. This, in essence, is what political economy is all about.

This book is an attempt to integrate our economic understanding of environmental policies with our understanding of political institutions. To my knowledge this is the first attempt to do so in a volume which reflects the current state-of-the-art in both of these disciplines. Section 2 provides an overview of environmental policies, and also examines the basic frameworks used by economists and political scientists to address environmental problems. Actual experience in the use of new approaches to environmental management is chronicled in Section 3. The section focuses on the actual application of emission fees and marketable permits, two instruments that have received widespread support from economists. Section 4 offers some explanations for a variety of patterns that are observed in environmental regulation. The problem of designing systems that improve environmental quality and increase productivity is addressed in Section 5 in the context of a particular pollution problem. The case study, which identifies new approaches for helping to meet the current U.S. ozone standard, is helpful in identifying how general insights about the performance of regulatory systems can be applied to specific problems. Finally, Section 6 highlights the principal conclusions and suggests areas for future research.

2. FRAMEWORKS FOR ANALYZING ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY

2.1. Introduction

Public concern over environmental issues has risen dramatically over the last two decades. There has been increasing pressure on the governments of industrialized countries to develop a reasoned response to a variety of problems, such as acid rain, the clean-up of toxic waste dumps and urban air pollution. The people in charge of developing and administering these control programs face a gargantuan task. To help make this task more manageable, policy analysts have developed a series of models for understanding the implications of pursuing different environmental control strategies. The purpose of this section is to provide an overview of selected environmental approaches to problem solving and to suggest frameworks for evaluating and understanding these approaches.

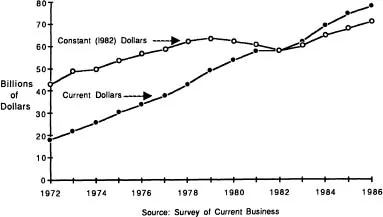

The primary aim of this book will be to serve as an aid in the design of less costly, and more effective, policies for addressing environmental problems. If the need for identifying such policies is not self-evident, a review of environmental expenditures over time helps to provide a rationale. Figure 1 lists pollution control expenditures in the United States from 1972 to 1986 (Farber and Rutledge, 1986, 1987). Nominal expenditures have risen dramatically over this period from $18 billion to $78 billion. Real expenditures have also increased by over 60 percent during this period. Currently, about 2 percent of the entire gross national product is used to address environmental problems. Expenditures will probably continue to rise for the foreseeable future. Heightened concern over a variety of problems ranging from the depletion of stratospheric ozone to the generation and disposal of hazardous wastes will give rise to regulations with very sobering price tags. For example, a reauthorization bill proposed for cleaning up hazardous waste in the U.S. would cost taxpayers $9 billion (Wall Street Journal, 1986).

FIGURE 1 U.S. Pollution Control Expenditures

Simply stated, the central issue addressed in this book is whether it is possible to get more for less. While apparently a simple question, it defies a simple answer. In theory, it is often easy to design systems that will give you “more bang for your buck.” The real world is quite another story, however. In most cases, executing policies in the real world is much more complex than theory admits. Moreover, there are frequently very strong political forces that constrain what can and cannot be done.

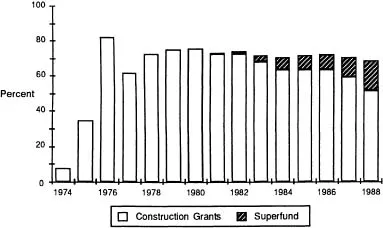

One measure of the strength of political forces is the fraction of expenditures that are earmarked for pet projects of Congressmen (i.e., “pork barrel” projects). The precise definition of such projects is always problematic. Two programs that are thought to have a large pork barrel component are the Construction Grants Program and Superfund (Arnold, 1979; Smith, 1986). The Construction Grants Program is used to help finance sewage treatment plants. Superfund is used to help clean up old hazardous waste sites, many of which have been abandoned. Figure 2 shows the percentage of EPA funds allocated to both of these programs. In 11 of the last 13 years, these two programs accounted for over 70 percent of the total EPA budget, with the lion’s share going to Construction Grants. In the future, this balance can be expected to change as Superfund gains increasing support. The figure provides striking testimony to the fact that much of environmental policy has its roots in electoral politics.

Source: Office of Management and Budget

FIGURE 2 Construction Grants and Superfund as a Percentage of EPA Budget

Because politics has a strong impact on the shape of environmental policy, it should come as no surprise that programs are rarely designed with economic efficiency as a primary goal. For many years, economists have argued that it is indeed possible to get more for less by placing greater reliance on the use of economc incentive mechanisms in protecting the environment. While many of these arguments were compelling in theory, they lacked the force that practical examples can offer. As we shall see in Section 3, a review of practical experience reveals that economic applications deviate dramatically from standard textbook discussions of these approaches. Nonetheless, in certain situations, approaches based on economic theories have had dramatic effects on efficiency. Moreover, economic theory can serve as a useful guidepost for evaluating current policies.

The fact that policies deviate from some of the idealized visions of economists is not particularly surprising to students of politics. Economists represent but one of many interest groups that have tried to influence environmental problem solving. In many cases, the interests of economists diverge from other more powerful interest groups represented by regulators, business interests and environmental lobbies. The challenge for political science is to try to explain the current configuration of policies on the basis of political institutions and the interests of key actors in the policy making process. One of the objectives of this book will be to extend our understanding of the forces that shape environmental policy by applying some basic concepts used in political science.

A useful starting point for developing more effective policy is to characterize normative frameworks that allow us to compare the performance of different approaches. This is done in part 2.2 of this Section. Part 2.3 then provides an overview of various policy instruments and examines their theoretical performance characteristics. The political motivations of regulators and legislators for choosing various policies are explored in part 2.4. Finally, part 2.5 summarizes the key ideas presented in the chapter.

