![]()

Part I

Government Driving Innovation

![]()

1Who Drives Innovation?

John Rigby, Yanuar Nugroho, Kathryn Morrison and Ian Miles

Introduction

The development of new products, processes and services can be organized and led by many different actors in the economy and takes place at many different levels. After a strong government leadership of economic growth and development through extensive funding of technology programs during the 1960s and 1970s, the 1980s saw Western governments beginning to withdraw from the innovation process to a significant degree. During the 1990s, governments increasingly moved to assume enabling and regulatory roles, emphasizing freedom of choice for consumers in product and factor markets alike. Government has sought to facilitate innovation rather than leading it or driving it. But a number of recent policy initiatives arising within the EU suggest that there is now a wish to reverse this trend by making government once again a key actor in the innovation process, on the one hand through public procurement, and on the other hand, through giving government a key role in coordinating and leading so-called ‘social innovation’.

The new emphasis upon government as a central actor results from concern that within the EU economy, insufficient resources are allocated to R&D, compared with other major economic zones with which the EU is in competition, and that the current economic crisis may call for increased governmental spending on those areas that may command public support. Both key research and innovation Directorate Generals (DGs) (DG Research and Innovation and DG Enterprise and Industry) have been active in this area of policy. DG Enterprise has explored and continues to examine large-scale innovations that would have broad social impacts, following the example of programs that have been run at member state level. DG Research by contrast has begun to try to find ways of focusing the research systems of member states on large-scale scientific challenges that are defined at a European level. Reflecting the larger scale of these new kinds of initiatives in the context of science, DG Research has begun to use the term ‘grand challenges’.

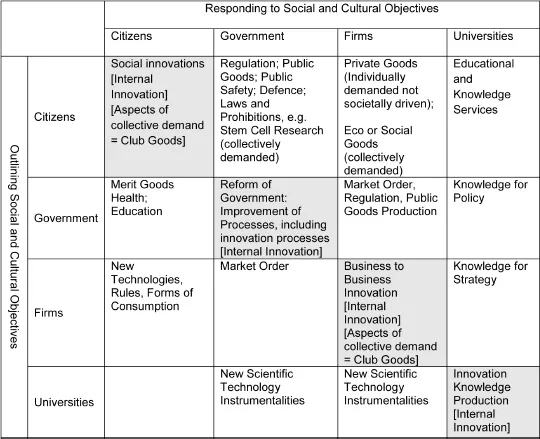

This chapter begins with typology that shows how different actors participate in the innovation process. The typology, which is shown in Figure 1.1, considers which factors determine where the leadership of innovation lies, and we then outline where government typically takes a key role in leading innovation. Our review of the policy literature suggests that the civil society/third sector is often vital, and government often builds upon the work of the third sector. The framework is then used to review and critically assess current EU policy for innovation.

Figure 1.1Actors of the innovation system and their respective roles.

Conceptual Review Outline of Innovation Systems Actors

Innovation processes vary from place to place and different authors emphasize different drivers and actors in their accounts. The broad trend in innovation studies has reflected increasing awareness, in both theory and policy, of the significance of interconnection between the actors involved in processes of innovation (e.g., Dosi, 1982). There has been a more inclusive view about who and what is involved in innovation, and to realize the importance of interaction between participants. This more inclusive perspective of the innovation and development has also extended to include efforts to grasp the complexity and iterative nature of these processes (e.g., Kline and Rosenberg, 1986). Those specialists focusing on innovation within the firm have also proposed more open models (cf. ‘open innovation’, Chesbrough, 2003). Major achievements of this debate have been the system of innovation approaches, advanced by Freeman (1998), Lundvall (1992) and Nelson (1993), which have formed the basis for policy-making at EU level and among a wide range of governments across the developed and less developed world. Within the EU, the so-called ‘Community Broad-Based Innovation Strategy’ is an example of such an approach.

