eBook - ePub

The Concise Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Volume 2

- 650 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Concise Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Volume 2

About this book

The Concise Garland Encyclopedia of World Music comprises two volumes, and can only be purchased as the two-volume set.

To purchase the set please go to:

http://www.routledge.com/9780415972932

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Concise Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Volume 2 by Garland Encyclopedia of World Music in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

8. East Asia

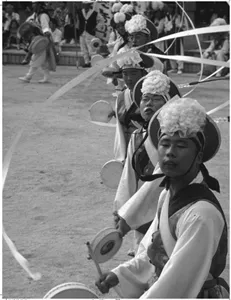

Sogo players in nongak incise patterns in the air with ribbons attached to their hats, Seoul Nori-Madang, South Korea, 1990.

Photo by Keith Howard.

Photo by Keith Howard.

8. East Asia

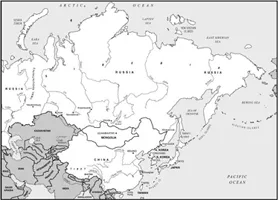

This section on East Asia covers China, Japan, Korea, and part of Inner Asia—Mongolia and Tuva. The region is vast in terms of time and space: the chronology in figure 1 shows that time in this context can be measured not merely in centuries but in millennia. The music that has developed in such an immense area over such a long span of time is widely diverse, as, of course, are the people who have created it. Music makers in East Asia include emperors, beggars, scholars, farmers, warriors, concubines, wandering monks, fishermen, shamans, actors and actresses, revolutionaries, civil servants, herders, priests, and rock stars. Their musical instruments include those fashioned from bone and stone in prehistory and those devised by sophisticated avant-garde composers of our own time, seeking new sounds and new effects. Contexts of musical creativity and performance include palaces, teahouses, fields and waterways, city streets, private homes, theaters, concert halls, and stadiums.

The articles that follow, though they can only begin to suggest the depth and breadth of this subject, will be a useful starting place for the reader. The introductory article that follows profiles the region and its musics.

East Asia

A Profile of East Asian Musics and Culturess

Although some scholars have described East Asian societies and their musics in terms of a polarity between “great” traditions (centralized, urban, official, orthodox) and “little” traditions (regionally varied, rural, unofficial, heterodox), there is actually a continuum rather than a sharp division between the national and the regional, and interchange between centers and peripheries has shaped much of the history of East Asian music. Musical regions have developed in conjunction with linguistic dialects.

Classical, Folk, and Popular Music

While most English-speakers have a sense of distinction among the terms classical, folk, and popular music, their exact definitions and lines of demarcation are somewhat ambiguous, and in East Asia the situation is even more complex. In East Asia, although some classical music (as in the West) is old, precisely written down, and performed by professional specialists, the tradition of the scholar-amateur who performs for self-cultivation is also widespread, and new dynasties often developed their own new or reconstructed “classical” music to supersede that of the outgoing regime. In modern times, the term “popular music” is associated with the mass media, but for centuries before the advent of radio, television, films, and recordings, a variety of singers, storytellers, and actors provided popular entertainment for the masses. Music in the courts and among the literati has constantly borrowed from folk and popular traditions; in a similar manner, many modern concertized traditions are based on music (and dance) orginally performed as entertainment in villages or teahouses, or in ritual contexts such as weddings, funerals, and religious or shamanistic ceremonies.

Sound and Ideas

In many types of East Asian instrumental and vocal music, a great deal of attention is lavished on the production of individual sounds: a single “note” may have subtle and complex changes in pitch, timbre, and volume. Musicians and scholars have developed a large vocabulary for these nuances, which are only hinted at in English terms like ornament or vibrato. However, many musical phenomena and techniques

Note on Transliteration

This section uses pinyin romanization for the Chinese,the Nippon system for Japanese (including its slightly modified version, the kunrei ‘official order’ from the government system), and the McCune-Reischauer system for Korean. Naxi-language terms are Romanized in standard Naxi pinyin. Mongolian transliteration follows local practice. With the exception of important words that have moved from Oirat to Khalkha Mongolian, romanization of the official Cyrillic orthography is used for Mongolia, and of the Mongolian classical script for Inner Mongolia.

Throughout the volume, exceptions to these guidelines are made for certain proper names and other terms that have become widely known in another spelling, and when contributing authors prefer a different spelling for their names. For internationally known performers, composers, and scholars, their own chosen spellings are used; in some cases standard romanized spellings are also provided.

are so obvious to musicians that they have no special name: for example, the standard downward plucking stroke for the Japanese syamisen ‘samisen’ or the divergence among melodic lines in Chinese ensemble music that Western scholars call “heterophony.”

