![]()

IV. The Advent of Multinationalism

TOWARDS WORLD MONIES

The sixties produced the first international currencies and money markets. The Eurodollar, invented by the USSR and developed by Wall Street, expanded into a $50 billion pool. Eurobonds (denominated in dollars) amount to 2 billion annually and the creation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRS) (about $6 billion to date) within the International Monetary Fund helped to provide fillips to scarce world liquidities and reserves. The growth of total world exports to over $260 billion annually all but submerged the obsolete gold-exchange monetary standard. It revealed the fiction of sterling as an international currency and the fragility of the ratchety international monetary system—already a museum piece. The ratio of reserves to imports in the world fell from 74% in 1954 to less than 30% in 1970. But needs beget means, and new sources of liquidity were created to lubricate world trade and global profit-making, at least temporarily.

One of the side effects of this ‘new money’ is that national interest rates intended to meet the needs of domestic money and credit policies have lost a great deal of their autonomy and their effective range of float. The thrust of ‘hot money’ around the world; the hedging by world corporations against threatened currencies to protect vast, accumulated investment funds from erosion due to inflation or devaluation; the placing of billions of dollars, pounds, or francs on the short-term and ‘spot’ money markets by companies at high rates—these are other new, global monetary practices with which domestic management of money and credit must contend.

Corporate money management has become an important feature of modern finance. Some companies, like Ford, GM and the oil giants such as Shell and the Standards, have top executives in charge of placing their ‘mise’ on the grand prix hot-money circuit. The function of the corporate money manager is to follow markets and determine the best optimal mix for placing and recalling funds, and borrowing and investing short-term assets. These managers in effect put disposable money to work to earn the best yields until its number is called for the long-term input. An international gulf-stream of hot money, billions of dollars long and wide, is coursing around the national money markets of the world in the direction from low to high interest rates, raising and and lowering them continuously, usually in a contrary direction to domestic policy.

THE NEW INTERNATIONAL ECONOMY

The multinational company is creating the outlines of a genuine global economy. By 1975, nearly 35% of the Western world's non-US production will be accounted for by American subsidiaries or American-associated firms. Direct US investment in Europe rose from $6.7 billion in 1960 to over $21 billion in 1970—an increase of over 220%. In 1970, US corporations’ subsidiaries increased their foreign plant and equipment expenditures by $13.2 billion—22%over 1969—and are expected, according to official US estimates, to increase it by 16% to nearly 15.3 billion in 1971. The larger part will be in Western Europe. In 1969 this expenditure amounted to only $10.8 billion and in 1968, to $9.4 billion. Since the end of World War II, American firms have established over 8000 directly-owned subsidiaries abroad.

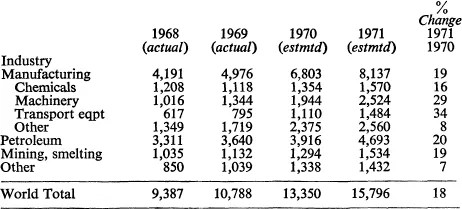

During the last ten years, the book value of American investment abroad more than doubled, from $32 billion in 1959 to $70 billion in 1969 and $80 billion in 1970. By the end of 1971 US overseas investment will exceed $90 billion. In 1970 it rose by 22% to a record annual amount of $13.2 billion. In addition, about $1.5 billion a year has been added through reinvesting the profits from foreign subsidiaries. Foreign portfolio investment in securities is over $19 billion. Together, US foreign direct spending, reinvestment of profits and portfolio investments amount to around $120 billion. The sales generated by these productive assets is well over $250 billion a year compared to $40 billion in exports. By conservative estimates this is expected to reach $275 billion a year by 1972 while exports will rise to $45 billion. Tables IV.1 and IV.2 summarize expenditures for various industries worldwide and for manufacturing investment in various regions and countries:

Foreign direct investment has been increasing at a rate of between 12% and 15%. On the basis of present trends this figure will rise to over 20% by the end of the decade. By contrast, GNP of the world's principal industrialized countries will increase at between 3% and 5%. This will intensify capital exports and exercise increasing pressure on the world's monetary reserves, given that a growing part of total productive investment will consist of capital raised in one country and put down in another.

The Stake of U.S. Business Abroad

Data: Commerce Dept.