2.2. The Normative Framework

The focus of this book will be on designing policies that have the potential to meet environmental objectives in a more timely and efficient manner. Frameworks can be useful as a tool for helping to guide design. Two basic frameworks will be employed here. The first, borrowed from welfare economics, is normative. It provides measures for evaluating the efficiency and effectiveness of different policies. The second, borrowed from political science, is positive. It identifies key factors that affect how policies are implemented and which policies are likely to be feasible.

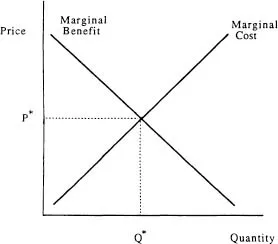

The basic normative framework used in applied welfare economics is designed to help examine the relative efficiency of different policies. The hallmark of the normative approach is to specify a desired objective. A typical objective is to identify policies that maximize net benefits. An efficient policy is defined as one which maximizes net benefits. This idea is illustrated in Figure 3, which shows the marginal costs and benefits associated with various levels of pollution abatement. When marginal benefit and cost curves are well-behaved, as shown in the figure, the problem is to identify the point (P*, Q*) and then identify control strategies accordingly. While this paradigm provides a useful starting point, it is usually difficult to implement in a straightforward manner. There are great uncertainties in identifying marginal benefits and costs.

FIGURE 3 The Standard Paradigm in Microeconomics

To understand the importance of uncertainty in this formulation of the problem, it is instructive to examine the origins of the marginal benefit and the marginal cost curves shown in Figure 3.1 For environmental policy problems, analysis of the net benefits of control requires estimating both the benefits and costs of control as a function of the quantity of emissions of various pollutants. The first step in the analysis is to identify which pollutants to control. The answer may be clear, as in situations where a chemically inert pollutant is emitted from a single “pipe” into an isolated environmental reservoir (some lakes, for example). In other cases, numerous sources emit complex mixtures of reactive species into nonisolated airsheds and watersheds. The acid deposition and urban ozone problems are examples of these latter cases, for which the question of which agents to control has not been definitively answered.

Once the chemical agents that contribute to the problem have been identified, estimates of pollution control costs can either be obtained directly from engineering estimates or indirectly from estimated production functions. Both techniques have strengths and weaknesses. Engineering estimates typically provide detailed estimates of pollution control options, but little information on the uncertainty associated with such estimates. Moreover, they rarely consider detailed process changes that could arise. Production function estimation, as it is typically applied in econometrics, tends to focus more on the aggregate relationship between inputs and outputs, treating the production process as a “black box.” This estimation procedure provides estimates of the error associated with various parameters. However, such estimates may be of dubious value if the model does not adequately capture the structural relationship between inputs and outputs.

Estimation of the marginal benefits of different control strategies usually involves two steps: the first is the determination of the effect of the controls on environmental quality, and the second is the evaluation of the benefits that accrue from incremental changes in environmental quality. There are usually large uncertainties associated with both steps. For example, consider the problem of controlling acid deposition. The control measure usually suggested for reducing acid deposition is reduction of emissions of sulfur oxides from power plants and other industrial sources. The chemical and physical processes that occur between emission and deposition of sulfur species makes it difficult to accurately predict how much a given level of emissions control will reduce deposition. The pollutants may undergo both gas-phase and aqueous-phase chemical reactions, and be transported over distances up to hundreds of kilometers. Some of the chemical steps, especially those occurring in clouds, are not well understood (National Academy of Sciences, 1983). The meteorological conditions that affect both chemical transformations and physical transport of the pollutants vary from day-to-day and year-to-year, contributing to the uncertainty in estimates of the relationship between deposition and emissions control. Finally, just measuring the amount of sulfur that has deposited on various surfaces has proved to be an extremely difficult task.

Placing a dollar value on the damages associated with acid deposition is even more problematic. Benefits estimation is an inexact science at best. A variety of techniques are used to estimate the dollar value of changes in control levels. For example, in the case of materials damage to buildings, some estimates of the increased costs associated with maintaining buildings or using different construction materials may be used. To assess the effect that acid rain has on lakes and recreational fishing, survey data are used to estimate the opportunity cost of fishing in other lakes. In instances where acid deposition is thought to affect human health, regression models may be used to infer the increase or decrease in morbidity and mortality. These numbers then need to be converted into dollar values. It should be quite apparent from this brief examination of the acid deposition problem that the development of benefits techniques is still in its infancy. Virtually all existing benefits techniques are characterized by large uncertainties, sometimes involving several orders of magnitude (Freeman, 1979).

The question naturally arises as to how to deal with these uncertainties. Uncertainty in the nature of the problem needs to be dealt with by selecting policy instruments that are flexible. By defining policies in a way that allows them to accommodate changes in our understanding of the underlying science, resources can be saved (Hahn and Noll, 1982a, 1982b). Another way of saving resources is to design systems that provide firms greater flexibility in their choice of abatement options for meeting prescribed objectives.

Because of difficulties in estimating benefits, economists often compare policies in terms of their cost-effectiveness. A cost-effective policy is one which meets a prescribed objective at the lowest possible cost. In the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Orginal Copyright Page

- CONTENTS

- Introduction to the Series

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Frameworks for Analyzing Environmental Policy

- 3. Economic Prescriptions for Environmental Problems: Not Exactly What the Doctor Ordered

- 4. The Political Economy of Environmental Regulation: Towards a Unifying Framework

- 5. Towards Usable Knowledge: An Exercise in Designing New Regulatory Approaches

- 6. Whither Environmental Regulation?

- Appendix

- References

- Index