- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tutankhamen & The Discovery of His Tomb

About this book

The discovery of Tutankhamen's tomb in 1922 aroused unprecedented excitement in the field of Egyptology. In the tomb of a "colourless youth, who reigned for a few years only" were found unmatched riches, the study of which has led to numerous insights into ancient Egyptian civilization. The author of this fascinating text discusses the tomb's discovery, the significance of its discovery and contents, tomb-robbers, and the ethics of desecration.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tutankhamen & The Discovery of His Tomb by Howard Carter,Lord Carnarvon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER V

THE VALLEY OF THE TOMBS

IT was about the year 1500 B.C. that the desolate and impressive ravine which is now known as the Valley of the Tombs of the Kings was chosen by King Thothmes I as the site for his tomb. Ills immediate predecessor Amenhotep I had observed the practice, which had prevailed since the temple was first invented, of building the tomb in association with it. For the temple was a development of the rooms provided at the tomb for the relations of the deceased to make offerings of food and drink to the dead for the essentially practical purpose of maintaining his existence. In these rooms also certain ceremonies were performed from time to time with the object of animating the dead elan (or his portrait statue) so that he could enjoy the food and commune with leis relations. But such functions were also part of the process of conveying “life” to hint and so ensuring the maintenance of his existence.

In course of time as these ceremonies for

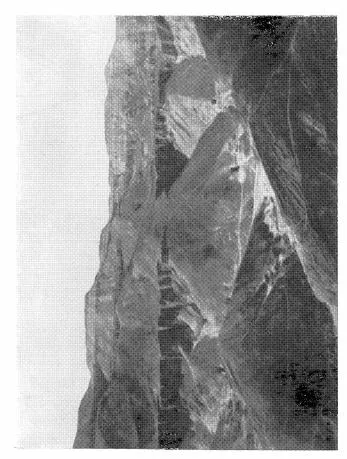

FIG.10 —The end of the desolate Valley of the Tombs of the Kings at Thebes the most impressive site in the whole of Egypt.

conveying sustenance and life to a dead king assumed a wider significance the chamber of offering developed into a temple and a subtle change occurred in the meaning attached to the ritual. For instead of being regarded

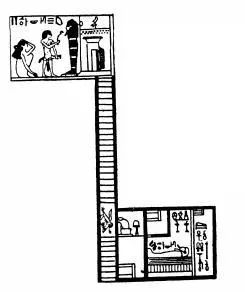

FIG.11 —An ancient Egyptian drawing (circa 1400 B.C.) illustrating the arrangement of the tomb and temple about a millennium earlier. The temple where the relations of the deceased made offerings or animating ceremonies before the statue (or the mummy itself) was then an essential part of the tomb, where the actual body of the deceased yeas laid to rest.

merely as a physical device for conveying food and the essence of life the ceremonies came to be regarded more and more as acts of worship of the dead king. When this happened the close nexus between the temple and the tomb was no longer so essential as it was in earlier times when the ceremonial in the former was intended to vitalize the corpse of the king (or his substitute the portrait statue). But it was not until the closing years of the sixteenth century B.C. (Thothmes I is believed to have died in 1501 B.c.) that the king began to prepare a tomb for himself miles away from his temple. This geographical separation of the temple from the tomb had a far-reaching influence upon the functions of the former, and prepared the way for the modern conception of a house of worship, even though in Europe the ancient conception of the close association of a church and a churchyard (as a burying place) was retained. The practice inaugurated by Thothmes I of preparing royal tombs in the famous Theban Valley lasted from about 1500 B.C. until the end of the twentieth dynasty, about 1090 B.C.

