- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Originally published in 1987, Out of the Cage brings vividly to life the experiences of working women from all social groups in the two World Wars.

Telling a fascinating story, the authors emphasise what the women themselves have had to say, in diaries, memoirs, letters and recorded interviews about the call up, their personal reactions to war, their feelings about pay and the company at work, the effects of war on their health, their relations with men and their home lives; they speak too about how demobilisation affected them, and how they spent the years between two World Wars.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Out of the Cage by Gail Braybon,Penny Summerfield in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 20th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

This book is about women's experiences in the First and Second World Wars.1 In it we are aiming to do two things. The first is to make the voices of working women, of whatever class, heard. Women have had much to say about their lives when asked, and the rise of oral history has led to a growing number of fascinating collections of wartime memories in the past few years. As we wrote, we allowed the concerns of the women themselves to influence the form of the book. So we have written about the experience of call up, personal reactions to war, feelings about the pay and the company at work, and the effects of war on women's health and home lives. Women's pride in their work comes through very strongly in their testimony and so too does the sense of freedom many felt when comparing their war work with the confines of home or a typical ‘woman's’ job. In both wars there were women who felt that they had been ‘let out of the cage’ even when they were critical of the pay and conditions they had to put up with, and the way that men reacted to them.

The second thing we aim to do is to lay bare the prejudices surrounding women, and show the way in which attitudes towards their roles at home and at work remained remarkably consistent over nearly fifty years. Both wars put conventional views about sex roles under strain. Women were after all working long hours next to men, learning new jobs, and earning better wages than they had before. They were, particularly in the 1939–45 conflict, partners with men in the war effort. Commentators during the First World War feared that women would not want to settle down to being the nation's wives and mothers after the war and expected changes in the relations between the sexes to result from their new work. But the surprise and hostility with which women were greeted when they were once again moved on to new jobs in 1939–45 do not suggest that the First World War had led to permanent changes. And although a larger number of older and married women went out to work during and after the Second World War they were not considered to be as important and valuable as male workers. Nor was there any suggestion that they should stop being primarily responsible for home life. The belief that men and women naturally occupy separate spheres within which they pursue quite different tasks was not shaken during either war: men were not expected to take an equal share of domestic responsibilities; nor was it considered proper that women, like men, should die for their country.

The book is divided into two sections on the respective wars. Although we cover similar themes in each, the two halves of the book are not perfect mirror-images of each other. As individual authors (Gail writing about the First World War and Penny about the Second), we each have our own style, and our own ways of putting things. Had we tried to obliterate these differences we would have made life harder for ourselves, and would probably have produced a less interesting book for the reader! However, other things also affected the way we wrote the two halves of the book, and we need to make these clear.

The wars themselves were quite dissimilar. The fact that they are known as the First and Second World Wars encourages people to see them as alike. But apart from the fact that in each case the main enemy was Germany and the allies were France, the USA and Russia, there were really very few similarities between them. The casualty figures for each war are revealing. In 1914 the population of England, Scotland and Wales was around 37 million. In the following four years 744,000 men in the armed forces and 14,661 men in the Merchant Navy were killed, and 1,117 civilians died in air raids. (Influenza accounted for another astonishing 150,000 deaths in 1918–19.) In 1939 the population was around 40 million. Between 1939 and 1945 closer to one quarter rather than three quarters of a million were slaughtered (264,443), but in addition this time 624 servicewomen were killed. Twice as many merchant seamen met their deaths in the vicious submarine warfare of the Atlantic and British coastal waters (30,248). Far more civilians were killed in air raids (60,595) and almost as many women as men died as a result of bombing.2

In the First World War British action was concentrated in Flanders on the ‘Western Front’ and civilians were relatively safe. The Second World War was more truly a ‘world’ war. Between 1939 and 1945 there were ‘theatres of war’ in Europe, the Atlantic, the Mediterranean, North Africa, the Middle East. After Japan entered the war as an ‘Axis’ ally of Germany and Italy at the end of 1941, there were fronts in the Far East, the Pacific and Burma as well. But though war service took many servicemen and women far from home, successive waves of bombing also brought the danger, fear and tragedy of war to the heart of the civilian population.

In military terms the wars were quite different. The stagnation of trench warfare characterised the First War, whereas the mobility of fighter and bomber planes, fast-moving tanks, warships and submarines was a key feature of the Second. This mobility gave rise to the situation, quite unknown before, where men were fighting for their lives in aeroplanes over the channel by day and then drinking in the village pub near the air base in the evening. Camps and barracks all over Britain were bursting with servicemen and women, especially once American GIs started to arrive in 1942. The presence of so many people in uniform in British towns and villages during the Second World War, compared with their ‘invisibility’ in Flanders in the First, affected the ways civilians and troops reacted during the two conflicts. Even though some members of the armed forces were posted abroad or captured and held as prisoners of war and did not return home for as long as six years in the Second World War, the division between the home front and the war front was nothing like as stark as it had been in the First.

