- 164 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Shakespeares Last Plays

About this book

This is Volume VI in the selected works of Frances Yates, providing a new approach to Shakespeare's last plays. First published in 1975, these are a collection of lectures that offer the new thinking about certain ideas concerning Shakespeare's relation to the problemsand thought currents of his times.

Information

1

The Elizabethan Revival in the Jacobean Age

The consistent and complicated propaganda which had been built around Queen Elizabeth I, had glorified her as the Virgin representative of imperial reform. The Tudor reform of the Church by the Monarch was based on the traditions of sacred imperialism, on the right of emperors in the Councils of the Church. Sacred imperialism was the dominant theme in the propaganda for Elizabeth I, as has been demonstrated in Astraea. With this theme of monarchical reformation was associated the chivalrous romance enacted around the Queen by her knights. Through the mythical descent of the Tudors from King Arthur, the Tudor imperial and Protestant reform of the Church could be presented in terms of a pure knighthood obeying the behests of a Virgin Queen and spreading the light of her rule through the world.1 Thus there was built in to the basically Protestant position of the Queen as representative of a pure reformed Church which had cast off the impurities of Rome, this aura of chivalric Arthurian purity, of a British imperialism, using British in the mythic and romantic sense which it had for the Elizabethans. The Virgil of the Elizabethan religious imperialism immortalised its chivalric modes of expression in The Faerie Queene.2

James I, when he succeeded to Elizabeth’s throne, tried also to succeed to her symbolism. He claimed the descent, through his Tudor ancestor, Henry VII, from King Arthur, and Arthurian associations were used in celebrating the union of Scotland and England brought about through his accession to the two thrones.3 James as ruler of a united Britain was a new Arthur of Britain. Nevertheless, there were profound differences between the Tudor religious and chivalric imperialism inspired by the Virgin Queen and the more limited conceptions of James. The Elizabethan type implied the establishment of a universal pure reform, a purified order and peace which could appeal to chivalric religious traditions to maintain it. For James, as has been said, ‘his British claim became entangled with his concept of divine right which was far more partisan than the broad heavenly blessing ascribed to the Tudors’.4 The Jacobean peace — and James forever emphasised himself as a peacebringer and peacemaker — was an avoidance of conflict. It carried within it no mission of universal reform or support of European Protestantism.

The uneasiness of James’s reign largely arose through this confusion. On the one hand, James appeared to be, both at home and abroad, the successor of Elizabeth, not only to her throne but also to her politics and symbolism, the representative of Protestant monarchy, the leader of Protestant Europe. Yet, though in the beginning of his reign James appeared to be resuming the Elizabethan role of championship of religious reform, of friendship with Protestant princes abroad, at heart he was deeply afraid of the Catholic Spanish-Hapsburg powers, and was bent on appeasing them.

Surviving Elizabethans of the old school, like Philip Sidney’s friend, Fulke Greville, or like Walter Raleigh, were acutely aware of the change in temper under James, and anxious about it. And anyone could see the profound difference between the tone of Elizabeth’s court, with its emphasis on chastity and dignity, and the court of James. The Elizabethan chivalric Puritanism had suffered an eclipse; the Philip Sidney tradition was in abeyance.

The magical and scientific tradition stemming from John Dee, formerly philosopher-in-chief to Queen Elizabeth, was also in abeyance and discouraged. The discouragement of Dee had begun in the last years of Elizabeth’s reign, after his return from his mysterious activities in Bohemia. He appealed to James, after his accession, to defend him from charges of black magic, but in vain.5 He died in 1608 in great poverty. Dee had been a propagator and theorist of the Elizabethan type of British imperialism; the neglect and discarding of Dee was also, in effect, a denial of a deep-seated Elizabethan movement, with which Philip Sidney had probably been in sympathy.

Yet there was also in this early Jacobean period a movement which might be called an Elizabethan revival, and which was particularly associated with James’s eldest son, Prince Henry. From a very early age, this young man had shown signs of remarkable determination of character and capacity for leadership. Prince Henry did not leave a strong mark on history because he was not destined to live to make that mark. He died on 17 November 1612, at the age of nineteen, only two years after becoming Prince of Wales amid general acclamation. We can never know what difference the early and most unexpected death of this young man made in history.

Though the panegyric of Prince Henry by his tutor, Charles Cornwallis,6 published in 1641, may err on the side of exaggeration, the main lines of his characterisation of the prince are corroborated from other sources, particularly the despatches of the Venetian ambassador, who admired him greatly.7 Cornwallis describes him as grave beyond his years, reserved and secret. He gathered about him a large household of young men, more than five hundred, whom he led in virtue and discipline and military sports. He was not lascivious, always decorous in behaviour, and singularly graceful in his movements. He was genuinely pious and strongly Protestant, though, according to the Venetian ambassador, he would not allow anyone to call the Pope Antichrist in his presence.8 The Venetian ambassador hints that Prince Henry entertained schemes of very great weight and scope, that he believed that a way could be found for ending ‘the jars in religion’.9 He also believed in working for strong military and naval preparedness. He and his followers engaged constantly in martial exercises. He was interested in military art, mathematics, and fortification,10 and particularly interested in shipbuilding. He encouraged Phineas Pett who built for him a ship of war. On military and naval matters he consulted Walter Raleigh, who fared no better than John Dee in the Jacobean age, for James kept him in prison. Everyone knows Prince Henry’s remark, that only his father would keep such a bird as that in a cage.

