1 Energy accounting

Sources of ambiguity

The roots of virtually any problem with energy accounting lead back to the inher-ent ambiguity of the very concept of energy itself (section 1.1, below). So to start, we analyze three epistemological sources of ambiguity that must be acknowl-edged by those willing to account quantities of ‘energy’. First of all, we address the lessons from hierarchy theory telling us that the quantification of the generic concept of ‘energy’ requires us to consider and represent energy transformation one scale at a time (section 1.2, page 15). Then we get to the lessons from classic thermodynamics telling us that different energy forms – e.g. thermal energy and mechanical energy – do have different qualities, and therefore cannot be aggre-gated in a substantive way (section 1.3, page 18). Finally, the development of non-equilibrium thermodynamics (required when dealing with living and self-organizing systems) implies an additional semantic ambiguity associated with the fact that metabolic systems, according to their own identity, define locally for themselves what is useful (negentropy) or waste (entropy) (section 1.4, page 21).

1.1 The inherent ambiguity of the concept of energy

Consider the simple question: What is energy? It is not easy to provide a defini-tive, simple, and crisp answer within the traditional scientific approach of reductionism. Clicking the button ‘what is energy?’ of the website of the US Energy Information Administration (EIA, 2012), we find an explanation organ-ized in three parts.

First, we find the classic ‘scientific’ definition typically found in textbooks:

Energy is the ability to do work.

Second, we are presented with a list of different forms of energy:

(i) Heat (thermal); (ii) Light (radiant); (iii) Motion (kinetic); (iv) Electrical; (v) Chemical; (vi) Nuclear; (vi) Gravitational.

And finally, we get a semantic explanation:

Energy is in everything. We use energy for everything we do, from making a jump shot to baking cookies to sending astronauts into space. There are two types of energy:

- • Stored (potential) energy

- • Working (kinetic) energy

For example, the food you eat contains chemical energy, and your body stores this energy until you use it when you work or play.

This elaborate explanation conveys the impression that the concept of energy can only be understood by integrating several distinct narratives and semantic refer-ents, which are difficult to integrate into a concise and coherent formalization. Indeed, the ambiguity of the definition given by EIA is not due to a lack of expert-ise of those who prepared the website, but rather to the very nature of the concept of energy.

Yet, the general perception of lay people is that the concept of energy is the ultimate source of rigor and precision typical of physics, the queen of hard sciences. Nothing is farther from the truth. Energy is essentially a semantically open concept used by the human mind to study and explore the external world, and for this reason it is a concept that has successfully resisted numerous attempts of substantive definition and quantification. As Feynman, a Nobel laureate in physics, pointed out:

... it is important to realize that in physics today, we have no knowledge of what energy is... it is an abstract thing in that it does not tell us the mecha-nism or the reasons for the various formulas

(Feynman et al., 1963, Chapter 4, p. 2).

One of the pioneers of energetics, Rankine, in his ‘Outlines of the Science of Energetics’, provides a generic definition of energy, ‘the capacity to effect changes’ (Rankine, 1855, p. 385). The broadness of the definition has not changed with time: ‘energy is an abstraction, designed to account for the outstanding differences between the initial and final state of a system to which some change has occurred’ (Crane, 2003). When providing a definition of energy, it is simply necessary to remain generic in order to avoid getting into specific context and space-time scale dependent settings. Note that the standard textbook definition of energy provided by the EIA, ‘the potential to do work’, in reality refers to the concept of ‘free energy’ or ‘exergy’. This is a potential source of confusion that will be discussed further on. A drawback of the-potential-to-do-work definition is that it is an impredicative or context-dependent definition in its nature (see Box 1.1, page 14). We must first define ‘work’ in order to be able to identify and meas-ure ‘energy’, but this solution does not solve our original problems, since the definition of ‘work’ is as elusive as that of energy.

Box 1.1 The distinction between predicative and impredicative definitions

In natural language it is well known that certain words such as ‘right’, ‘left’, ‘before’ or ‘after’ must rely on an external referent in order to convey mean-ing. Hence the meaning of these words depends on the context in which they are being used. Such words are called deictic and they require contex-tual information to be effective.

The concept of impredicativity is quite similar. We face an impredicative definition when a property is possessed by an object whose very definition depends on that property. The concept is therefore associated with the exis-tence of a process that generates the definition of itself and its parts in a circular way.

A simple example of this concept is: how to define if one is ‘tall’? A predicative definition would be: ‘if a person’s height is more than 183 cm (6 feet), then she/he is tall’. Having measured a person, we can define with-out ambiguity whether she/he is tall or not. On the other hand, an impredicative definition of being tall would be: ‘if the person’s height is greater than that of 75 per cent of the other persons in the group, then she/he is tall’. The outcome of this definition depends on the circumstances. For example a person of 183cm (‘tall’ in the predicative definition) may be defined ‘short’ when considered as a member of a professional basketball team.

