![]()

1

The Fundamentals of Electricity

- Electric Charge

- Electric Current

- Energy

- Electric Potential

- Electric Potential Difference or Voltage

- Voltage Measurements

- Electric Power

Introduction

It is easy to see or hear the effects of electrical devices. Hearing aids amplify sound, lightbulbs light, and cellular telephones connect you to the world with pictures and sounds. However, the inner workings of electrical circuits cannot be directly observed. Specialized instruments must be used to detect and measure electrical quantities within circuits. The discussion of these electrical quantities at first may seem somewhat abstract since you cannot see or hear them. However, in time, as your experience with electrical instruments grows, you will become comfortable with identifying, measuring, and manipulating electrical quantities within circuits.

If you are intimidated by electricity because of fear of electric shock, rest assured that most of the circuits you will encounter in your studies of electronics pose no danger of shock. When the time comes, your instructor will ensure that you are adequately trained and prepared to handle circuits that could shock you. You will learn appropriate safety precautions to protect yourself and your patients from electric shock as you perform electrical measurements on their bodies in procedures such as electronystagmograms and auditory-evoked potentials.

The Concept of Charge

When Jimmy was 10 years old, he discovered a marvelous way to torment his younger sister. On a dry day, he would drag his feet across the living room carpet, then sneak up behind Cathy and touch her ear. The electricity passing between his finger and her ear brought squeals of shock and looks of outrage that he found delightful.

Electrified bodies are part of our everyday experience. Certainly, Jimmy was electrified after rubbing his feet on the carpet. Actually, the carpet also was, although that was not as obvious. You could say that electrified bodies possess electric charge, or equivalently, they are electrically charged. This effect can often be produced simply by rubbing two things together. Common laboratory demonstrations involve rubbing a plastic rod with rabbit fur or a glass rod with a patch of silk. You can electrify a nylon comb simply by combing dry hair. Clothing becomes electrified when it tumbles in an automatic dryer.

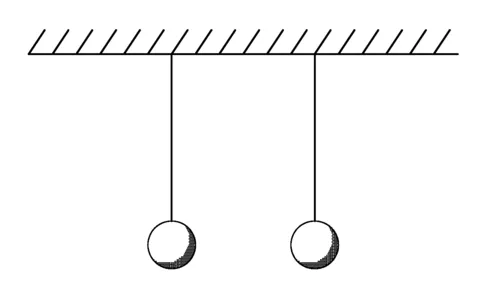

Electrified bodies exert forces (pushes or pulls) on each other. For example, clothes pulled from an automatic dryer sometimes stick to each other or to the dryer, and other times they repel each other. However, sometimes the pushes and pulls can be a rather subtle effect. After rubbing his feet on the carpet, Jimmy certainly did not notice any new force acting on his electrified body, but he did experience a wonderful sense of power in his ability to shock his sister. To study the forces exerted on charged bodies, you need something really lightweight, like balloons or little Styrofoam balls suspended from threads, as in Figure 1.1. Styrofoam balls can be electrified by touching them with almost anything that has been charged or by rubbing them with wool. Such experiments reveal that, when electrified, the balls sometimes attract each

Figure 1.1 Uncharged balls hang from strings.

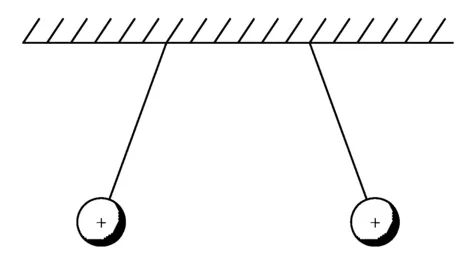

Figure 1.2 Like charged balls repel each other.

other, and sometimes they repel. It seems to depend on which types of materials are rubbed together to produce the electrification.

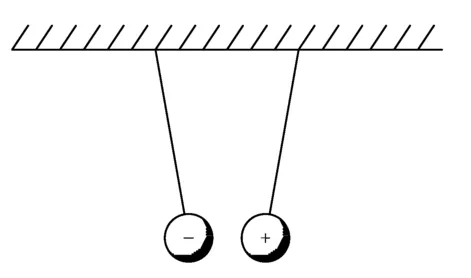

Benjamin Franklin was the first to clearly explain these effects. He and his contemporaries recognized that there are two kinds of electric charge. Franklin labeled them positive and negative. He could have called them red and green or up and down, but he did not. Franklin’s genius lay in recognizing from his experiments that equal amounts of unlike charges can neutralize each other, just as the sum of equal positive and negative numbers add up to zero (Neuenschwander, 2006). When two bodies are electrified with the same type of charge, they are repelled from each other, and when they are electrified with opposite types of charge, they attract, as shown in Figures 1.2 and 1.3, respectively.

Franklin and others observed that different materials accumulate different charges. By Franklin’s specific definitions of positive and negative charge, a glass rod rubbed with a piece of silk becomes positively charged, and the silk becomes negative. A plastic rod, on the other hand, becomes negatively charged when rubbed with fur, while the fur becomes positive. The charges can be examined by touching the rods to

Figure 1.3 Unlike charged balls attract each other.

hanging Styrofoam balls and observing the attraction or repulsion of the balls depending on the charges.

You may be wondering, “Where does this charge come from?” Scientists now know that most of the matter you encounter every day contains equal large quantities of positive and negative charge. Each atom of matter has equal numbers of positive protons and negative electrons. A body becomes electrified when there is a charge imbalance. Too much positive charge (more protons than electrons) makes the body positive; excess negative charge (more electrons than protons) makes it negative.

In conclusion, bodies can be electrified with either of two types of charge, positive or negative. Two bodies that are electrified with the same type of charge repel each other, while two bodies electrified with opposite types of charge attract each other.

Quantities of Charge

Charge is a measurable quantity. Charles Coulomb, a French contemporary of Benjamin Franklin, invented a type of sensitive balance with which he was able to carefully measure the force between two electrified bodies and thus their charges. He found that the force is directly proportional to the amount of charge on either body, and that it gets stronger as the bodies are moved closer together. In honor of Coulomb’s work, a unit of charge is called a coulomb, spelled with a small c so the unit is not confused with the man’s name, and the unit coulomb is abbreviated with the letter C, capitalized.

It turns out that a coulomb of charge is quite large. In your applications of electronics, you will probably never encounter an isolated charge so huge. You will more likely use un...