- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Economic Survey

About this book

'A masterpiece of succinct analysis.'New Statesman

'Penetrating in analysis and closely packed in thought.'Financial Times

Analysing and examining the history of the economic events of the inter-war years, this book gives the reader both a sense of perspective of the larger scene of events on an international scale, whilst introducing facts and theories.

National policies of the UK, France, Germany, the USA, Japan and the former Soviet Union are discussed as are developments in international trade.

Information

PART I

THE CYCLE

CHAPTER II

1918–1925

CONDITIONS at the end of World War I were so much like those with which we have become familiar at the end of World War II that we need no detailed picture to bring them home to us. On the whole, they were not so bad as conditions in 1946, although of course to their contemporaries they seemed quite catastrophic. The French, for example, were appalled by the physical destruction in their country. They estimated that 2,700,000 people had been driven from their homes; that 285,000 houses had been destroyed and 411,000 houses damaged; that 22,000 factories, 4,800 kilometres of railways, 1,600 kilometres of canals, 59,000 kilometres of roads and 3,337,000 hectares of arable land had been rendered useless; and so on.1 But the world destruction done by the 1914 war was small compared with that done by the war of 1939; it was more or less confined to a gash five miles wide across France and Belgium, and it was made good with astonishing speed. There are closer parallels in other spheres. The collapse of Germany as an economic unit on this occasion compares with the collapse last time of Russia and of the Austro-Hungarian empire, with the hunger, exhaustion, bewilderment and economic and moral disintegration, which on both occasions made the organisation of relief measures so urgent a task. There was also, in the political arena, the same sense of hopelessness produced by the immediate outbreak of quarrelling and suspicion between the victors over the fate of the vanquished, with the additional complication last time that war continued in various parts of Europe for some years after the main conflict was over.

RELIEF

Then as now, relief seemed the most urgent task. In its later stages the Allied blockade had done its work well. By the end of 1918, and even before the end of the war, the peoples of Central Europe were starving, and agricultural output was so low that there was no prospect of their being able to feed themselves for a long time. Russia, also, was in an exhausted state owing to the civil war and the decline of production. The first task of the Allies was thus to bring food to the peoples of Europe, allied, neutral and ex-enemy.

The organisation and finance of relief is an important study, but one which we need not now pursue in detail.2 The work was done mostly by the American Relief Administration, which was created early in 1919 by the United States Government and which served also as the executive arm of the section of the Allied Supreme Council responsible for relief, until with the signing of the Peace Treaty in June 1919, the Council ceased to exist. Thereafter the American Relief Administration remained an official American body for some months, and then became unofficial. There were also many other private relief agencies in the field, but their work was overshadowed in volume by that of the A.R.A.

By June 1919, relief deliveries to Europe reached the sum of $1,214,000,000 and in the next four years a further $201,000,000 brought the grand total to $1,415,000,000. For most of this the receiving countries were expected to pay; 29 per cent was sold for cash, and 63 per cent on credit; only 8 per cent was given away.3

Magnificent work was done by the A.R.A., and without it the plight of Europe would have been beyond description. The fact that most of its deliveries were on a business footing—for cash or credit—proved of little consequence, as credits were freely granted, and, as things turned out, were mostly never repaid, being merged with war debts ten years later. A much graver deficiency was the fact that relief deliveries were confined to foodstuffs and excluded raw materials. Most of Europe was completely denuded of raw materials by the war, and economic life could not be reestablished until raw materials were made available to the factories. But the end of the war was followed by a boom, and an acute shortage of raw materials; in the ensuing scramble America, Great Britain and other countries with sound financial resources, got the lion’s share, and it was not until the slump that the countries of Central Europe were able to get the raw materials they needed to reconstruct their economies.

Raw materials was one of the problems discussed at the first post war International Conference (also the first League of Nations conference) held in Brussels in October 1920, when a scheme of international credits was agreed; but by this time the boom was over, and the Ter Meulen plan (as it was called after its proposer) was never actually brought into effect. It was this difficulty over raw materials which caused the relief organisation of our times, the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration to be instructed not to confine itself to food, but to give equal priority to the materials needed for reconstruction.

BOOM AND SLUMP

In Western Europe and the United States there was no such acute distress as in Central Europe. Here the problem was simply that of reconversion from war to peace. Millions of men were anxious to be released from military forces, and to be reabsorbed into industry; and factories which had been engaged on munitions had to be converted to civilian needs. As the war neared its end considerable apprehension had been felt lest the process of reconversion should prove prolonged and painful. Many persons expected that the curtailment of war demands would produce a slump, and in this context there was considerable discussion of the future of wartime controls. For in the first world war, as in the second, a whole network of controls had been built up and in a number of industries, e.g. railway transport, coal and munitions in Great Britain, the Government itself was actively engaged.