The predicative definition is useful only if we have prior knowledge (agreement) about the associative context in which the assessment will be used. The impredicative definition, on the other hand, is not substantive but much more flexible when one has to deal with different situations and contexts.

The confusion in the use and quantification of the term ‘energy’ is augmented by the fact that this term is not only used in many different scientific contexts and narratives, but also in everyday language. Indeed, the everyday use of the term ‘energy’ and its related terms, effort and power, is extremely common and the associated semantic message is intuitive and easily grasped: ‘she is an energetic teacher’, ‘I no longer have the energy for doing this’, ‘this will require a lot of effort’, ‘she is a very powerful person’. It is probably precisely because of this familiarity that we encounter an extreme difficulty in understanding and in prop-erly using the various non-equivalent formalizations of these concepts when using scientific narratives.

As mentioned, in the fields of physics and engineering, use of the term energy is based on the classic impredicative definition, ‘the potential to do work’. This entails shifting the problem from defining ‘energy’ to defining the term ‘work’, which is anything but easy. Certainly, work can be quantified in the ideal world of elementary mechanics using the standard definition: ‘work is performed only when a force is exerted on a body while the body moves at the same time in such a way that the force has a component in the direction of the motion’. Work can also be quantified in terms of classic thermodynamics, after establishing equiva-lence between ‘heat’ and ‘work’: ‘the work performed by a system during a cyclic transformation is equal to the heat absorbed by the system’. In this case, using a calorimetric equivalence, assessments of both work and energy are expressed in the same unit of measurement, joules (J). However, the elaborate description of work in elementary mechanics and the calorimetric equivalence derived from classic thermodynamics are of little use to characterize work in real-life situations.

In fact, in order to characterize the performance of various typologies of work we need qualitative characteristics that are very often impossible to quantify in terms of either mechanical work or heat equivalence (Giampietro and Mayumi, 2004). For example, the work of a director of an orchestra cannot be described using the above definition of elementary mechanics nor can it be measured in terms of heat. A sole accounting of the mechanical work involved would not distinguish between a famous director and an ordinary policeman regulating traf-fic. Similarly, measuring the joules of heat sweated by the director during the concert will not tell anything about the quality of his performance. ‘Sweating’ and ‘quality of directing’ simply do not map very well onto each other. Indeed, it is virtually impossible to provide a physical formula or general model quantifying in substantive terms the quality (or value for society) of a given work. What has been achieved after fulfilling a useful task is not directly related to a quantitative accounting of how much energy input has been consumed.

The field of economics also employs the term ‘energy’. Given its relevance as a key commodity in modern economies, economists are increasingly interested in the analysis of energy flows. Energy inputs are, in fact, strategically important commodities for the successful operation of modern economies. This economic interest has led to the adoption of a new category of energy accounting, ‘energy commodities’, which is used, not without controversy, in the energy statistics of Eurostat and the International Energy Agency.

1.2 The lessons of hierarchy theory

Starting from the premise that energy is an elusive concept, any attempt of energy accounting cannot but be a heroic effort. Physicists and engineers have mastered how to quantify energy transformations. However, they can do so only when adopting one scale at a time. The epistemological challenge faced when trying to analyze a system using simultaneously different scales is the subject of the field of hierarchy theory (Simon, 1962; Koestler, 1968, 1969, 1978; Whyte et al., 1969; Pattee, 1973; Allen and Starr, 1982; Salthe, 1985; O’Neill et al., 1986; O’Neill, 1989; Allen and Hoekstra, 1992; Ahl and Allen, 1996; Giampietro, 2003). In brief, hierarchy theory can be defined as ‘a theory of the observer’s role in any formal study of complex systems’ (Ahl and Allen, 1996, p. 29). It explic- itly acknowledges the unavoidable existence of multiple, non-equivalent identi-ties for the same system when it is observed at different scales. So the observer, deciding how to observe a complex system, defines, with the choices made in the pre-analytical phase, what will be the result of that observation. Clearly, what is observed is still the complex system, but the observer can choose, when selecting the scale and the associated descriptive domain, one particular view or aspect of it at the time. As a matter of fact, the idea of a system having multiple identities when observed at different scales provides the definition of a hierarchical system:

- • ‘a dissipative system is hierarchical when it operates on multiple space-time scales – that is when different process rates are found in the system’ (O’Neill,1989);

- • ‘systems are hierarchical when they are analyzable into successive sets of subsystems’ (Simon, 1962, p. 468);

- • ‘a system is hierarchical when alternative methods of description exist for the same system’ (Whyte et al., 1969).

