- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Rural Depopulation in England and Wales, 1851-1951

About this book

First Published in 1998. This book aims to accommodate for the little attention paid to the needs of the people living in rural Britain. The author argues that there has hardly been an attempt to describe the impact of new machines and of new wage-levels on farm and village. The title sets out to answer two key questions: can the traditional pattern of settlement survive, and has depopulation in the truly rural areas gone so far as to undermine the viability of the small villages and hamlets?

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Rural Depopulation in England and Wales, 1851-1951 by John Saville in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

I. THE GROWTH OF AN URBAN SOCIETY

In the hundred years following the application of the rotary movement to the steam engine1 Britain made the transition to the ‘industry state’. Economic activity from being centred upon agriculture and allied industries now became concentrated in the areas of coal-mining and the great industrial and commercial towns. Agriculture steadily lost its predominant place in the economy. In 1851 agriculture employed a quarter of the males aged 20 and over2 while by the end of the century the proportion (aged 14 and over) had declined to under 10 per cent. The British economy came to live by the export of manufactured goods, capital and economic services, from the proceeds of which an increasing volume of food-stuffs and raw materials was purchased. The repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 underlined the shift in economic emphasis which had taken place during the first half of the nineteenth century whereby Britain had become one of the foremost industrial powers3 and the greatest trading nation in the world.

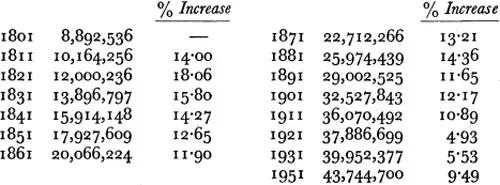

A central feature of the industrialization of Britain during the past century and a half has been the rapid increase of population. Before 1700 population growth in Britain was slow. During the eighteenth century the rate of population growth increased quite sharply, in a number of European countries as well as in Britain, and in this country the increase in numbers over the whole century was around 50 per cent.1 Towards the end of the eighteenth century the decline of the death-rate together with the maintenance of a high birth-rate combined to produce an unparalleled rate of natural increase,2 and the Census of 1801, followed by regular decennial Censuses, allowed for the first time a reasonably accurate measurement of population growth.3 No decade in the nineteenth century showed less than a 10 per cent increase in total population compared with the previous decade, despite the considerable emigration to foreign countries which continued throughout the century and into the twentieth. The population of England and Wales doubled during the first fifty years of the nineteenth century and doubled again by 1911. Thereafter, although total numbers continued to increase in the twentieth century, the rate of population growth has been much slower, a demographic characteristic common to almost all the economically advanced countries.1

Table I

POPULATION 1801-1951. ENGLAND AND WALES*

* 1801-1931: Census of England and Wales, 1931, General Report, p. 22. 1951: Census 1951, Great Britain, One per cent Sample Tables, Part 1, Table 1.2.

Throughout the nineteenth century people were increasingly congregating in the urban centres of commerce and industry as well as in the areas of coal-mining. For most of the large industrial towns of today the most rapid rate of population growth came in the first half of the nineteenth century,2 and by 1851 the Census was noting that just over half the total population of England and Wales were living in urban areas.3 The growth of urbanization has continued until the present day, and by 1951 some 40 per cent of the population lived in six great industrial and commercial conurbations.4 As urbanization developed, the proportion of the population who lived in rural areas correspondingly diminished, although a precise and accurate definition of what constitutes a rural district is not easy, and the difficulty of definition increases as we approach our own times.5 But leaving aside for the moment the problem of the precise delimitation between urban and rural areas, we can say that whereas a hundred years ago the populations of these two divisions were approximately equal, in the last thirty years about 80 per cent of the population have lived in urban districts and the remaining 20 per cent in rural districts. That is the broad measure of the shift from rural to urban within our society consequent upon the industrialization of its economy.

