![]()

Post-Kyoto climate governance

The lack of international action on human induced global climate change

The human induced global climate change is a complex challenge that will determine the future of human civilization and its place in the broader evolution of life on the planet earth. Despite persistent warnings from climate change scientists (IPCC 1995, 2001, 2007) and mounting evidence of disruptive climatic changes all over the planet (IPCC 2012), the international community of nations has failed to take meaningful action in proactively reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions that are primarily responsible for human induced climate change. Based upon the agreements reached at the first Rio summit in 1992, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was given a rather vague mandate to prevent global climate change from reaching any “dangerous” levels. The lack of any democratic system at the international scale in this so-called “age of anthropocene” has further complicated the mandate of the UNFCCC.

The modest success attained by the UNFCCC process through the Kyoto Protocol (KP) in mandating approximately 5 percent reduction in the GHG emissions from the industrialized countries by 2012 below 1990 levels has been blown up due to the non-participation of the largest GHG emitting country (the United States) in ratifying the Kyoto Protocol, the withdrawl of another large GHG emitting country from the KP (Canada) after it realized it cannot meet its agreed upon GHG emission reductions and the issuance of so-called “hot air” emission credits to Russia and other eastern European countries. The lack of any meaningful mandatory GHG reductions from the so-called industrializing nations, such as the BRICS countries (Brazil, India, China, and South Africa) further weakened the potential of KP in reducing planetary scale GHG emissions. Consequently, human induced global climate change continues to take place largely unmitigated except for brief periods of global recession.

Amidst calls about the failure of Kyoto Protocol to regulate the growth of GHG emissions (Cass 2006; Harrison and Sundstrom 2007), a plethora of policy architectures have been proposed for designing an international post-Kyoto climate change governance regime. Bodansky et al. (2004), for example, provide an overview of sixty-four policy architectures that have been proposed in the recent literature. Different subsets of these sixty-four post-Kyoto policy architectures have been evaluated on the criteria of equity and justice (Baer 2002; Klinsky and Dowlatabadi 2009); fairness principles and operational requirements (Torvanger and Ringius 2002); environmental outcome, dynamic efficiency, cost effectiveness, equity, flexibility in the presence of new information, and incentives for participation and compliance (Aldy et al. 2003); cost-effectiveness, and compliance and participation (Barrett and Stavins 2003); regional representation of proposal authors (Kameyama 2004); quantitative and non-quantitative approaches (Philibert 2005); credibility, stability, flexibility, and inclusiveness (Biermann 2005); institutional design, participation, flexibility, and quantity versus prices (Guesnerie 2006); and technological cooperation (De Coninck et al. 2008). All of these criteria are perhaps critical in comparing post-Kyoto global climate governance and policy architectures, yet there are no constitutional, legal, institutional or moral reasons to prefer one set of evaluation criteria over the others. In other words, the complexity of orchestrating a global governance and policy regime poses fundamental challenges, as it has been demonstrated in the endless negotiation processes that have taken place without any meaningful action since the early 1990s.

The design of a post-Kyoto international climate governance regime under different policy architectures will, it has been argued and counter-argued during these negotiations, require a choice between binding versus non-binding and grandfathering versus per capita or some other complex decision heuristic. The Kyoto Treaty employed a grandfathering decision heuristic to set up binding emission reduction targets. A grandfathering decision heuristic establishes a baseline year (1990 for Kyoto) and participating nations agree on binding targets and deadlines to reduce GHG emissions to a certain percentage below the baseline year, which is a 5.2 percent below 1990 levels for certain developed, so-called Annex I, countries by 2008–2012 under the Kyoto Protocol (UNFCCC 1998: Appendix B). The grandfathering decision heuristic has been criticized by the overwhelming majority of developing nations (including large GHG polluters such as China and India) for granting a “free ride” to the industrialized nations for the GHG emissions that were either emitted prior to the baseline year since the onset of the Industrial Revolution in the 1750s or that are being emitted well above global per capita averages since the baseline year. Some of these GHG emissions will stay in the atmosphere for hundreds and thousands of years and, representatives of developing countries argued, any “equitable” GHG emission reduction plan must take into account these GHG emissions that were an unintended consequence of the industrialization process that brought overwhelming development to the industrialized world.