In spite of the build-up of the British Fleet, and talk of hostilities with Germany, the war in 1914 came as a complete surprise to most people in Britain. When war was actually declared, many were gripped by patriotic fervour. They assumed that this would be a minor skirmish in Europe in which the British would sort out the Germans, after which life would rapidly return to normal. As the months of fighting stretched to years, and the death toll reached appalling heights, enthusiasm waned considerably, even though there always remained a gulf between the fighting men, who experienced the grim conditions of trench warfare and the people at home who carried on with lives that were almost normal. Eventually people simply longed for the war to be over. It became increasingly difficult to hold on to what it was supposed to be about, and discontent was fuelled by the government's industrial policy and its failure to act effectively on such matters as inadequate housing, high rents and food shortages. The experiences of 1914–18 left many with a lasting horror of the whole idea of war, and a determination that there should never again be such a dreadful conflict.

In contrast with the jingoism of 1914 most people were not enthusiastic about going to war in 1939. The fight was seen as something which had to be undertaken, in spite of the strong peace movement of the 1930s. Even though anti-German feeling was whipped up in the press and by politicians, the enemy this time was not such much a nation as a political system headed by a man who would clearly stop at nothing in his pursuit of establishing a ‘Greater Germany’ and might very well invade Britain. When they went to war this time, the British people knew that they were defending themselves against Hitler and Nazism. The confusion shown by one new recruit in 1914 who told his companions, ‘I'm a-goin’ ter fight the bloody Belgiums, that's where I'm a-goin’,’3 was unimaginable in 1939. The disillusionment which grew during 1917–18 was not repeated in 1944–5. The mounting number of civilian deaths made people all the more desperate not to lose the war, and politicians’ promises of rewards for wartime sacrifices increased determination to create in the aftermath of war a more equitable Britain, in which there really would be homes for heroes, with in addition full employment, free health care and a system of state welfare ‘from the cradle to the grave’.

As far as women were concerned, the wars were also different in a number of ways. In both, Britain was beleaguered by the submarine blockade which led to shortages of all sorts of essentials from food to soap and clothing. But the interruption to trade was far more serious in the Second War, and the pressure on women to apply their domestic skills to compensating was greater.

When women entered ‘men's trades’ and the armed forces in the Second World War they knew it had been done before, but like the previous generation they still experienced the amazing feeling of breaking new ground. It was exhilarating for women to take up ‘men's work’, although it provoked fear in men because it disturbed the status they were used to. The government and trade unions during the Second War learned from their mistakes and successes in the First when it came to organising women's employment, and took careful steps to ensure that women's ‘incursion’ into men's jobs was not permanent and would not lead to a drastic shaking up of family and economic life after the war. But no one could foresee exactly where the wartime development of industrial and military organisation would lead, and women's role in the forces in particular developed differently. In the First World War servicewomen had been largely confined to very mundane work like cleaning, cooking, clerical work, waitressing and some driving, to release men for active service. But in 1939–45 in addition to these jobs women handled anti-aircraft guns, ran the communications network, mended aeroplanes and even flew them from base to base. By 1943 12,000 servicewomen had been posted abroad. Although they did not in general fire weapons, women did jobs far more like men's than they had twenty-five years earlier. But the question was, would the experiences of participating in the armed services during the emergency and of doing men's work in industry lead to any lasting changes for women?

The distinctive features of the two wars necessarily led us to cover rather different ground in the two halves of the book. But another factor has also coloured the approach taken by each of us. The sources available to us are different. Many books were written about women's work during the First World War, though most of these, interesting as they are, were more concerned with looking at men's reactions to the women and the problems which might emerge than with describing women's own experiences. Only a few like Mrs Peel's How We Lived Then and Gilbert Stone's Women War Workers really gave women a voice. However, the Women's Collection at the Imperial War Museum gives an amazingly detailed picture of the jobs women did and includes descriptions written by the workers themselves. In addition, the War Work Collection at the Imperial War Museum's Department of Sound Records and the Oral History Project on Women's War Work at Southampton Museum give a much fuller picture of women's own views of work. But although these collections are immensely valuable, they are rather different from the material about women's experiences in the Second World War which is now available.

To begin with there are fewer survivors today from the First World War, so interviews done recently cover a narrower cross-section of women. Most of those interviewed by the Imperial War Museum and the Southampton Museum Oral History Project were very young during the First War, so the experiences recorded are those of girls in their teens and some young married women, but not those of older women upon whom the war must have made a different impact. Those interviewed about the Second World War, in contrast, include many older and married women. There are even some who worked in both wars. Most of the diaries and books written by women in the First World War came from the pens of young upper-middle-class women, like Monica Cosens and Vera Brittain, whereas there is a growing volume of memoirs and diaries about the Second War written by more ‘ordinary’ women from lower-middle or working-class backgrounds, like Doris White, Celia Bannister and Nella Last.

Also there was no equivalent of Mass-Observation during the First World War. Mass-Observation (M-O) was an organisation set up in 1937 with the aim of increasing knowledge about people's everyday lives and opinions at all levels of society, particularly amongst the great mass of ordinary people, especially women, of whom policy makers, employers and broadcasters typically took very little notice. M-O encouraged volunteers to write freely about their lives in diaries which they sent in regularly, and in other documents like letters and answers to the organisers’ specific questions (known as ‘directives’). The task appealed particularly to women, and several of the full-time ‘observers’ were women. The organisers used some of the material in their own reports and books published at the time, but the diaries, letters, directive replies and observations were stored in what became an immense archive where they are now available for researchers to consult. The M-O Archive provides a huge variety of frank accounts of what was going on during the war, from many viewpoints.

