![]()

1 Introduction

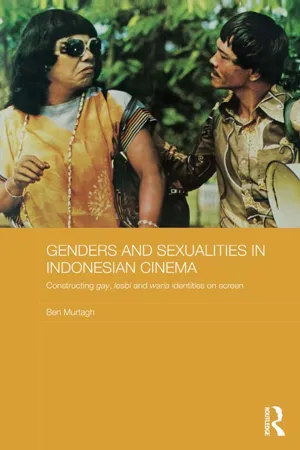

I began to think about representations of gay, lesbi and waria (male to female transvestite) Indonesians in film when working on my doctoral thesis.1 As I struggled in London with my study of traditional Malay literature, the 2003 release of Nia Dinata’s Arisan!, a film which apparently included Indonesia’s first cinematic gay kiss, became an international news story. Following the lead of those brief reports, and as a diversion from my thesis, I began to look into the history of constructions of homosexuality in Indonesian cinema. This task was facilitated by a privileged access to what I discovered to be a remarkable collection of Indonesian films held by SOAS library. That project culminates in the publication of this book.

As a British gay male researcher who identifies with the perhaps somewhat old-fashioned label of Indonesianist, my reasons for being interested in alternative sexualities in that archipelagic nation are probably obvious. Since I first visited Indonesia in 1990 I have been intrigued by the lives of gay, lesbi and waria Indonesians and the stories that they have to tell. However, more often in my travels I came across stories and narratives about gay, lesbi and waria Indonesians, told by people who often wished to warn me of the immorality of homosexuality. I do not think these people ever imagined that I might be gay, and I often did not feel secure enough to inform them otherwise. This position of silence ensured that I was frequently the audience to an often prejudiced and ignorant perspective which I might not have heard otherwise. The more I came to know gay and waria Indonesians, the more I realized how poorly those stories reflected the diversity of lived experiences of Indonesia’s sexual minorities. Stories about gay, lesbi and waria Indonesians come in various forms and are told in a range of media. They are listened to by passengers in taxis, and groups of friends in coffee shops. They are read by housewives and their husbands in women’s magazines, and by all manner of individuals in short stories published in newspapers. Young people in bookstores furtively dip into recently published queer anthologies. Stories are also watched on cinema, television and computer screens. The aim of this book is to explore one specific collection of those stories: those that have been told through the medium of what may loosely be described as mainstream Indonesian cinema.

Cinema in Indonesia has a history which stretches back to the beginning of the twentieth century when the first moving pictures arrived in the country. Until the Japanese occupation, filmmaking in the Dutch East Indies, as it was then known, was mainly in the hands of the Dutch and ethnic Chinese.2 With independence following the Japanese defeat, Indonesians began making films, and annual local production rose to 58 films by 1955 (Sen 1994: 19), though the number of foreign imports, mainly from the United States and India, always far outweighed national production. Filmmaking during the Sukarno period (1945–66) was notable for its nationalist concerns, and, reflecting political developments post-1956, for the increasing influence of leftist cultural organizations. Following the dramatic events of the night of 30 September 1965, which led to the fall of Sukarno and the establishment of the New Order regime of President Suharto (1966–98), almost all of the films made by directors associated with LEKRA, the Institute of People’s Culture, were lost or destroyed, and filmmakers and technicians were detained without trial. As Sen remarks, ‘any analysis of New Order cinema needs to take into account the traditions of filmic practice it inherited and those which it lost in the decimation of the leftist cultural movement’ (1994: 37). However, I am not aware of any films from this period which would be pertinent to the subject of this book.3