The “grandfathering” decision heuristic is not an acceptable option for many developing countries for a post-Kyoto climate governance regime. Instead of the grandfathering decision heuristic, GHG emission caps on a per capita basis appear more favorable to many developing country representatives of international climate policy negotiations because a per capita decision heuristic will arguably preserve their right of development. In contrast, many developed countries, especially the United States, Canada and Australia, have consistently shown their disagreement with the per capita decision heuristic. These developed countries argued that per capita decision heuristic will not only result in more stringent caps on the developed nations with higher historical GHG emissions, but it will also allow for larger populations of the developing countries. In fact, some of these high emitting countries, defined in this book as the countries that emit statistically significantly higher GHG/capita emissions than the global average for a predefined period, have even threatened to boycott any treaty that imposes binding GHG emission reductions in post-Kyoto phase. Were these high emitting countries to agree on a binding regime, the methodological dilemma surrounding the choice of one or another decision heuristic will require a resolution for designing a post-Kyoto governance regime.

An interdisciplinary and meta-theoretical perspective

The tension between developing and developed countries in the design of binding versus non-binding policy architectures and grandfathering versus per capita decision heuristics could be analyzed from a variety of theoretical and policy analytical perspectives. In the broader literature, these theoretical perspectives cut across environmental policy, ecological economics, climate science, environmental law, environmental psychology, political geography, political science, political ecology, political anthropology, international relations, and environmental sociology, which is by no means a comprehensive list. In this book, a multi-disciplinary and a meta-theoretical approach is deliberately adopted to present a multi-dimensional yet integrative critique of climate policy with a focus on meaningful policy and governance actions that must be taken in designing a post-Kyoto global climate governance and policy regime. From a meta-theoretical perspective, three theoretical perspectives are applied in this book to contrast and compare various elements of a post-Kyoto global climate governance regime: I characterize the first theoretical perspective as so-called “rational” perspective, primarily driven by game theoretical developments in computational sciences and international relations. Elinor Ostrom's (2005) Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework is a slight modification of this framework, from a rational to a boundedly rational direction. In this theoretical perspective, actors at multiple levels are represented as players with their strategic, tactical, and operational decision-making choices. Strictly speaking, rational players are ruthless and cold, who calculate their expected utilities for alternate decision-making choices under different information regimes. Since global climate change mitigation and adaptation policy issues are beset with risk and uncertainty, interactive decision-making by rational (and boundedly rational) actors could be modeled/explained under conditions of risk and uncertainty. This theoretical perspective seeks to elicit specific conditions under which international scale cooperation among different competitive players could/should emerge. Further, appropriate institutional designs that could/should emerge to solve environmental externality problems are explicitly derived through this theoretical framework.

I characterize a second theoretical perspective as “constructivist” and “social psychological.” Under this second perspective, game theoretical descriptions and/or prescriptions are assessed through critical policy analytical lenses that are used to analyze the complex challenge of designing an international post-Kyoto climate policy regime. In particular, these critical policy analytical lenses are labeled as the politics of scale; the politics of ideology; and the politics of knowledge. In the context of international climate policy, the politics of knowledge lens, for example, analyzes what type of knowledge “hegemonizes” the discourse for designing climate change mitigation and adaptation policies. In particular, politics of knowledge deeply affect the foundational policy and governance design questions concerning government, market, and society relationships. Marketization of climate governance can result in undermining governmental and societal goals through politics of knowledge. Further, knowledge “hegemony” can also influence the social construction of accountability and adaptation in global climate governance. Differential considerations of the knowledge could derive different conclusions about the design of policy mechanisms, binding versus non-binding emission reduction commitments and specific decision heuristics to allocate the emission entitlements. The politics of knowledge lens sheds light on such climate policy disputes and elucidates the politicized nature of climate science. In particular, the role of policy narratives and knowledge hegemony during international negotiations could be assessed through politics of knowledge policy analytical lenses.