Further developments include analyses of the relation between different key actors (Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff, 1998) of the nature of governance questions and the role of scientific knowledge (Gibbons et al., 1994; Nowotny et al., 2001). Attempts to promote engagement between actors include activities like foresight and technology assessment (TA)—particularly constructive technology assessment (CTA) (see Schot and Rip, 1997). Such attempts engage multiple actors to explore possible synergies and conflicts between future social and cultural objectives and opportunities for innovation provided by accumulating knowledge, especially scientific and technological knowledge. Principles emerging from this analysis have gradually informed innovation policy-making in a number of countries.

Analysis of the innovation process has generally focused upon the activity of major groups of actors—firms, government, universities/HEIs and laboratories—and the roles they take in delivering innovations. These groups interact, in various ways, to identify objectives and to produce innovations. But the form of interaction and the leadership can vary across cases. Citizens often appear in these analyses only as relatively passive and/or inhibiting actors, thus ‘public resistance to new technology’ is a common theme, along with calls for increased educational effort aimed at enhancing ‘public awareness/understanding’. But there are exceptions, in theory and practice, where a more sophisticated understanding of citizen roles exists. This is one of the central arguments in this chapter.

Indeed, different groups play different roles depending upon the nature of the need, and the type of innovation to satisfy it. Figure 1.1 provides a simple depiction of the relationships between the principal actors in the process of innovation. The figure shows the expression of need and does not explicitly consider resource flows, such as taxation. Expectations that are largely concerned with the innovation performance of the societal group are demands that are formulated within (and often met by) that group. Objectives can be formed individually or collectively. The figure identifies the conventional forms of economic production including private and public markets, but expresses other activities, including innovation by and within classes of actors. The expression of and provision of innovations often involves multiple sets of actors. It is not simply a link between two sets of actors.

The Role of Citizens

Citizens are capable of internal innovation. Their innovations often fall into the category of social innovations. Scholars often refer to social innovation by focusing upon the ways in which the collective processes involved in the definition of needs have been subject to change. This is reflected prominently and particularly in urban studies, policy studies and development studies, which have put more emphasis upon governance questions and the roles and social structures that underpin the definition of societal and individual needs (Moulaert et al., 2005; Swyngedouw, 2005; Davies, 2007; Taylor, 2007). Schumpeter (1980) also addresses innovation processes more directly with ‘creative destruction’ and defines entrepreneurs as people who combine existing elements in new ways. This idea informs subsequent studies on the importance of social factors affecting adoption and diffusion of technological innovations (e.g., Freeman, 1998). Citizens may organize themselves to articulate their social and cultural objectives, and seek new ways of meeting them. More technological innovation rarely involves more than incremental development, since the major technology advances are typically reliant on specialized knowledge and R&D. But there is much ‘user-driven’ input into establishing ways of using new technologies, and the malleability of information technology (IT), especially software, means that developments here are common.

Citizens demand external protection and other public goods from government. This may include regulation, which can be applied to any of the actors involved (including firms, universities and other citizens). There are often controversies in this area, with different groups having different views. Stem cell research is a good example of where different positions about ethical and moral dimensions exist. In the US, the Stem-Cell Research Enhancement Act of 2007, which seeks to increase the level of government funding for this form of research, has been opposed by many citizen groups and the presidential veto has been used to prevent the Act becoming law. (The Act was never in fact an act, but a bill, as it never became law.)

Citizens demand private goods and services from firms. This demand is expressed through market choice for those goods and services on offer. But both individually and collectively (e.g., in the form of voluntary organizations, civil society organizations and NGOs), citizens demand that firms provide private goods that may meet certain criteria, such as low environmental impact. These criteria may relate to broader public benefits or the requirements of specific consumers, or even run counter to wider considerations of the public good. Citizens also demand from universities educational and knowledge skills that allow them (or their children) to compete in the workplace or pursue other life goals. Citizens demand training, development, and education from the universities in a similar way to the way in which they demand goods and services from private firms. Information asymmetries are widespread in both instances, and provide a role for government. Generally, expectations on the part of citizens for education and research are not collectively defined. However, there may be times at which these become political issues. In the case of education, the questions of access and standards are often visible. In the case of research, the main concerns have predominantly centered on how it is conducted (e.g., use of animals, embryos) rather than on the goals, although goals can be morally, ethically and politically divisive.

