![]()

Positive Practice as a Developmental and Recursive Process

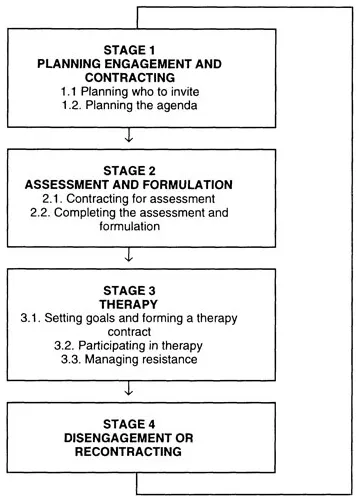

Positive Practice may be viewed as both a developmental and a recursive process. It is a developmental process insofar as it consists of a series of distinct stages. At each stage key tasks must be completed before progression to the next stage. Failure to complete the tasks of a given stage before progressing to the next stage may jeopardise the consultation process. It is a recursive process insofar as it is possible to move from the final stage of one episode of consultation to the first stage of the next. The process is diagrammed in Figure 1.1. What follows is a description of the stages of consultation and the tasks entailed by each.

Figure 1.1. Stages of the consultation process

Stage 1. Planning Engagement

There are two main things that the therapist has to plan before the first session: (1) who to invite to this meeting and (2) what to talk to them about.

Stage 1.1. Planning who to invite

To make a plan about who to invite to the first session, the therapist must find out from the referral letter or through telephone contact who is involved with the problem and tentatively establish what roles they play with respect to it. With some cases this will be straightforward. But in others, it will be complex. In one instance, I was referred a family where over fifteen professionals were involved along with four foster parents. Positive Practice provides a system for mapping out the roles that each member of the problem system play. This is described in Chapter 2. Once each person’s role has been established, decisions about who to invite to the intake session may be made. One particularly important role in the problem system is that of the customer. Customers are those members of the system most eager to see the problem resolved. Customers are always invited to the first session. The decision about who else to invite will depend upon the roles they are suspected to play in the problem system and their availability.

Stage 1.2. Planning an agenda

In Positive Practice the therapist explicitly forms a preliminary formulation on the basis of the information in the referral letter or the referral telephone contact. This preliminary formulation or hypothesis is constructed according to a specific model. This three column formulation model, which is elaborated in Chapter 3, takes account of the current pattern of interaction around the presenting problem, the beliefs and other cognitive factors that constrain system members from breaking out of this problem-maintaining cycle of interaction, and historical events or other factors which underpin these constraining beliefs. The preliminary formulation or hypothesis provides the therapist with a number of avenues of questioning to pursue in the first interview when inquiring about the presenting problem, its evolution, maintenance and exceptional circumstances where the problem does not occur. The preliminary formulation also suggests areas where detailed inquiry is worthwhile when taking developmental and family histories and constructing a genogram.

Stage 2. Assessment and Formulation

Establishing a contract for assessment, working through the assessment agenda, developing a formulation on which to base treatment and trouble-shooting difficulties associated with non-attendance are the more important features of the assessment and formulation stage.

Stage 2.1. Establishing an assessment contract

At the outset of the assessment session the first task is to explain what assessment involves and to offer each member of the network a chance to accept or reject the opportunity to complete the assessment. For most parents, this will involve outlining the way in which the interviews will be conducted. The concept of a family interview with adjunctive individual interviews is unusual for many parents. Most parents need to be told about the time commitment required. An assessment may require between one and three sessions. It is important to highlight the voluntary nature of the assessment. It is also important to clarify the limits of confidentiality. Normally, the contents of sessions are confidential unless there is evidence that a family member is a serious threat to themselves or to others.

With children and teenagers, misconceptions need to be dispelled. For example, some children think that they will be admitted to hospital and others believe that they will be put in a detention centre. In some instances children may not wish to attend but their parents may be insistent. In others, parent’s may not wish to attend but a referring physician or social worker may forcefully recommend attendance. In such situations, the therapist may facilitate the negotiation of some compromise between parties. For example, an agreement may be reached that a child will attend but not participate in the interview until the last fifteen minutes. If a cotherapy team is conducting the interview or a team and screen are in use, the roles of team members and the way in which the screen works needs to be explained. If sessions are to be videotaped, legally responsible guardians of children must sign the consent forms which stipulate the limits of use of these tapes. The contracting for assessment is complete when family members have been adequately informed about the process and have agreed to complete the assessment. Chapter 4 contains a detailed guide to the development of an assessment contract and also highlights ways of dealing with contracting problems.

Stage 2.2. Completing assessment and formulation

An assessment typically involves between one and three family interviews. These focus on working through the planned agenda developed in Stage 1.2 so that the therapist and the family may construct a three column formulation of the problem. The assessment is complete when the presenting problem and related difficulties are clarified, the cycles of social interaction within which these problems are embedded have been described, the factors that prevent involved members of the problem-system from breaking out of these cycles of interaction have been agreed upon, and exceptional circumstances where the problem does not occur have been identified. Exploring the child and family histories and constructing a genogram are typically employed as ways of bringing forth information useful for constructing the formulation. A detailed account of assessment procedures is presented in Chapters 5 and 6. The process of assessment also serves as a way for the family and therapist to form a working relationship, a relationship that will be vital for the success of therapy if the family opt for this.