Two connected aspects of hegemony in critical policy studies are emphasized:

On the one hand, hegemony is a kind of political practice that captures the making and breaking of political projects and discourse coalitions. But on the other hand it is also a form of rule or governance that speaks to the maintenance of the policies, practices and regimes that are formed by such forces.

(Howarth 2009: 301)

Both of these connected aspects of hegemony are explored in this book in the context of UNFCCC driven climate treaty negotiation process and politics of knowledge to set up and design a global climate governance regime. It is found in the negotiation data that hegemonic practices are utilized by high emitting countries through politics of knowledge in such a way that their proposed policy regimes are used to conceal the historical and future responsibility of high emitters and to naturalize their proposed policy architectures and decision heuristics. Using a critical policy analytical lens of politics of knowledge, this second theoretical perspective enables me to explain why high GHG emitting countries generally prefer non-binding emission reduction targets and grandfathering during the UNFCCC negotiations. Further, it enabled me to explore whether grandfathering and other types of non-binding post-Kyoto policy architectures are being naturalized in the international climate policy discourse to conceal the historical and future responsibility of high GHG emitters.

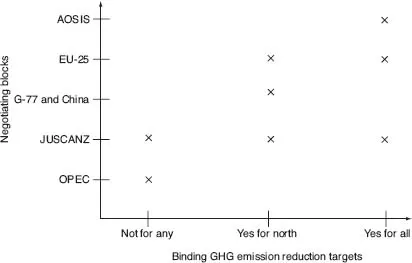

The notion of binding commitments has been strongly contested among various coalitions of countries in the UNFCCC negotiation process. Figure 1.1, as a demonstrative example, shows five negotiating blocks and their respective positions vis-à-vis binding versus non-binding GHG emission reduction commitments from a qualitative assessment of UNFCCC negotiation data from 1995 through 2010. The G-77 and China consistently negotiated for binding GHG commitments for industrialized countries. The group of Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), on the one hand, consistently opposed any binding GHG emission reduction commitments, while the group of Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), on the other hand, consistently supported binding GHG emission reduction commitments for all countries. European Union (EU)-15 countries and later EU-25 countries changed their positions from binding commitments for only industrialized countries to all the countries. The position of Japan, United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand (JUSCANZ) vacillated over the years from no binding commitments for any country to binding commitments for all countries to just the binding commitments for industrialized countries, as shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 The historical position of negotiating blocs in UNFCCC process vis-à-vis binding GHG emission reduction targets.

Notes

AOSIS: Alliance of Small Island States; EU-25: European Union; G-77 and China: group of about 139 developing countries; JUSCANZ: Japan, United States, Canada, Australia,and New Zealand; OPEC: members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries.

From rational game theoretical and boundedly rational institutional design perspectives (Luterbacher and Sprinz 2001; Cass 2006), it can be hypothesized that the coalitions that stand to lose most from binding commitments (e.g., OPEC and JUSCANZ) are opposed to any notion of binding commitments for emission reductions. On the other hand, the coalitions that stand to lose most from inaction (i.e., non-binding commitments), such as AOSIS, are in strong support of policy mechanisms that require binding commitments for a post-Kyoto Treaty.

In addition to binding versus non-binding emission reduction commitments, another important question in post-Kyoto climate policy discourse, especially multi level governance, concerns whether some universal decision heuristic must be necessarily used for a top-down allocation of emission entitlements or a bottom-up open-ended process be allowed to govern the emergence of binding or non-binding commitments at sub-or supra levels of nation states. Figure 1.2 shows twenty-two out of the sixty-four proposed post-Kyoto climate policy architectures categorized on the criteria of binding/non-binding emission reductions and top-down versus bottom-up policy development designs. Authors who primarily proposed these twenty-two policy architectures are mentioned in numerical order and relevant citations are shown at the bottom of Figure 1.2.

From a “constructivist” and social psychological perspective, It could be argued that the policy architectures that promote non-binding emission allowances, whether top-down or bottom-up, conceal avoidance of climate change problematic by naturalizing the discourse that nation-states may never be able to arrive at an effective and equitable international climate treaty. Some of these bottom-up and non-binding policy architectures shown in th...