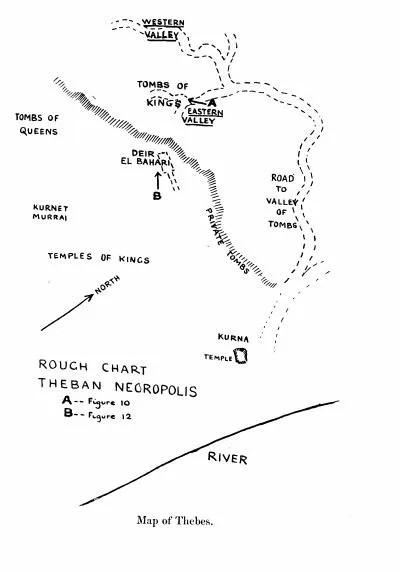

Amenhotep III, who was buried in 1375 B.C., broke away from the observances of his four predecessors who were buried in the Eastern Valley and made his tomb in the Western Valley ; and his famous son and successor, Amenhotep IV, the heretic king Akhenaton, made the more daring innovation of preparing a tomb at his new capital, the City of the Horizon of Aton, on the site of the modern Tell el Amarna. It was a rock-cut tomb in the mountains about seven miles to the east of his new capital—which Akhenaton built midway (p. 22) between Thebes and Memphis, the ancient capitals of Upper and Lower Egypt respectively. There he seems to have been buried in the red granite sarcophagus that is now broken into fragments ; but his son-in-law Tutankhamen, when he reverted to the orthodox religion of Thebes, thought it proper to remove the mummy of his father-in-law from the City of the Horizon to the Theban necropolis and made for it the resting place in the Valley of the Tombs, which was discovered in 1907 by Mr Arthur Weigall, who as Inspector of Antiquities for Upper Egypt was supervising the excavations endowed by the late Mr Theodore M. Davis.

The fate of the mummy of Akhenaton’ s successor Smenkhara is unknown: but Tutankhamen came after him, and Mr Howard Carter’ s discovery has shown that he displayed his return to strict orthodoxy by making his tomb in the Eastern Valley among the worshippers of Anien. For some reason which has not been fully elucidated, his successor Ay made his tomb in the Western Valley and so was laid to rest alongside Amenhotep III, whose Minister he seems to have been during

Map of Thebes.

his life. He is supposed by some historians to have been the father or the foster-father of Nefertiti, the wife of Aklenaton.

Until the discovery of Tutankhamen’ s tomb in the Eastern Valley last November it was believed (by Sir Gaston Maspero and others) that it would be found in the Western Valley. Until then Ay’ s was the earliest royal tomb, after that of Amenhotep III, to be discovered, and as they were in the Western Valley, it seemed probable that Ay’ s predecessor Tutankhamen-had also been buried there. But when making the secondary tomb for Akhenaton in the Eastern Valley he seems to have made his own tomb there also, and so resumed the old practice, which was observed by all his successors for two and a half centuries with the exception only of his successor Ay.

This wonderfully impressive gorge (Fig. 10,p. 66) is known to the modern Egyptians as the Bab (or Biban) el Mohch,the Gate (or Gates) of the Kings. It was known to travellers ever since it was made into the royal necropolis, and Greeks and Romans marvelled at the wonderful tunnel-like tombs there, as generations of tourists have done ever since. Strabo mentions his having seen forty of these tombs, but it is not clear from his account whether he did not include those of the Western Valley and perhaps the Tombs of the Queens and others.

Modern research was inaugurated by the traveller Belzoni who opened the tomb of Seti I in 1819 and described the pictures on its walls (Fig. 20 is copied from his notebook) before they were damaged or destroyed. He brought to London the magnificent “alabaster” sarcophagus of this pharaoh, which is now in Sir John Soane’ s museum in Lincoln’ s Inn Fields.

The year 1881 will always be memorable for the earliest discovery of Royal mummies. Five years later, when the wrappings were removed from such pharaohs as Seti I and Rameses II, modern men had the novel experience of gazing upon the actual faces of these famous rulers of the remotely distant past, whose exploits had resounded through the civilized world for thirty centuries and more. On several occasions in former years the discovery of Royal mummies had been reported ; but in every case further investigation failed to justify such claims, for they proved to be merely intrusive burials of unknown people belonging to times much later than the rifled tombs in which they were found. Examples of such mistakes in identification are the eighteenth dynasty mummy, now in the Cairo Museum, which was found in a pyramid at Sakkara, and at one time was supposed to be the son of King Pepi, of the sixth dynasty ; and the skeleton (not a mummy) in the British Museum from the pyramid of Mykerinus, which has repeatedly been referred to as the bones, or even as the mummy, of that pharaoh.

The discoveries made in the famous cache at Deir el Bahari in 1881, and in the Valley of the Tombs of the Kings during the decade 1898–1908, revealed the only actual mummies of members of the royal family so far recovered, although the skeletons of niuch earlier members of the ruling house were found by M. de Morgan in the pyramids of Dashur nearly thirty years ago.