Given the upheaval and chaos of 1965–6, the New Order period saw a transformation in the institutions of cinema and these have been explored in depth by Krishna Sen in her 1994 book Indonesian Cinema: framing the New Order. By 1971 local production of films rose to 52, and peaked at 124 films in 1977. The 1980s saw production of at least 50 films per year with another peak of 101 films in 1989 (Heider 1991: 19). In the 1990s production began to decline in numbers and quality as many involved in the industry moved over to television as a result of substantial changes in the media industries. The economic crisis of 1997–8 brought filmmaking to a state of near collapse. The range of films made during the New Order is wide, though strict censorship clearly impacted not just on the final products but also on who was allowed to produce films. A glance through Kristanto’s catalogue of Indonesian film (2007) shows that in addition to the more serious and artistic works by filmmakers such as Eros Djarot, Garin Nugroho, Teguh Karya and Ami Prijono, large numbers of more popular films were being produced in genres such as comedy, mystical/martial arts, teenage movies, melodramas and increasingly by the end of the New Order period, soft-core erotic films. Sen cites figures which show that in 1984 the largest audience segment was in the 15–24 age range, and during the 1980s annual film audiences were around 130 million, having peaked in 1980 at 144 million (1994: 71). Jakarta’s share of the total audience was around 20–25 per cent in the 1970s and around 16 per cent in the late 1980s. It seems that national films were watched by 30–40 per cent of viewers overall in the 1980s (Sen 1994: 71). It is during this period that waria, lesbi and gay characters first appeared in Indonesian cinema. Excluding the minor comedic waria and cross-dressing characters that routinely appear in many slapstick comedies, at least 30 films made during this period include characters that might be readily recognized as of non-normative gender or sexuality by Indonesian audiences. I analyse films from the 1970s to 1990s from a range of genres including teenage films, comedies and melodrama.

Since the fall of Suharto’s New Order regime in 1998, Indonesian film production has undergone something of a rebirth. By 2007 annual production had risen to 78 films, four of which gained audiences of over one million (Widjaya 2008: 136–9). Critics have noted the tremendous transformation, not just in filmmaking techniques and aesthetics (Khoo and Barker 2010: 3), but also in the new involvement of women in the industry as directors, producers and other technical roles (Hughes-Freeland 2011; Sen 2005; Sulistyani 2009). So too the new era of democracy has encouraged some filmmakers to specifically confront topics which would not have been possible under the New Order, including political issues, the position of the Chinese in Indonesian society and youth disillusionment. There has also been a pronounced body of films which have engaged with issues of gay and lesbi sexuality, and to a lesser extent waria/transsexual subjectivities. Between 1998 and 2009 at least 35 films have portrayed non-normative sexualities and genders in one way or another.

It would be impossible to write about Indonesian cinema without referring to censorship, and while there is not space to discuss fully the various regulations that have operated during the period with which this research is concerned, it is crucial to note that at the time of the New Order, the censorship body was most concerned with any image or message judged to threaten the stability and security of the state. Censors were also concerned with issues of sex and to a lesser extent violence, and several of the films discussed in this book were censored.4 Sen has argued that almost every film produced in New Order Indonesia ‘has a narrative structure that moves from order through disorder to a restoration of order’ (1994: 159). This, she argues, results from the ‘particular history of this medium and the characteristics attributed to it by the New Order establishment’ (1994: 161). This narrative structure is very much evident in the New Order films discussed in this research. Cultural and political changes since 1998 mean that this structure is arguably somewhat looser in recent cinema, as are some censorship criteria. Nonetheless, displays of sex and intimacy continue to attract the concerns of censors, albeit erratically. These are issues which shall be returned to as the book progresses.

For those who are unfamiliar with Indonesia and its cinema, the number of films referencing gay, lesbi and waria subjectivities may prove surprising given its large Muslim population. However, it should be stressed at this point that there are no laws against same-sex acts between consenting adults in Indonesia, and while it is simplistic to characterize states and cultures as tolerant or otherwise, Indonesia is not a generally homophobic society. It is however, a country in which heterosexism is pervasive (Boellstorff 2007: 169), and the heteronormativity of the Indonesian government is overt (Davies 2010: 3). Incidents of violence and intimidation against waria, particularly those involved in sex work certainly occur, though doubtless many go unreported (e.g. Atmojo 1986: 11–13). Recent years have also seen a small number of events in which gay men as well as waria have been targeted and threatened (Boellstorff 2004b; Liang 2010; Oetomo 2001), in particular but not exclusively by the group known as Front Pembela Islam (FPI, Islamic Defenders Front). FPI threats and violence have been directed against events such as a regional meeting of the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA) in Surabaya and a 2010 workshop on transgender issues held in Depok, West Java (Liang 2010). The Q!Film Festival, established in 2002 and now held annually in Jakarta and a number of other cities has also been subject to intimidation and threats, most notably in 2010. In 2012 organizers decided to limit access to screening details by requiring those interested in the event to register online (Iwan 2012).5 Distressing as these events are, it should be recognized that the majority of community activities pass without problem. As Jamison Liang (2010) observed, ‘Islamist parties are chiefly concerned with countering events that aim to advance LGBT rights through education and awareness; they may be less interested in harassing a lone gay man, lesbian or waria on the street.’ It is difficult to explain exactly why certain events have been targeted, and to say if the events of 2010 mark a real trend. One question to ask is whether this violence is in any way a response to an increased visibility of sexual minorities in Indonesia, which is in turn reflected and further strengthened through popular media including cinema.