Fig. IV 1

TABLE IV.1. Actual and Estimated Plant and Equipment Outlays by Industry (in $ millions)

TABLE IV.2. Actual and Estimated Manufacturing Outlays by Area (in $ millions)

Source: US Department of Commerce

Total sales of foreign subsidiaries around the world arising out of $180 billion of book value assets is already over $100 billion greater than the total volume of world exports. The sales of American firms abroad are more than five times the value of the country's exports. It is expected to rise to nine times by 1975. American writer Ludwell Denny sums up the philosophy behind this drive: ‘We are not without cunning. We shall not make Britain's mistake. Too wise to govern the world, we shall merely own it.’

LE DÉFI EUROPÉEN

By 1975, just under a quarter of US GNP will be produced by European and Japanese firms. The great investment thrust of European enterprises in the seventies will be to the US, the world's biggest and most profitable market, thus complementing the efforts of American firms in Europe, including the US charter members of the European Common Market.

Foreign direct investment in the United States is expected to rise steeply as corporations abroad seek to enlarge their production and develop the organizational and financial strength needed to participate directly in the difficult but highly lucrative US market.

EXPERT OPINION

Herman Josef Abs

President of the Deutsche Bank and 18 other German companies

One of Europe's most powerful pillars of finance

‘This workshop that is the Federal Republic of Germany only works and works without providing itself with adequate means to face the necessities of 1980 to 1990.’ American firms implanted abroad, he said, produce four times more than the exports of companies located within the country. He declared that Germans should stop lending money abroad and create enterprises instead.

Giovanni Agnelli

President of FIAT

‘US corporations are the only true European Multinational enterprises.’

M. Jacques Chirac

French Secretary of State for Economy and Finance

‘We have a rise in the rate of industrial investment for 1970 in excess of 20%. France has been surprised by the international boom.

‘All this because one didn't invest at the appropriate moment. One is precipitating therefore towards more investments in a period of high expansion, which serves to accelerate the overheating. . . .

‘Equilibrium of the balance of payments and even its surplus is another necessity. It is in effect indispensable to constitute reserves in order to dispose of the necessary capital for our overseas expansion.’

By the end of 1969, such investment reached an $11.8 billion total and for the first time had increased more than $1 billion in a single year—after being only moderately short of this figure in 1968. A figure of nearly $12 billion in foreign investment in the United States today may not seem important compared with a book value of more than $80 billion for US private direct investment abroad. But foreign investment in the US is growing at a considerably faster pace at present than US investment overseas. These figures apply only to direct investments in manufacturing enterprises, and do not include portfolio or real estate investment. Today more than 700 US manufacturing enterprises are owned wholly or in part by almost 500 foreign companies. Foreign investments cover a wide spectrum of industrial lines. Particularly prominent is the chemical and pharmaceutical industry that has attracted large-scale Swiss and German investments. Historically, the largest aggregate investment has come from the United Kingdom, which accounts for about $3.5 billion of the total and for about 107 enterprises in the United States. Canada is next with $2.6 billion and 114 firms. The Netherlands follows, with $1.9 billion and the distinction of having a greater investment position in the United States than American firms have in the Netherlands. Still relatively modest in aggregate terms, investment from Germany and Japan is increasing rapidly. Investment from Japan to date has been principally in developing sources of raw materials for its own industry, mainly in Alaska.

ICI announced in April 1971 that it was going to take over the US Atlas Chemical Industries for $163.9 million in cash. In announcing the deal, ICI Chairman, Jack Callard, said the merger was the most important single step ever taken by ICI in the Western Hemisphere. Especially interesting is the fact that the acquisition will be financed with funds from non-sterling sources, assisted by a consortium of American banks. Atlas, a speciality chemical and pharmaceutical firm, had sales of $155 million in 1970. Mr Callard said Atlas provides ‘the requisite strength in certain market areas and the very necessary management skills to complete the base from which major expansion will take place. This combination is an essential part of the policy designed to create a strong US company fully capable of developing on a broad basis from its own and ICI’s innovations and research discoveries.’

The combined company is to be called ICI America Inc.

The Celanese Corp., another top US Chemical firm, is known to be discussing a joint venture with ICI to build a plant in Britain. John Brooks, President of Celanese, said that ICI now resells Celanese chemical products in England.

EVEN SMALL COUNTRIES HAVE GONE MULTINATIONAL

Long renowned as a host country for international banking and holding companies, Switzerland (which has 6700 holdings enjoying its tax-haven privileges) is less known for the fact that i...