Natural sounds such as audible breath in playing a bamboo flute or fingers sliding along strings are often integral to East Asian music. A close connection with nature is also exemplified by the idea of program music: an instrumental piece may refer to a historical event or legend, a poem or novel, a scenic locale, a season, a bird, or a flower. Particularly in musical theater, sounds may clearly represent things that are not seen onstage, some as obvious as a rooster’s crow or horses’ hooves, others understood only by those familiar with the conventions of a particular genre.

The organization of music varies enormously, but in many parts of East Asia, long multisection musical forms have developed. These may be instrumental (Korean sanjo or Yongsan hoesang, Chinese xianshiyue and Jiangnan sizhu), vocal (Chinese nanquan), a combination of instrumental and vocal sections (Japanese nagauta and sankyoku), or a mixture of singing and heightened speech (Chinese opera; Korean p’ansori).

Oral and Written Traditions

Although some of the oldest surviving examples of musical notation in the world can be found in China,

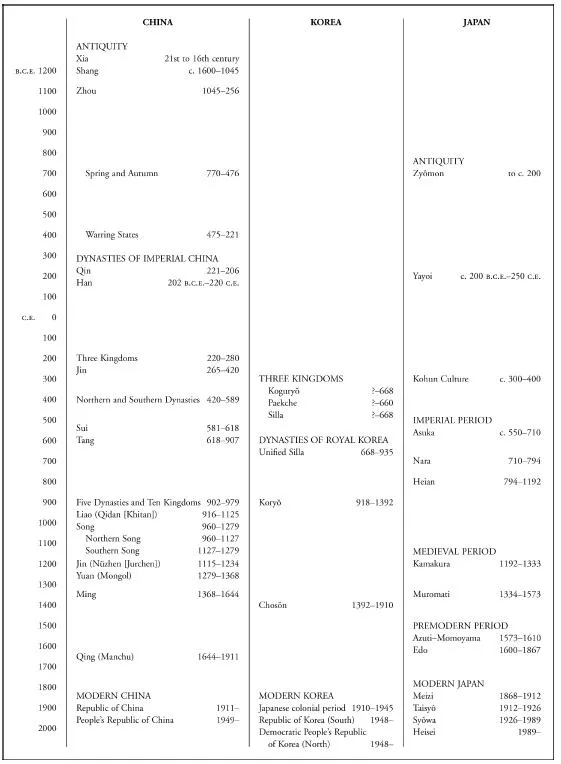

Figure 1 Chronology of East Asian history

Japan, and Korea, the nature and purpose of written music in these civilizations have often been rather different from those of their Western counterparts. In many cases, melodies are given in skeletal form, with details of ornamentation and technique to be learned aurally, realized in performance, or both. In other cases (most famously in the music for the qinzither of China), finger techniques are written with great precision, while rhythms are a function of the player’s memory or imagination. Even in the most refined or carefully notated traditions, aural learning has had a central role, and a wide variety of mnemonic systems have evolved. Although these systems are sometimes written down, they function primarily as a tool for oral teaching, learning, and remembering, with syllables representing everything from court melodies to strokes and combinations for percussion instruments. Improvisation often has a role at a relatively “micro” level, with basic melodies and structures fixed while considerable freedom is allowed in the individual player’s ornamentation and nuances. In the sanjo music of Korea, clear, consistent, recognized melodic and rhythmic structures pass from teachers to students, but each player is expected to exercise great individuality in ornamentation and nuance.

Musical Instruments

Perhaps the strongest case for treating China, Japan, and Korea as a musical region can be made in the related musical instrument types found in the three countries. Long zithers with movable bridges, bowed lutes, transverse and end-blown bamboo flutes, and cylindrical double-reeds are shared by all three countries. Other instrument types are prominent in both China and Japan (three-stringed and four-stringed plucked lutes) or China and Korea (conical double-reed, two-stringed bowed lutes), while still others (such as the bowed zither in Korea and Okinawa) are preserved in one country but are no longer played elsewhere.

Percussion instruments in East Asia tend to be rather specific to individual cultures and to genres within a culture. Virtuoso playing is featured in the music of Korean farmers’ bands and in samul nori, Japanese taiko drumming...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Editorial Board

- Contributing Authors volume 2

- Reviewers volume 2

- Audio Examples volume 2

- 6. The Middle East

- 7. South Asia

- 8. East Asia

- 9. Southeast Asia

- Glossary for Volume 2

- Notes on the Audio Examples

- Index