eBook - ePub

Primary School English-Language Education in Asia

From Policy to Practice

- 152 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Primary School English-Language Education in Asia

From Policy to Practice

About this book

In Asia, English is no longer a foreign language but a key resource for education, government, business and the general public. Whereas thirty years ago, British and American experts believed that the best way to improve the quality of English teaching was to cancel any programs below the secondary level, Asian nations as well as European are now introducing English in primary school. But there are major obstacles to overcome: the training of enough local teachers or the hiring of English speakers, the preparation of suitable teaching materials, the development of useful tests, and the design of workable curriculums. The chapters in this book, written by leading English-teaching professionals in seven Asian countries and originally delivered at the 2010 annual conference of Asia TEFL which took place in Hanoi, Vietnam, describe and analyze national policies and how they are implemented. The coverage is wide: China with its huge number of students learning English, Japan working to make the transition from elementary to secondary school seamless, Singapore continuing to use English as medium of instruction for its multilingual population, Korea developing English education policies to recognize the increased role of English alongside the national language, India building on its colonial past to make English an economic resource, Vietnam fitting English into a program of national rebuilding, and Taiwan spreading its English teaching outside the national capital. This is not a report of the views of outside experts, but of local experiences understood by local scholars of international standing. Policy makers, educators, researchers and scholars will be able to gain valuable insights from Asian experts.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Primary School English-Language Education in Asia by Bernard Spolsky,Young-in Moon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Primary English Education in China

Review and Reflection

Xin Wu

INTRODUCTION

In the year 2001, English started to be a required subject in the new curriculum of China’s primary schools (MOE, 2001a). By the year 2008, English was being taught as a subject in an average of 60% to 70% of primary schools, and in several large and mid-sized cities, 100% (Wang, 2008). However, the debate over the necessity and feasibility of teaching English in Chinese primary schools still continues: on the one hand, having an English curriculum for primary schools is being promoted as one of the key missions of the educational reform started at the beginning of the 21st century (Chen, 2008; Wang, 2011); on the other hand, discussions involving schools, teachers and researchers indicate the teaching of English in primary schools is facing some problems and difficulties (Bao, 2004; Cui, 2004; Fan, 2007; Feng, 2011; Liu, 2001; Wu, 2011; Wu & Yang, 2008; Zou, 2011).

In order to obtain a clear picture of primary English education in China and to explore and understand the present situation, this paper will present research gathered from issued government documents, reports from schools and data collected in surveys. The author will take a close look at the development of English teaching in primary schools in China, the implementation of policies at different stages and the problems as well as the achievements in English teaching in Chinese primary schools.

One phrase that needs to be defined is the term “primary schools”: in this paper, “primary schools” indicates “compulsory” full-time primary schools whose target students are ordinary children of school age (aged 6 to 12 years). The other types of schools that are not included in this research are called “foreign language schools” and “foreign language training schools”, in which students are required to have a much higher proficiency in foreign languages.

HISTORY OF PRIMARY ENGLISH EDUCATION IN CHINA

Primary English Education before 1978

In reviewing the literature related to Chinese curricula and syllabi, the author found that primary English education was officially mentioned in the years 1912, 1915, 1916 and 1962 (CMRI, 2001). However, in practice, English was never officially taught in the wide range of primary schools. The main problem for primary English education during this period lay in the lack of a well-organized curriculum. For instance, an official document in 1962 (CMRI, 2001a) clearly suggested that primary school students should begin studying Russian or English in Year 4 and Year 5. It also suggested that the teachers of foreign language teachers should have adequate language proficiency and good pronunciation. It stressed as well the need for continuity in studying the same language after entering middle school. However, the author found no textbooks specially developed for primary English during this time; if there were any, they were used only in a limited area. Instead, it was generally recommended that primary schools use the first two books being used for middle schools (CMRI, 2001a, p.103). Therefore, in practice, English was not actually taught in ordinary primary schools in China before 1978. If there were any, the number of schools was extremely small.