As this remark implies, there was a marked contrast between Prince Henry and his father in character, and in what would now be called public image. The image of Prince Henry, the stern young prince exercising for some coming duty, has about it an aura of Philip Sidney which could never linger over James. Prince Henry’s court was more like a continuation of Elizabethan traditions than the court which we think of as Jacobean.

Prince Henry would appear to have been building himself up, and being built up by others, as a leader of Protestant Europe in the great confrontation with the Spanish-Hapsburg powers, the threat of which loomed over Europe in the early years of the seventeenth century. We cannot quite know how this grave and secret young man proposed to deal with it. He certainly meant, unlike his father, to take a strong line. Whether he hoped through a great Protestant alliance — he was in contact with Christian of Anhalt and other European Protestant leaders11 — to break the Hapsburg power and after having done so to end ‘the jars in religion’ through some wide-ranging solution, remains a question which his early death, and all those papers which he destroyed before his death, leaves unanswerable. Would Prince Henry, who might have seemed to enthusiasts something like a cross between Henry V and the Earl of Essex, have embroiled his father’s ‘Great Britain’ in a war which would have destroyed it, as other European countries were to be destroyed in the Thirty Years’ War ? Or would he have taken action which would have averted that war and destroyed its causes, as some people – perhaps wrongly – believed possible? Prince Henry is a great historical question mark, comparable to another Henry, Henry of Navarre, that is Henri IV, King of France, whose assassination on 14 May 1610, on the eve of setting out for Germany on some great military enterprise, leaves unanswered the question of what exactly it was that he intended to do, and whether, if he had succeeded in doing it, the whole course of European history might have been different.

1a Prince Henry. Miniature attributed to Isaac Oliver. Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

1b Prince Henry. Portrait attributed to Robert Peake the Elder. Magdalen College, Oxford

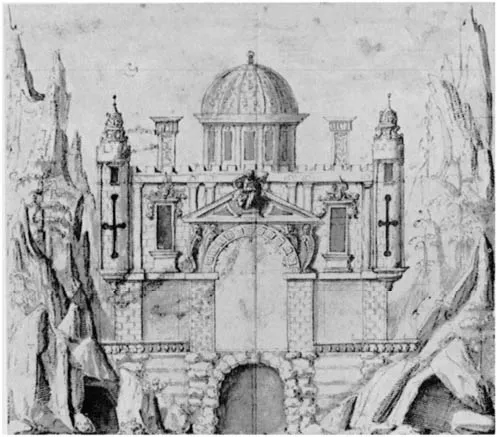

2 Inigo Jones. St George’s Portico, ‘Prince Henry’s Barriers’. Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth

3 Inigo Jones. Ruined Palace of Chivalry, ‘Prince Henry’s Barriers’. Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth

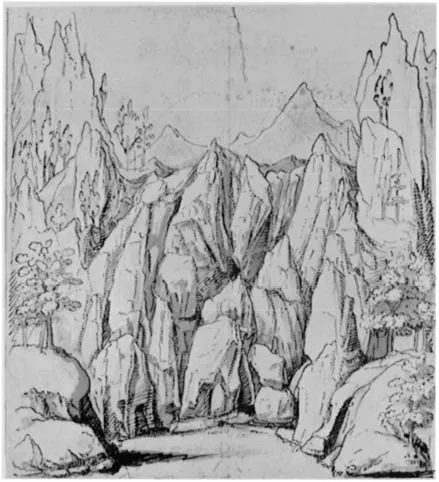

4 Inigo Jones. The Rock, ‘Masque of Oberon’. Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth

5 Inigo Jone’s. Oberons Palace. ‘Masque of Oberon’. Devonshire Collec Chatsworth

6 Title-page, Michael Drayton, Polyolbion, London, 1612

7 Prince Henry. Engraving in Michael Drayton, Polyolbion, 1612

8 The ‘Rainbow Portrait’ of Queen Elizabeth I. Hatfield House

In fact, there is a close connection between the two question marks, for Henri IV was assassinated just one month before the young Prince Henry was created Prince of Wales. Henri IV had been the leader to whom...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Plates

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 The Elizabethan Revival in the Jacobean Age

- 2 Cymbeline

- 3 Henry VIII

- 4 Magic in the Last Plays: The Tempest

- 5 A Sequel: Ben Jonson and the Last Plays

- Epilogue

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Shakespeares Last Plays by F.A. Yates,Frances Yates in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.