Urbanization is not to be confused with industrialization, and the former can, within certain limits, develop within a nonindustrial society; but in the conditions of nineteenth-century Britain, the rate of growth of the urban areas can be broadly correlated with the development of industrial capitalism. Again, the development of industrial capitalism and the growth of the urban areas in the first half of the nineteenth century must not be regarded as synonymous terms for the growth of the factory-type of industrial organization. The factory won a surprisingly slow victory over older forms of industrial organization and it was only in the closing decades of the nineteenth century that it became the dominant form in a majority of industries.1 But with these qualifications, the growth of the towns in Britain during the nineteenth century is an index to the development of the ‘industry state’ and the social relationships which accompanied the new industrial order.

The growth of towns in the nineteenth century was a product of three factors: one was the high rate of natural increase of the urban population, the second was the continuous inflow of population from the rural areas and the third was the immigration into England and Wales from Scotland and especially from Ireland, and to a lesser extent from the outside world. The influx from the rural areas into the rapidly growing urban agglomerations remained of major importance for the whole of the nineteenth century and continued in the twentieth century,2 although as the towns grew in size the proportionate effect of the rural inflow became gradually lessened. Within the urban areas the rate of natural increase continued at a high level to the end of the nineteenth century. The third factor, immigration into England and Wales from outside territories, was never as important as either of the other two factors, and after the peak of Irish immigration was passed, around the middle of the century, it became, except for one or two individual cities, of steadily diminishing significance.1

The acceleration of the movement of country people to the towns occurred within the same historical period as that normally described as the Industrial Revolution, although before the early nineteenth century the statistical basis for precise analysis is absent. From about the 1780s, that is, the pace of migration from the rural areas quickened, and the absolute growth of rural populations was, as a result, much slower than for the urban populations. It was not, however, until the second quarter of the nineteenth century that the rural outflow began to affect the absolute size of the rural communities. At some point between 1821 and 1851 a considerable proportion of the villages and rural parishes of England and Wales passed their peak of population and entered upon an almost continuous decline of their total populations; for the rest of the rural areas, their curve of peak and decline was set in the second rather than in the first half of the century, but few parts of the country failed to conform to the pattern.2 By the end of the nineteenth century the problem was recognized as a serious one; and against the background of agricultural depression, investigations and analyses of rural depopulation multiplied,3 without, however, any significant effect upon Government policy. In the twentieth century there has been no change in the general tendencies towards depopulation of the rural areas, although a number of the factors involved have either changed or in some ways become more complex. One striking difference has been the slowing down in the rate of population increase. Whereas no period of twenty years before 1901 had an increase in total population lower than 25 per cent over the previous twenty years, in the first two decades of the present century the increase had dropped to 16 per cent, and between 1921 and 1941 the estimated increase was just under 10 per cent. Only in the 1940s was the decline in the rate of increase arrested, although for the years 1931 to 1951 the proportionate increase amounted to no more than for the years 1921 to 1941. The general decline in the natural increase of population, and ignoring for the moment differential fertility and mortality rates between town and country, inevitably reduced the size of the surplus population available in the rural areas for migration to the towns. Unless the disintegration of the rural economy was proceeding at a faster rate than hitherto, the flow of country people to the towns would necessarily become smaller. For this, and for other reasons discussed later in this study, the exodus from the countryside has continued at a slower rate in the twentieth century,1 and the proportion of the population living in rural districts has changed only slightly during the past thirty years. Taking England and Wales together, the rural sector appears to have achieved a relative stability during the last three decades, and at the ratio of 80 : 20 some sort of equilibrium seems to have been reached between the urban and the rural areas. This stability is, however, only a surface appearance, and it conceals the disintegrating factors which are still working within the rural economy and which have been carried over from the nineteenth century. The lines of demarcation between town and country have become increasingly difficult to define and the pattern of settlement has in certain respects become more complex, but the processes of depopulation have continued, and the more rural an area, the greater is the likelihood that it has steadily lost population up to the present day.

The causes of rural depopulation have not altered in any significant way during the last century and a half. A change in emphasis has naturally occurred between the various factors involved, and both at different times and at different places the local or regional causes of the rural exodus will lay a different stress upon individual forces of expulsion. The basi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Tables

- Foreword by Leonard Elmhirst

- Introduction

- Chapter One The Historical Background

- Chapter Two Internal Migration and Rural Depopulation

- Chapter Three Migration Differentials

- Chapter Four Some Aspects of the Contemporary Problem

- Chapter Five A Study of the South Hams

- Index