![]() Part I: Structure

Part I: Structure![]()

Chapter 1

Productive Enterprises

Categories of Enterprises

Before describing the governmental organs which plan and control the economy, it is desirable to start at the bottom and consider the organization and finance of enterprises and individuals actually engaged in the production of goods and services. These may be conveniently divided into the following categories:

- State enterprises.

- Non-agricultural co-operative enterprises.

- Collective-farms (Kolkhozy).

- The private sector, subdivided into

- Agricultural holdings of collective farmers and state employees.

- Private craftsmen, individual peasants, professional services.

Before describing each of these forms, it is necessary to mention the types of economic activity, familiar in the west, which are not to be found in the USSR, or are illegal there. The laws and regulations have changed very little in these respects since the liquidation of NEP1 at the end of the 'twenties.

It is illegal for any private citizen to employ anyone to produce a commodity for sale. For example, a private shoemaker, whose existence is legitimate under category (d)(ii) above, may not employ an assistant. It is legal to employ a domestic servant, who 'produces' nothing in the Soviet sense of the word, and no doubt many writers employ a typist privately, but in principle the 'exploitation of man by man' is repressed by law. It is also illegal for an individual to sell anything he has not himself produced (unless, of course, he is an employee or member of an organization which has the right to produce goods for sale). For instance, a peasant can sell a cabbage he has grown, any citizen can make coat-hangers in his spare time and sell them in the free market. But if a man buys on his own account a sack of cabbages from peasants and then resells them at a profit in a city where cabbages are dear, or if he buys a scarce commodity in a state store and resells it at a higher price, he is guilty of a criminal offence and, if caught, would probably serve a term of imprisonment. Of course, this does not mean that such activities do not exist. On the contrary, it may readily be observed that ticket touts outside a Soviet football stadium or the Bolshoi theatre are as active as their equivalents in London or New York, and there can hardly be a peasant in all Russia who has not committed the technical 'crime' of selling in the free market not only his own produce but that of some fellow-villager. However, none can doubt that the legal principles mentioned above deeply influence economic organization.

Since even within the sectors in which private or co-operative activities are nominally permitted, the state organs have and frequently use the right to refuse the necessary registration permits, it follows that a wide range of goods and services are either provided by state organs or are not provided at all. To take two small instances, it would not be open to an individual to open an agency to provide addresses for holiday accommodation, or a cafe, and if the appropriate state organs do not feel that it is necessary or desirable to provide them, then they cannot be brought into existence.

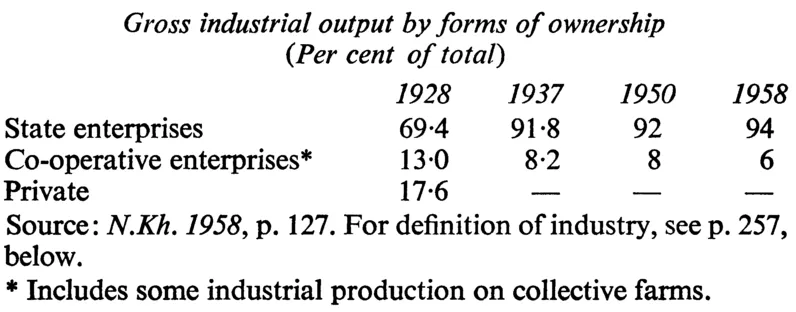

The relative importance of the various categories can be expressed in a number of different ways, according to the sector of the economy and the basis of the comparison. Thus, taking gross industrial production as a measure, the figures are as follows:

Building is not included in the above table. The relative importance of the non-state sector there is much larger than in 'industry'. Collective farms erect various farm buildings and other constructions, while private persons built houses in substantial numbers throughout the Soviet period. Thus in 1958, out of a total new housing space of 71-2 million square metres (exclusive of peasant construction), 24-5 million were privately built; in addition, peasants and 'rural intelligentsia' put up about 700,000 dwellings.1

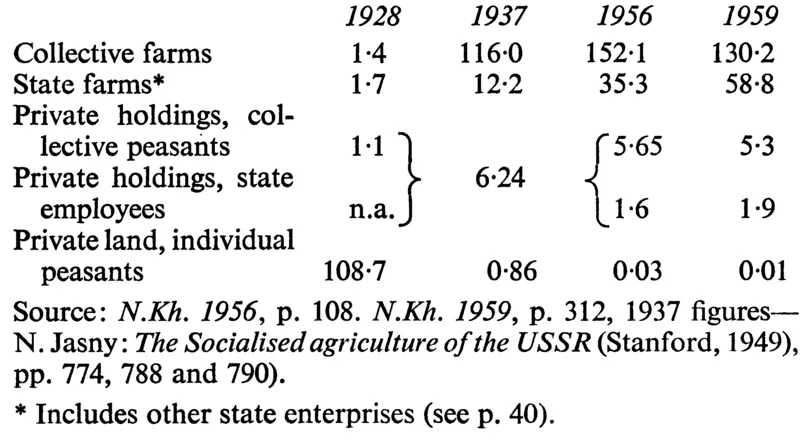

Total agricultural output is not subdivided, in published statistics, by forms of ownership, but the following are the relevant figures in respect of land area. These strikingly demonstrate the effect of collectivization, and also of the growing importance of state farms.

