eBook - ePub

International Production and the Multinational Enterprise (RLE International Business)

- 4 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

International Production and the Multinational Enterprise (RLE International Business)

About this book

The growth and impact of the multinational enterprise (MNE) in the post war period is one of the most important phenomena of our time. This volume, originally published in 1981 provides a comprehensive and detailed review of both the theoretical and policy issues at a time when the subject had reached a watershed, after the controversies of the 1970s.

The book provides a balanced discussion of major themes such as the development of modern theories of international production; the impact of the MNE on the nation-state and the structure of the international market; the response of governments and the appropriate framework for policy measures; and the historical context and likely future of the MNE.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access International Production and the Multinational Enterprise (RLE International Business) by John Dunning,John H Dunning in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Distinctive Nature of the Multinational Enterprise

I

Why is the multinational enterprise (MNE) a subject worthy of study by economists? What new insights do its operations and effects offer on the workings of the international economy? What distinguishes this institution from other economic phenomena?

One simple answer to the first question is the importance, and increasing importance, of the MNE in the modern world economy.1 Firms that engage in foreign direct investment – the broad definition of the MNE adopted by this book2 – accounted for one-fifth of the world’s output, excluding the centrally planned economies in the mid-1970s (UN, 1978). Their production, for some years now, has been growing at the rate of 10–12 per cent per annum – nearly twice the growth of world output and, outside the petroleum industry, half as much again as world trade.

According to Who Owns Whom, in 1976 there were nearly 11,000 companies which operated 82,600 foreign affiliates, a 20 per cent increase over a previous estimate of 9,481 by the Commission of the European Communities in 1973 (1976). Of this latter number ofMNEs, 371 operated in twenty or more countries; these were thought to account for more than three-fifths of all sales of MNEs. In 1977, some 27 per cent of the sales of 866 of the world’s largest industrial enterprises was derived from their foreign affiliates (Dunning and Pearce, 1981); of 381 enterprises with sales of more than $1 billion, 153 had a foreign content ratio (i.e. percentage of all sales, assets or employment accounted for by their foreign based activities) of more than 25 per cent, and 52 a foreign content ratio of more than one-half (UN, 1978). Some years ago, the liquid assets of all kinds of multinational institutions were estimated at twice the size of the world’s gold and foreign exchange reserves (US Tariff Commission, 1973); by the end of the 1970s, the corresponding figure was probably nearer three times. In every respect, MNEs are among the most powerful economic institutions yet produced by the capitalist system.

To these data may be added others which illustrate the role that MNEs, or their affiliates, play in the particular economies in which they operate. Again the facts have been well documented.3 To the home countries their importance is usually expressed, at a macro level, by the share of the gross national product accounted for by the foreign activities of domestically owned MNEs; and at a micro level, by the percentage of the sales, assets, profits or employment of a particular company or industry generated by foreign production. Table 1.1 gives some details of the proportion of sales of the world’s largest industrial enterprises accounted for by their overseas operations in 1977. It can be seen that the ratios vary considerably both between home country and industry, being highest among European nations4 and within the research intensive sectors.

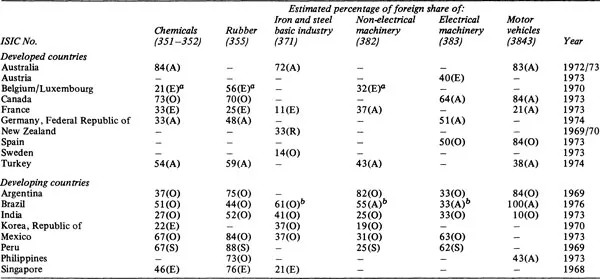

Table 1.1 The Foreign Content Ratio of 866 of the World’s Largest Industrial Enterprises, 1977

n.a. not applicable. n.s.a. not separately available.

Source: Dunning and Pearce (1981). Foreign content is defined as the percentage of sales of foreign affiliates of MNEs (excluding goods imported from the parent companies for resale) to the worldwide sales of the MNEs.