Primary English Education from 1978 to 2001

In 1978, China started to try out a new approach in many areas; in education, the school curriculum was required to include English in primary school. The syllabus in 1978 covered both primary school English and middle school English, clearly stating the goals and requirements, the content and class hours for the different stages in all schools. The syllabus stated, “teaching English from Year 3 [is required] in primary schools” (CMRI, 2001b, p. 120); the required class hours were 152 teaching hours for Year 3, 136 hours for Year 4 and 136 hours for Year 5.

In 1979, a special document was again issued by the Ministry of Education (henceforth the MOE), emphasizing that English should be one of the foreign languages taught in primary and middle schools (CRMI, 2001c). It declared, for the first time since 1949, that English had an important position in the curriculum and that primary English should be taught gradually in key schools and schools in developed cities.

In 1980, the MOE issued a national syllabus for schools (CMRI, 2001d). In this document, there were two curricula designed for English study: one was designed to teach English beginning from Year 3 in primary schools and the other from Year 1 in middle schools. What made the syllabus for primary schools so important was that it stressed again in detail the teaching requirements for pronunciation, grammar and vocabulary from Year 3 to Year 5 in primary schools.

The two above syllabi, that is, the syllabus in 1978 and the one in 1980, were not fully implemented in actual practice due to a tremendous gap between the requirements and the reality in schools. In May, 1982, a national meeting on foreign language teaching was held; after the meeting, in July, 1982, the MOE issued a document (CMRI, 2001e) stressing the importance of teaching of foreign languages in China. However, apart from further stimulating educators to improve the quality of English teaching in schools, it clarified the year in which English language study should start, stating that “English should be studied generally from Year 1 in junior middle schools. If there is a lack of English teachers in some areas, English can be studied from Year 1 in senior middle school” (CMRI, 2001e, p.157). The development of primary school English, therefore, stood still for a short period. One of the main reasons for this postponement was, as it said, “the low proficiency of [existing] teachers and the great lack of teachers” (CMRI, 2001e, p. 157).

However, from the late 1980s until the year 2000, primary English education in China developed rapidly due to the need for higher language profi- ciency in developed areas and English was included in the local curriculum of some primary schools. In order to meet the needs of primary English education, the People’s Education Press (henceforth PEP), the national publisher of school textbooks, even issued a guideline in 1991 for the writing of primary English textbooks (Liu, 2008) and started to write and provide primary English textbooks for schools in most areas where English was taught at that time. By the end of the 20th century, “about 30 provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions had started to teach English in primary school” (Liu, 2008, p. 22) and by the year 2001, the number of primary school students studying English was over 10 million (Li, 2001). The number was not very impressive compared with the total number of 125 primary students in 2001 (MOE, 2002), but it was a good indication of the growing English language movement in China’s primary schools.

Primary English Education since the Curriculum Reform of 2001

After entering the new century, China started a reform in education, and primary English became one of the important targets in this reform. A document issued in early 2001 (MOE, 2001a) officially endorsed the teaching of English in primary schools all over China, stating that, from the autumn of 2001, English should gradually be introduced into primary school in cities and counties all over the country, and from the autumn of 2002, English should gradually be included in primary schools in towns and rural areas. This document clearly stated the starting year to be Year 3, but allowing different areas to have their own targets and stages according to their own unique situations. Along with this document, a description of the basic requirements for primary English was issued as well (MOE, 2001a), a clear indication that English had officially been brought back to classrooms in primary schools.

In 2001, the MOE issued “National English Curriculum Standards for Compulsory and Senior High Schools (Experimental Version)” (henceforth NECS) (MOE, 2001b). The standard defined the target of English language teaching in school as the development of students’ integrated competence.

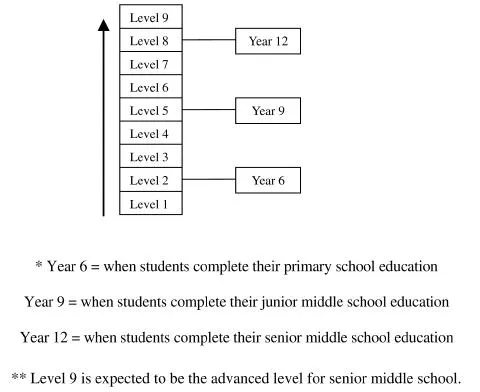

Figure 1.1 Levels of requirement in NECS (adapted from MOE, 2001b).