Sown area (millions of hectares)

(Soviet territory as of the given date)

However, a high proportion of livestock was, and is, privately owned; though this proportion has been falling, even as recently as January, 1959, over half of all cows were private, and this sector also produced over half of the meat and potatoes and nearly all the eggs of the Soviet Union. An American calculation, based on a mixture of official statistics and estimates, gives the total output of the private sectors as about 30 per cent of all agricultural production for the year 1956.2 This is likely to be close to the mark.

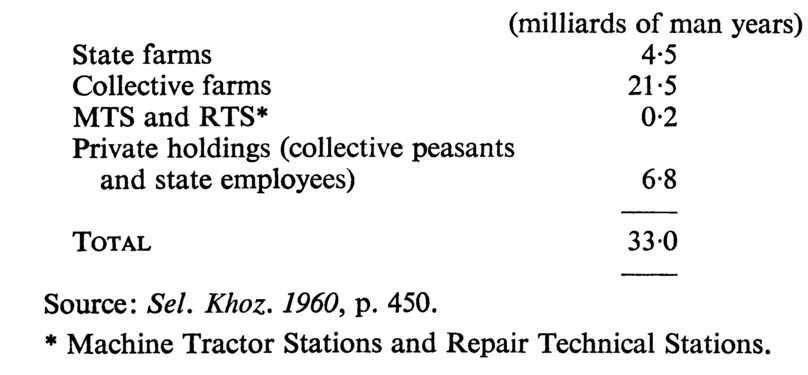

The relative figures for labour were given as follows for 1959:

State and 'co-operative trade—the latter to all intents and purposes being a branch of state trade (see page 41, below)—was responsible for over 94 per cent of all retail trade in 1957 and 1958, the remainder being accounted for by the free market. However, the free-market data include only urban sales, intra-village trade being omitted. The statistics also omit many unrecorded transactions between individuals.

Transport is run by state enterprises, with the significant exception of collective-farm haulage. There are a few privately owned horses, and some private cars run an illegal taxi service.

For other economic sectors, mostly services, no statistics are available for the relative importance of different types of enterprise.

The State Industrial Enterprise

A state enterprise belongs to the state. From this apparently tautological statement of the obvious flow a number of consequences which are perhaps less obvious. In essence and in law, the enterprise is a convenient unit for the administration of state property. It is a juridical person, it can sue and be sued, but it owns none of its assets. The director and his senior colleagues—the chief engineer, who acts as his deputy, and the chief accountant—are appointed by state organs to manage the state's assets for purposes determined by the state. This is why there is no charge made for the use of the enterprise's capital, since it belongs to the state anyhow. This is also why the state is entitled to transfer the enterprise's profits to the state budget, save for that portion which the state's regulations or ad hoc decisions permit the enterprise to retain. That is why it is within the power of state organs to take away any of the enterprise's assets, if they think fit, without financial compensation.

The director is in sole charge, in the sense that he is responsible to those who appoint him and must be obeyed by his subordinates. However, this principle of 'one-man command' is subject in practice to a number of significant limitations. Not only are the director's hierarchical superiors liable to issue detailed orders on almost every conceivable subject, but he must also take into account a number of inspecting and checking agencies. The most important of these, which also exercises a controlling influence over other agencies, is the Communist party; this generally possesses an organized group within the enterprise, of which the director is usually a member but in which he holds no official position. There is also a trade union branch, to which certain questions (such as distribution of premia, overtime work, norm-setting, questions of labour discipline) must be referred. Since 1958, there is also an elected 'permanent production council', which, though without direct executive authority, is entitled to deliberate on many questions directly affecting planning and management. There are also outside agencies of inspection and control: the banks, financial inspectorates and some others; these will be examined in due course (see pages 92 and 111). The successful director requires to possess qualities of diplomacy, to obtain the support or avoid the opposition of these various controlling, checking and inspecting agencies. None the less, he is in command; he is to blame when things go wrong and is rewarded when they go right.