The Role of Government

Government demand for public goods from firms should, in democratic societies, be derivative from the needs of citizens. The payment for the creation of such goods is from taxation. Government creates merit goods, the consumption of which is seen to be in the interests of citizens (reflecting how social needs have been defined). Some of these are produced directly by state-run public services, some are produced by the private sector, but the market is largely one with government purchasing providing the income stream to firms. The production and consumption of such goods are classically said to be driven partly by enlightened citizens and partly by government, which must provide extra supply of some goods and services where some citizens fail to recognize the benefits of making their own market choices to invest in them (e.g., health insurance in many countries). Political economists recognize that government actions often reflect the articulation of interests by organized groups (e.g., politically strategic economic groups (like small farmers), firms regarded as ‘national champions’ and scientific and professional elites).

Government also innovates internally. Much of its innovation is aimed at achieving greater efficiency in the provision of public goods. A great deal of current activity surrounds e-government, which many commentators see as potentially transforming relationships between the state and its citizens. Government may also have the expectation that firms will be productive and efficient and, by achieving this, will have more resources with which to support its activities, as well as operating in an economic environment that is likely to be more affluent and less prone to problems such as high unemployment. Government seeks information and advice about policy from knowledge-producing activities, and the demand for innovation policy is central to its regulatory role. In formulating innovation policy it will necessarily be required to take into account the expressed (and imputed) needs of other actor groups.

The Role of the Business Sector

Firms seek to promote their innovations to citizens, who will buy them as private goods. The expression of needs through the market is often the result of extensive prior interaction. The market economy provides a set of mechanisms that allocate resources to the satisfaction of private needs. Firms, often acting with other knowledge producers such as universities, define the forms that such products and services take. Firms seek a legal and regulatory system to allow markets to operate effectively. Steps to protect innovation—for example, by intellectual property (IP) regulation— may be urged by firms. Within the context of such private good production, there can be some aspects of the product or service and/or the production process that are regulated. An example might be safety and environmental performance. This form of regulation is society-driven, even when there is no explicit innovation agenda involved. Firms are regulated for the benefit of society through the political process, and regulations may or may not impact innovation processes and trajectories. For instance, regulations about health and safety at work may lead to innovations that increase automation at the workplace, even if this is not the intended impact. In contrast, regulations aimed at reducing use of an environmentally damaging process may simply result in a firm relocating its activities overseas, without damage being mitigated. Firms may also innovate themselves and within/across business sectors. Such innovation may be termed ‘internal’.

There is the argument in some schools of thought, however, that regulation-driven innovation might be considered counter to society-driven innovation and that regulation might actually impede the ability to innovate, limit knowledge sharing, particularly through intellectual property rights (IPR), and furthermore, in some cases, prevent societal needs from being met, especially in less developed countries. Some have advocated a ‘prize’ system instead of IPR to overcome this (see, for example, Stiglitz, 2006). This approach has been practiced with success in California, and in 1999 Sweden launched its own ‘Environmental Innovation Competition’ for innovations that are ‘customer oriented’ and have a ‘clear environmental objective’ (TrendChart website1). This type of approach, however, only really works when there is a clear objective and a clear need to be met.

The Role of Universities

Universities, like businesses, face regulation of their activities by government. This arises from the need to provide a measure of standardization for prospective students to be assured of the quality of education available, as well as reflecting policy objectives such as increasing workforce skills and attainment levels and creating a strong science base. Universities demand scientific equipment and techniques from firms, ‘instrumentalities’,...