This project has proved to be somewhat larger than I envisaged when I first embarked on it. I did not wish to write something which took on the style of an encyclopedia or catalogue and for that reason I have chosen to focus on a select body of films which I feel to be of specific interest, perhaps as a result of the controversy they courted or because they illustrate a particular issue. Also, despite considerable efforts, I have not been able to access copies of all pertinent films, in particular some films from the 1970s and 1980s which, according to Kristanto’s 2007 Katalog Film Indonesia, contain storylines of relevance. Copies of those films may still exist somewhere, and it is to be hoped that they will receive the academic attention they deserve at some point in the future. Doubtless there are other films that I am not aware of. The earliest film discussed dates from 1973, and the latest film from 2009. More films of interest to this project have already been released since then and certainly others are in production or still in the minds of screenwriters and directors.

In this book I only discuss full-length fiction films that have been released in commercial cinemas. I exclude films made for television, short films or documentaries. Neither have I discussed what Gotot Prakosa has labelled side-stream films (2005: 3), which are those screened in film clubs, universities and film festivals. As Katinka van Heeren has stressed these side-stream films are a feature of both New Order and post-Suharto Indonesia. With the exponential rise in access to digital technologies, coupled with a relaxing of censorship laws, recent years have seen an explosion in side-stream films or what others have called film independen (van Heeren 2009b: 72–8). The distinction between mainstream and side-stream or independent film is somewhat fluid, and as John Lent has argued if one takes it to mean independence from mainstream studios, all Indonesian cinematic productions of recent years might now be described as independent (2012: 15). However, for my purpose here, it is useful to distinguish between those films which have passed through the state system of censorship and been screened in commercial cinemas and those Indonesian films which have only been shown in festivals and other non-commercial venues.6

Before introducing some of the key issues related to the representation of non-normative sexualities and genders in Indonesian media and specifically cinema, and the theoretical approaches which underpin this research, it will be useful to first contextualize the study by briefly surveying some of the key ethnographic work on gay, lesbi and waria Indonesians.

Genders and sexualities in Indonesia

In this book I define waria as male to female transvestites who are male bodied but generally describe themselves as having a female soul. As such, in their attraction to men, waria are expressing an attraction to the other rather than the same. A number of other terms for waria are used in Indonesian films, and these are noted in my discussions of specific movies. When talking about the subject position generally I use this current term which is preferred by waria themselves. Evidence for the existence of waria seems to date as far back as the early nineteenth century (Boellstorff 2004a: 163–4). Waria occupy diverse professions and come from a variety of religious, social and ethnic backgrounds. Nonetheless, they are perhaps most visible as a result of their tendency to work in hairdressing salons, and also by the fact that a number of waria engage in sex work. As Boellstorff states, ‘virtually everyone in Indonesia knows what “banci” or “bencong” (derogatory terms for waria) mean’ (2005: 57).

The term waria is a melding of two words: WAnita (woman) and pRIA (male). This was introduced in a 1978 decree by the Indonesian Minister of Religion, Alamsyah, apparently in response to concerns that the name of a prophet was associated with the previously used term wadam (Boellstorff 2007: 224). Wadam, explained variously as a joining of the words WAnita and aDam, or of the words haWA (Eve) and aDAM, had been introduced by the Jakarta Governor Ali Sadikin in the 1960s in order to endow the city’s transgender citizens with a certain degree of recognition and protection from the state (Atmojo 1986: 18). Prior to that a variety of terms had been used by and to describe waria, most obviously banci which continues to be used to this day, along with its slang variant of bencong. Because banci is often used pejoratively, waria themselves will generally prefer to be described as waria, though among themselves banci and bencong may still be used. It should also be noted that banci tends to have a wider meaning than waria. Dédé Oetomo lists an incredibly diverse set of examples of usage ranging from calling male fashion models banci-like, to parents calling their male children banci if they play with dolls (1996: 261). I have heard the term banci used pejoratively for gay...