The primary task of the director is to fulfil, and if possible to overfulfil, the output plans, and to utilize the resources placed at his disposal with due regard to economy. The output plan specifies the quantity of the product required in the given month, quarter or year, with some details of type, design, assortment, etc., where this is relevant. The aggregate output plan of industrial enterprises is frequently expressed in physical measure (tons, square metres, etc.), or, where this cannot be done, in terms of value (roubles of gross output). There are usually a number of other plan 'indicators': cost reductions, increase in labour productivity, economy of scarce materials and sometimes other indicators appropriate to the given sector or the result of some campaign of the moment. Fulfilment of plans expressed in terms of these various indicators carries with it moral approbation and material benefits, in the form of substantial premia to the director and his senior staff, and so they could be conveniently designated 'success indicators'. Overfulfilment carries with it increased rewards, material and spiritual. Thus in the oil industry in 1956 the director received a bonus of 40 per cent of his salary for fulfilling the output plan, and 4 per cent for each 1 per cent overfulfilment. Those who overfulfil, or fulfil ahead of time, receive praise, sometimes see their picture in the newspapers and may receive decorations. Of course, not all of these plans are equally important, either from the standpoint of premia or in the weight given them by superior authority in assessing the success of the enterprise, and, since it often happens that directors are unable to fulfil all the various plans, they naturally choose the ones that seem to them the most important. This has generally been the production plan in quantitative terms, reflecting the great emphasis on growth, though recently it is being modified by insistence on cost reductions. The consequences of the 'success indicator' system will be discussed at length in chapter 6.

Soviet enterprises, with very few exceptions, now operate as autonomous financial entities with their own profit and loss accounts, a status known by the Russian words khozyaistvennyi raschyot ('economic accounting'), usually abbreviated to khozraschyot. It was not always thus. In the period of 'war communism', that is, before 1921, most state enterprises had no funds of their own, wages and other expenses being met out of the state budget. In the years of NEP, before 1929, all except very large state enterprises were still 'not on khozraschyot', in the sense that their revenues were paid into, and their expenses were met out of, the accounts of trusts, which grouped together varying numbers of enterprises. It was only in 1929 that a decision was taken to place state enterprises on khozraschyot, and since this date there have been few exceptions to this rule. The basis of khozraschyot has been defined as follows: 'A method of planned operation of socialist enterprises .. . which requires the carrying out of state-determined tasks with the maximum economy of resources, the covering of money expenditures of enterprises by their own money revenues, the ensuring of profitability of enterprises'.1 So far as the enterprise is concerned, prices of outputs are fixed, prices of inputs are fixed, and, as we shall see, the choice as to which inputs to use is severely limited by the system of allocation. Within these bounds, it is the director's job not only to fulfil the various plans already referred to, but also to cover his costs and to make a profit. This is encouraged by providing an incentive linked with profits. The incentive is related not so much to profits as such as to overplan profits, since it is considered that some enterprises earn profits because of 'unearned' advantages of location or equipment, and such advantages find expression in the planned profits; only a very small proportion of planned profits may be retained, whereas enterprises are encouraged to make overplan profits, that is, to make special efforts to economize. The incentive to maximize profits takes the form of the so-called enterprise fund, known until 1955 as the director's fund, which the enterprise retains and uses mainly for purposes which benefit its personnel; these include the financing of investments in addition to plan, primarily in housing and amenities, and also in bonuses to outstanding workers. The trade union branch must be consulted.

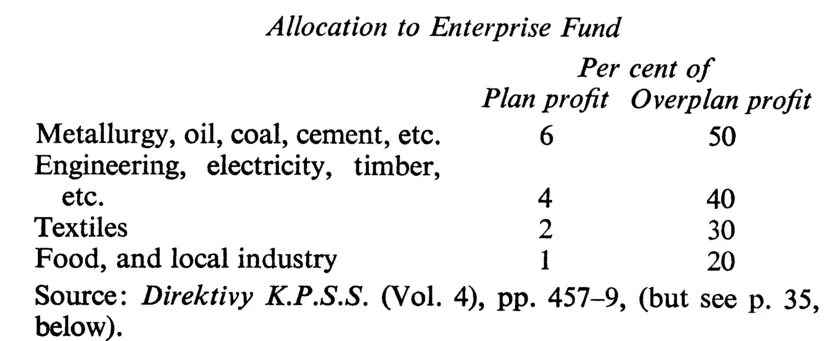

The rules governing the enterprise fund have often been changed. From 1956 it is based on the following percentages, subject to the total not exceeding 5 per cent of the wages bill:

In addition, under a decree issued in 1957, up to another 30 per cent of overplan profits can be devoted to housing.1

By decree published on July 2, I960, exceptional treatment is accorded to 'machine-building and metal-working'. Enterprises in this sector are entitled to retain 10 per cent of those planned profits which arise from the production...