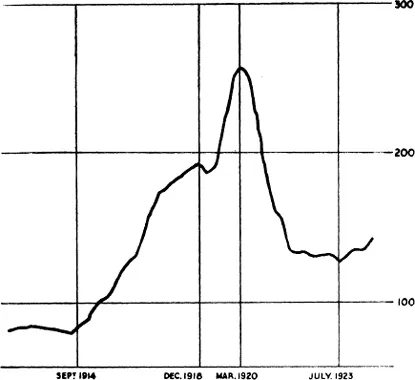

Fears of a slump proved to be unfounded. For a month or two after the Armistice there was uncertainty, and a slight recession, but by March 1919 this gave way to a boom of astonishing dimensions. In Great Britain prices had risen during the war at a more or less even rate; as Chart I shows, they shot up in the next few months to heights which would not have been thought possible. This was unfortunate in many ways; but the favourable effect of the boom was to simplify immensely the switch over from war to peace. Factories were deluged with orders, and in turn absorbed labour rapidly. Demobilisation was thus speeded up; within five months of the Armistice Britain had demobilised two million men; four million were out by the end of the year, and there was virtually full employment. The experience of the U.S.A. was similar. Both countries also, in this atmosphere, grew impatient of restraints. Business men demanded the end of controls, and the process of decontrol was greatly accelerated.

CHART I. WHOLESALE PRICES IN THE U.K., 1912–1923.

The main cause of the boom seems to have been a universal desire to replenish stocks. All over the world larders, wardrobes, and shops were empty; all over the world, too, purchasing power had accumulated. The rush to replenish drove prices up. Moreover, additional purchasing power continued to be created, as Governments were still maintaining expenditure at high levels, retaining wartime practices of deficit budgeting. Governments were also anxious to keep interest rates low so that short term debts could be converted to long on favourable terms. The boom collapsed when raw materials and foodstuffs, which had accumulated overseas during the war for lack of shipping, began to arrive in Europe; when factories began to meet the accumulated demand; and when financial authorities, desiring to check the speculative inflation, took steps to restrict credit. Prices began to fall in March 1920, and within the next two years, were halved.4 The year 1921 was thus a bitter year for the world. The boom had raised hopes that the problems of reconstruction could be minimised by a high level of economic activity. But instead, with the slump, men were standing idle in millions, industrial unrest was high, and the future was black and uncertain. The magnitude of the task still to be accomplished was obvious.

EASTERN EUROPE

One of the areas of greatest dislocation was Eastern Europe, whose countries had failed to get securely on their feet again. Several new countries had come into existence. The old Austro-Hungarian Empire had been torn asunder; three new countries, Austria, Czechoslovakia and Hungary had been formed out of it, and parts of its territories had been added to neighbouring states. The peoples of Eastern Europe were hungry, and physically and spiritually exhausted. The railway system was in a sad state of disrepair, as Table I shows.5

TABLE I

PERCENTAGE OF RAILWAY ROLLING STOCK FIT FOR SERVICE AT THE BEGINNING OF 1926

Country | Locomotives | Wagons |

Austria | 63 | 67 |

Baltic Countries | “situation chaotic” | |

Bulgaria | 37 | 56 |

Czechoslovakia | 62 | 88 |

Greece | 76 | 86 |

Hungary | 27 | 76 |

Poland | 70 | 90 |

Roumania | 29 | 57 |

Russia | 15 | 20 |

Governments and administrative systems were in chaos, having in many cases to be created virtually from nothing.

To all this was added the consequences of a fierce nationalism. Austria and Hungary were disliked by the peoples liberated from their rule, and these peoples set out to make their economies as independent of these two countries as they could. New currencies were adopted to replace the Austrian crown. The Austro-Hungarian railway system was disintegrated; each country seized the fixed equipment and rolling stock within its borders, and as for some time no country was willing to allow rolling stock to cross its border, fearing that it would be seized, goods had to be unloaded and reloaded at frontier stations, this adding greatly to cost and inconvenience. In any case, for some time, trade was virtually prohibited. In each country imports and exports were prohibited except under licence, and as food and raw materials were so scarce, very little was allowed to cross frontiers until the boom was over.

The Austro-Hungarian empire had been a single economic unit covering a large free trade area. Now it was split into a number of countries each with its own currency and tariffs. The railways had been constructed with Vienna and Budapest as centres. Now each country remodelled its communications, to turn upon its own capital. Industries in one part depended on raw materials from another. Now the raw materials were kept, and efforts made to foster local industries, while men and materials stood idle in what was now a different country. For example, “Austria was left with sufficient spinning mills and finishing works, but with too few looms. At the same time Czechoslovakia, where the weaving mills were located, gave protection to an infant spinning industry, and so cut off the natural outlet for Austrian yarn. Austria’s famous tanneries lost their sources of skins and tanning materials; her Alpine iron works lost their coal—about half of the old coal fields having gone to Czechoslovakia and Poland. Czechoslovakia contained a high proportion of the old Austrian industries, but n...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- CONTENTS

- PREFACE

- I. Introduction

- PART I. THE CYCLE

- PART II. NATIONAL POLICIES

- PART III. TRENDS

- Statistical Appendix

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Authors Cited

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Economic Survey by W. Arthur Lewis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.