It believed that the building of such competence depended on the overall development of students’ language skills, language knowledge, emotional development, learning strategies and awareness of other cultures. The key feature of NECS was the division of students’ language competence into nine levels. Level 1 and Level 2 are the target requirements for primary English, as illustrated below (Figure 1.1).

According to NECS, the nine levels function as suggested targets for student achievement. For example, if English is taught from Year 3, the requirement of Level 1 should be the target for Year 4 and Level 2 for Year 6. However, if schools in some areas cannot manage to teach English in primary, the requirements at Level 1 and Level 2 should not be the targets for students in those areas. On the other hand, if some primary schools start to teach English in Year 1, the requirements for students in this area can be above Level 2 by Year 6.

The flexible requirements for primary English education lie in one of the principles of the educational reform begun in 2000 (i.e., the new curriculum has, in terms of administration, three levels of management). The first management level is the national curriculum in which the core courses have the same requirement nationally in terms of targets, class hours, assessment and so on. The second level is the local curriculum in which the local educational administration can arrange the curriculum according to local needs. The third management level is the school curriculum where schools can make their own decisions on what extra content they wish to add. In the present school reform, primary English in the current curriculum has gained one “privilege,” that is, English is not required to be tested officially, though English is undoubtedly one of the courses officially required in the national curriculum.

In summary, in examining the history of primary English education in China, the author found that English has been taught in primary schools in developed areas in China for quite a long time and, at present, has become a national required subject in schools. However, the author also found that there is a lack of understanding as to how to teach English in all primary schools under a well-designed system and that a lack of sound experience in teaching English to young learners in such a vast country as China is a problem. Therefore, it was to be expected that arguments and debates on whether, when and how English should be taught in all primary schools would start at the beginning of the latest educational reform and continue up to the present day (Bao, 2004; Cui, 2004; Fan, 2007; Feng, 2011; Wang, 2011; Zou, 2011).

PRIMARY ENGLISH EDUCATION: CURRENT PRACTICE

The history of English teaching in China’s primary schools presents the question of how the top-down decision could be implemented in practice under such a difficult situation. The research showed that the arguments and debates did not deny the importance of teaching and learning English but rather raised doubt as to when and how English should be taught in primary schools. To avoid falling into a similar debate, this author stepped back and looked for information on several aspects of how primary English education is actually carried out in schools at three levels. At the school level, the curriculum goals and teaching materials will be discussed. At the classroom level, the teaching hours, student numbers and teaching methods will be presented, and the last level will deal with teacher qualifications and teacher training.

In addition to the data and information published by other researchers, information employed in this study has also been taken from two surveys in which the author was involved from 2005 to 2009.

Survey I (2005–2006), supported by the MOE, involved 11 provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions. The 11 areas were selected based on the development status of the target areas, which were divided into highly developed areas, developed areas and less developed areas. Based on this concept, a similar division was followed in the cities, in the counties and towns, and with individual teachers. Altogether 18,519 questionnaires were collected, 101 lessons were observed, and 89 interviews were conducted (Wu & Yang, 2008). The initial target of this survey was to obtain information about the current English teachers in both primary schools and middle schools, but in this paper, only information concerning primary English has been considered.

Survey II (2007–2009) was part of a research project funded by the National 11th Five-Year Plan. This survey involved 1099 primary English teachers from six selected provinces (including Qinghai, Yunnan, Hubei, Fujian, Shandong and Zhejiang). The purpose of this survey was to find out how English was taught in primary schools and the feasibility of using the current textbooks. Information was collected through questionnaires, classroom observation and interviews with teachers and stu...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Routledge Critical Studies in Asian Education

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures, Illustrations and Photos

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 Primary English Education in China: Review and Reflection

- 2 Issues in the Transition of English Education from Elementary Schools to Secondary Schools

- 3 Language Teaching Methods in Singapore Primary Schools: An Historical Overview

- 4 Primary School English Education in Korea: From Policy to Practice

- 5 Young Learner English Language Policy and Implementation: A View from India

- 6 Teacher Preparation for Primary School English Education: A Case of Vietnam

- 7 Planning and Implementation of Elementary School English Education in Taiwan

- Contributors

- Index