M-O operated in this way from 1937 to 1948 and it is no exaggeration to say that it was unique. Another more recent development has been the interest of television companies in making programmes about the Second World War. Penny had the good fortune to be asked to advise the team from Thames TV who made the programme Women as part of their series entitled ‘A People's War’, and was richly rewarded by being given access to the transcripts of interviews they had conducted with a number of women from all over the country who had a wide variety of war experiences. Age Exchange, a theatre company, has also interviewed a large number of London women about their lives and has published a lovely collection of extracts illustrated with wartime photographs, under the title What Did You Do in the War, Mum?. This material revealed a lot about what can be done with oral history. Women interviewed only about war work tend, naturally enough, to supply information only about their jobs, rather than their boyfriends, even though all sides of life are needed to give a full picture of a phase of women's history. It is to be hoped that oral history* projects will follow the lead given by Thames and Age Exchange, and tap more of women's memories of all aspects of their lives in both world wars as an urgent priority. There are sadly but inevitably shrinking numbers of women around to be interviewed about the First World War.

Although there are differences in the types of material we have used, we have both learnt a great deal from women's own accounts of their experiences in the two World Wars. That testimony goes a long way towards exploding myths which other historians have cherished about the part women played in the wars. The liveliness of the personal histories we have read and listened to, as well as the interest that women have shown in the fact that we have been writing this book, impressed upon us how important the wars, in all their complexity, have been for women in this century. We hope that this book itself will be part of the process by which these experiences will not be forgotten.

Part One

THE FIRST WORLD WAR

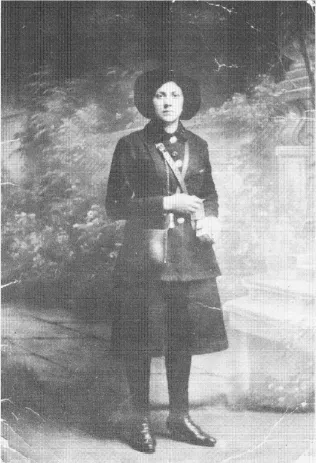

1 May English, a Southampton tram conductor during the First World War

CHAPTER 2

WOMEN BEFORE 1914

This chapter is about the kind of lives women led at home and work in the years immediately before the First World War, and we hope that the words of some of the women themselves, and their contemporary observers, will give life to this description. Women were to be found in diverse trades before 1914, and they certainly had problems which are still with us today – problems arising from the so-called ‘double burden’ of work and home, and from the belief held by many of their male co-workers, employers or observers that their work and their wages were not really ‘important’.

By the end of the nineteenth century the factory system was well-established but it would be a mistake to assume that all working men and women were factory workers. Unmechanised trades remained, like carpentry, metalwork, millinery and dressmaking to name but a few, and so too did agricultural work and domestic service. Britain was by no means fully industrialised by 1914 and the range of jobs available to women varied according to the areas they lived in. By 1911, about 29 per cent of the officially recorded labour force was female, and this figure remained about the same until as late as 1961.1

WOMEN'S JOBS

The textile industry was the largest employer of women factory workers. At the beginning of the twentieth century, there were 656,000 women working in textiles, most of whom were weavers or piecers, young women who acted as the male spinners’ assistants.2 To put these figures in perspective, there were a mere 15 women boilermakers at this time compared with 48,804 men. The cotton industry lay at the heart of the industrial revolution, and it remained the largest employer of women outside domestic service. Women were known as quick, neat workers, who did not expect such high wages as men, and although there were male weavers, they were outnumbered by women. In contrast, spinning was largely a man's job, and the men's unions intended to keep it that way. They used the excuse that the work of a mulespinner was too heavy for women, and that it was undesirable for them to strip down to cope with the heat and humidity as men did. Young women acted as assistants, however, and were increasingly employed on ringspinning, a lighter, less skilled trade, by the end of the nineteenth century, but there were few women spinners compared with the numbers in weaving.

Cotton weaving was important because it was one of the very few trades where men and women worked side by side for equal piece-rates. Men often operated additional looms (4 to 6 at once, as opposed to women's 2 to 4) and could make more money this way, but the rate for the job was the same, giving 22s–32s average earnings a week, for a 4-loom weaver, depending upon the quality of the cloth produced. This meant much to the women themselves, who often took pride in their financial independence. In addition, cotton remained one of the few factory industries where married women worked as a matter of course. Many other factory jobs were done almost entirely by young single women, who left work – voluntarily or otherwise – when they married or had children. In the cotton towns of Lancashire, it was acceptable for married women to go on working, and their wages were acknowledged to be important to the family income.

However, women weavers were concentrated in the north of England, and there was no similar tradition of r...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title

- Original Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- 1 Introduction

- One The First World War

- Two The Second World War

- 16 Notes

- Bibliography

- Index