In the jargon of hierarchy theory, different forms of energy described on different scales can only be quantified by adopting non-equivalent descriptive domains. The concept of a non-equivalent descriptive domain was first introduced by Robert Rosen (1985, 2000) to indicate a situation in which two quantitative assessments cannot be reduced to each other within a single formal model (see also Giampietro et al., 2006). In the jargon of physics this situation is described as the existence of incoherent quantitative descriptions.

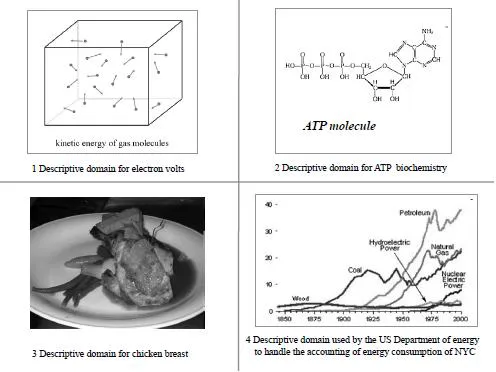

A few examples of non-equivalent representations of energy forms are provided in Figure 1.1 (page 17). They specifically refer to the following non-reducible quantitative energy assessments:

- • The assessment used to describe and measure quantities of energy associated with the behaviour of tiny particles, based on the electronvolt (eV), a unit of energy equal to approximately 1.602X10–19 J. Just to give an idea, the energy of a molecule of oxygen moving in the air we breathe is 0.03 eV.

- • The assessment used to describe and measure the quantities of energy asso-ciated with cellular processes in the fields of biochemistry and physiology is based on ATP. ATP is an energy rich molecule used in biochemical processes; it is the biochemical fuel of living systems. The energy equivalent of ATP has been estimated at 58 J/g of ATP associated with 3,600 turnovers/day of 50g p.c. (http://trueorigin.org/atp.asp).

- • The assessment used to describe and measure our food energy intake refers to the scale of the human body. For instance, 100g of chicken breast provides150 kcal or 630 kJ of food energy to the human body.

- • The quantitative assessment used to describe the metabolism of a social system – the different primary energy sources required to carry out a given set of societal functions – is usually expressed in tons of oil equivalent (TOE). For example, we may want to assess the energy used by New York

City and will find that this is a mix of flows of different energy forms includ-ing petroleum, natural gas, coal, wood, and electricity generated in different ways (e.g. nuclear, hydroelectric).

Figure 1.1 Quantitative assessments referring to energy forms observable only at different scales

Photo source: Wikicommon.

It is unrealistic to expect that a single method of accounting could exist to effectively handle the heterogeneous information space described by these four assessments covering a range of order of magnitude from 10–19 joules to 1012 joules. The fact that all of these forms of energy can be expressed in joules should not be taken as a sign that it is possible to reduce the relative quantitative assess-ments into a single number, by using a single comprehensive model. The information required for such accounting is based on different typologies of descriptions of networks of transformations which are in turn referring to differ-ent scales.

When trying to aggregate data referring to ‘energy quantities’ defined on non-equivalent descriptive domains (different scales), analysts are forced to use quantitative assessments that can only be obtained from non-equivalent measure-ment schemes. The problem is generated by the fact that these different measurement schemes deal with different typologies of energy transformations taking place at different scales.

In general terms we can say that data generated within non-equivalent obser-vation processes cannot be summed even if they are expressed in the same unit. In fact, the relative measurement schemes do entail different types of error bars determined by the differences in scale. Funtowicz and Ravetz (1990) illustrated this point with the following joke. There is a skeleton of a dinosaur in a museum with the original inscription in the label reading: ‘age 250,000,000 years’. However, the janitor of the museum has corrected the inscription into ‘age 250,000,008 years’. When asked about the correction, the janitor replied: ‘When I got this job, eight years ago, the age of this dinosaur was 250,000,000 years. So, I am just keeping the label of the age accurate.’

As noted by Funtowicz and Ravetz (1990), there are no written rules in math-ematics that prevent the summing of two addends expressed in the same unit. Therefore the sum of 250,000,000 years and 8 years is admissible according to formal rules. Nevertheless, the explanation given by the janitor simply does not make sense to anybody familiar with measurements, and this is the pun of the joke. The measurement scheme used to provide an assessment of hundreds of millions of years is incompatible with that used for individual years because of the too large a difference in the associated error bars. For this reason, the ‘accu-rate’ assessment of 250,000,008...