Difficulties in engaging family members in the assessment process sometime occur and many of these are discussed in Chapter 2. Positive Practice offers ways for trouble shooting these difficulties. In some instances, the preliminary mapping of the problem-system may be at fault and, for example, the customer may have been misidentified. In other cases customers may require coaching on how to engage other family members in therapy.

Stage 3. Therapy

Once a formulation has been constructed the family may be invited to agree a contract for therapy, or it may be clear that therapy is unnecessary. In some cases, the process of assessment and formulation leads to problem resolution. Two patterns of assessment-based problem resolution are common. In the first, the problem is reframed so that the family no longer see it as a problem. For example, the problem is redefined as a normal reaction, a developmental phase or an unfortunate but transient incident. In the second, the process of assessment releases family members’ natural problem-solving skills and they resolve the problem themselves. For example, many parents, once they discuss their anxiety about handling their child in a productive way during a family assessment interview, feel released to do so.

In other cases assessment leads on to contracting for an episode of therapy. Therapy rarely runs a smooth and predictable course, and the management of the difficulties and impasses that develop in the midphase of therapy is an important aspect of Positive Practice.

Stage 3.1. Setting goals and forming a therapy contract

The contracting process involves presenting a clear formulation of the problem, establishing clearly defined and realistic goals and outlining a plan to work towards those goals. Ways of managing this process are discussed in Chapter 7. Of all of these tasks, goal-setting is the most vital. Clear, realistic, visualised goals that are fully accepted by all family members are crucial for effective therapy. Chapter 8 addresses the issue of goal-setting. The contracting session is complete when all involved members of the problem-system necessary for implementing the plans agree to be involved in an episode of therapy. Therapeutic episodes are time limited. Common time frames are three, six or ten hourly sessions spaced at increasingly expanded intervals from between a week and three months.

The major stumbling block here is to identify goals that all members of the family can agree upon. Goals are discussed in Chapter 8.

Stage 3.2. Participating in therapy

Therapy in Positive Practice involves two main processes: focusing on behaviour and focusing on beliefs. In the first the therapist and the family work directly on breaking the cycle of interaction around the presenting problem. This often involves the family completing tasks within the session, or as homework between sessions, and reviewing the effects of these tasks on the problem. This aspect of Positive Practice, which is covered in Chapters 9 and 10, draws heavily, although not exclusively, on the structural (Colapinto, 1991), strategic (Madanes, 1991), problem-focused (Segal, 1991), solution-focused (deShazer, 1988) and behavioural traditions (Falloon, 1991) within the family therapy field.

In the second major therapeutic process, the therapist and the family aim directly to transform the belief system that underpins the pattern of interaction in which the presenting problem is embedded. If the belief system is transformed, then the pattern of interaction will change and the problem will resolve. The transformation of belief systems in Positive Practice involves the use of a variety of interviewing techniques which have evolved from the Milan Systemic Family Therapy (Campbell, Draper and Crutchley, 1991) and the emerging Post-modern tradition within the field (Gilligan and Price, 1993). These are described in parts of Chapter 10 and Chapter 11.

While much therapeutic communication within Positive Practice takes place within family therapy sessions, this is not exclusively the case. In certain circumstances therapy may occur through letter writing, individual sessions with children and network meetings involving professionals from agencies that have significant contact with the family. Letters, child-centred sessions and network meetings are discussed in Chapters 12, 14 and 15.

Stage 3.3 Troubleshooting resistance

Between contracting for therapy and agreeing to terminate the therapeutic process, many hitches will occur in most cases. For example, family members may miss appointments, not complete homework assignments, participate in therapy sessions in ways that prevent progress or revert to an individualistic formulation of the problem. On some occasions this resistance will present as a therapeutic crisis. Often therapists and other professionals in the problem-system develop countertransference reactions, in response to resistance or crises, which lead them to replicate dysfunctional patterns of interaction that occur in the families with which they work. In Positive Practice, the therapist is prepared for these and other forms of resistance and troubleshoots each resistance in a systematic way. The resistance must be described clearly, possible factors contributing to it mapped out and options for overcoming it explored. Resistance, therapeutic dilemmas, crises and countertransference are dealt with in Chapters 11 and 13.

Stage 4. Disengaging or recontracting

An episode of therapy is completed when the therapeutic plan has been implemented in its original or modified form, where whatever resistances to implementation have been dealt with, where relapse management has been discussed, and where goal attainment has been assessed.

Where therapy has been unsuccessful, as it will be in about 25% of cases (Carr, 1991a), it is vital to explore the reasons for failure with the members of the problem-system In some instances it may be that the approach to consultation described here is an inappropriate way to re...