Long before the recovery of the actual bodies of these famous rulers the statues and bas-reliefs of some of them had familiarized us with their appearance ; and inscriptions on their monuments and the ancient writings of the Egyptians and their neighbours had made us acquainted with certain of their exploits. The plundered tombs of some of the great kings of the eighteenth and nineteenth dynasties

FIG.12 —An old photograph of the great cliffs behind Deir el Bahari, showing this temple as it was in 1881 before it was excavated. The royal mummies were hidden in a cleft in these cliffs.

have been known and visited by tourists from the times of the Greek domination of Egypt, and contemporary documents refer to others. M oreover, twenty years before the mummies themselves were revealed, the dealers in antiquities began to offer for sale a series of papyri (most of which carne to this country) giving accounts of the desecration of the royal Theban tombs.

Tomb-robbers’ Confessions

In the late Lord Amherst’ s collection, which was recently sold in London, there was a judicial papyrus of the reign of Rameses IX (about 1125 B.C.), reporting the trial of eight “servants of the High Priest of Amen,” who were arraigned •for plundering the tomb of King Sebekemsaf of the thirteenth dynasty. The written depositions of the prisoners set before the pharaoh by the vizier, the lieutenant, the reporter, and the mayor of Thebes were translated by Professor Percy Newberry in these terms : “We opened the coffins and their wrappings, which were on them, and we found the noble mummy of the king. There were two swords and many amulets and necklaces of gold on his neck : his head was covered with gold. We tore off the gold that we found on the noble mummy of this god [i.c. the dead king who was identified with Osiris]. We found the royal wife also. We tore off all that we found from her mummy likewise, and we set fire to their wrappings. W e took their furniture of gold, silver and copper vases, which we found with them.” The prisoners who made this confession were found guilty, and sentenced “to be placed in the prison of the temple of Amen,” to await “the punishment that our lord the pharaoh shall decide.” There are several other famous papyri reporting trials of desecrators of the royal tombs. In the Abbott papyrus (in the British Museum) inspectors submit a report on the tombs that were said to have been plundered, but the only one that had actually been robbed was that referred to in the confession just quoted from the Amherst papyrus. The two Mayer papyri in the Liverpool Free Public Museums relate to plundering in the Valley of the Tombs of the Kings. One of these is of special interest at the present moment because it relates to the violation of the tomb of Rameses VI, which is immediately above that of Tutankhamen. The robbers were discovered as the result of quarrels among themselves about the division of the spoil. This was one Of the most disgraceful incidents in the whole history of tomb-plundering. The robbers, in their haste to get at the gold and jewels upon the mummies, usually chopped through the bandages. and mutilated the mummy in the process. But when, in 1905, I removed the wrappings from the mummy of Rameses VI (which in ancient times had been removed to the tomb of Amenhotep II, where it was discovered by M. Loret in 1898), the body was found to be hacked to pieces. This was no mere accidental injury, but clearly intentional destruction of a malicious nature. It makes one realize the sort of vandalism Tutankhamen’ s tomb so narrowly escaped.

Hiding the Mummies

The discovery of the royal mummies in 1881—and this applies with special force to the remains of the famous pharaohs Seti I and Rameses II —gave us the other side of the story, for it revealed the measures taken to protect the bodies of these kings from further injury, and the persistence with which the protectors of the tombs moved the mummies from one place to another in their endeavour to save them. Tiue condition of affairs revealed in the tomb of Tutankhamen brings proof of what has long been suspected, that the work of the plunderer began soon after the closing of the chambers. But during the twentieth and twenty-first dynasties, when there was a rapid weakening of the Administration, tomb-robbing assumed proportions it had never attained before. The record inscribed upon the coffins of Seti I and Rameses II throws a lurid light on the extent of this loss of control. For a century and a half their mummies were moved from one hiding-place to another in the attempt to secure their safety. The mummy of the great Rameses was moved to the tomb of his father, Seti I, whose body for some time remained in its own alabaster sarcophagus, which is now in Sir John Soane’ s Museum in Lincoln’ s Inn Fields. But in the reign of Siamon (976–958 B.c.) the two mummies were hidden in the tomb of a queen called Inhapi, and about ten years later were moved again, this time to a tomb that had been originally prepared for Amenhotep I at Deir el Bahari. Here they, together with more than thirty other royal mummies, remained undist...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- The Kegan Paul Library of Ancient Egypt

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

- PREFACE

- BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE

- I. INTRODUCTORY

- II. EXPLORATION OF THE THEBAN TONIES OF THE KINGS

- III. TUTANKHAMEN

- IV. THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE DISCOVERY

- V. THE VALLEY OF THE TOMBS

- VI. THE STORY OF THE FLOOD

- VII. GETTING TO HEAVEN

- VIII. THE ETHICS OF DESECRATION