Outside manufacturing industry, though indigenous (and often state owned) enterprises are increasing their participation in the petroleum and some non-fuel mineral sectors (Dunning and Pearce, 1981), eight major MNEs still accounted for 30 per cent of the oil production of market economies in 1975; in copper, the corresponding share of seven principal MNEs in 1978 was 25 per cent; while in the same year six multinationals owned or controlled 58 per cent of the world’s bauxite capacity. More than one-half of all iron ore production in 1976 was accounted for by the seven largest multinationals (UNIDO, 1979). In several agribusiness activities, for example, tea, coffee, bananas, pineapples, sugar and tobacco, a few multinationals account for upwards of 60 per cent of the world output of the product in its natural or processed state. Lastly, in the services sector, most of the world’s leading banks, advertising agencies, hotels, airlines, auditing firms, engineering, petrochemical and management consultants, and construction companies have major and expanding interests outside their national boundaries. Increasingly, the world is becoming one large market place with the interpenetration of national markets by international production, supplementing, and in some cases replacing, that by trade.

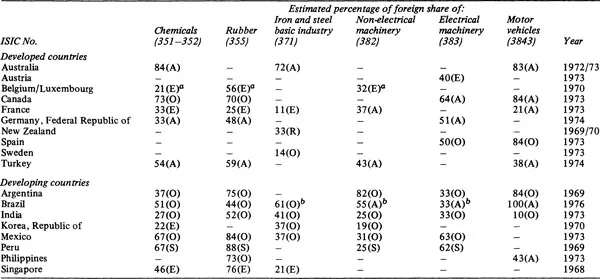

To many host countries, the contribution of affiliates of MNEs is a crucial one. In several economies, such affiliates account for more than one-third of the output of the manufacturing sector and/or one-half the output of their primary product industries. Examples include Australia, Belgium, Canada, Ireland, Norway and Sweden among the developed countries; Brazil, the Dominican Republic, Ethiopia, Fiji, Ghana, Honduras, Kenya, Malaysia, Mexico, Nigeria, Peru, the Philippines, Sierra Leone, Singapore, and Turkey among the less developed nations. The concentration of activity is most marked in import-substitution or export-oriented sectors supplying primary commodities, branded manufactured goods and skill-intensive services, and in which the market structure is oligopolistic. Some details published by the United Nations Centre on Transnational Corporations in 1978 are set out in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2 Indicators of Foreign Participation in Selected Industries in Developed and Developing Countries

a Employment by US majority affiliates.

b Based on the largest 5,113 enterprises.

O = Output, T = Turnover, R = Revenue, A = Assets, E = Employment.

Source: Table 111-63 of UNCTC (1978).

II

It is, however, less the distinctive characteristics of MNEs and more their distinctive behaviour, and the consequences of this behaviour for national and international resource allocation, which makes them of special interest to economists and policy makers. This distinctive behaviour stems from the fact that they directly control the deployment of resources in two or more countries and the distribution of the resulting output generated between these countries.

There are three near relations to the MNE; they are:

(1) The national enterprise which operates production units in different parts of the nation state in which it is incorporated, that is, the multilocation domestic enterprise. Like it, the multinational enterprise owns income-generating assets in more than one location and uses these, together with locally owned resources, to produce goods and/or services. As the affiliates of multi-location domestic enterprises possess certain advantages over their local competitors, due inter alia to their being part of a larger economic unit and the opportunities for specialisation this confers, so do MNEs enjoy similar benefits over national enterprises. But, unlike the multi-location domestic enterprise, the MNE owns and operates its assets and controls the use of its inputs in different national states, each of which is a sovereign political unit.5

(2) The national firm which produces in the country in which it is incorporated but exports part of its output, that is, the international trading firm. Like it, the MNE sells its output across national boundaries, thereby introducing an element of openness and interdependence in both the exporting and importing economies. Unlike the international trading firm, however, its activities involve a transfer of factor inputs and part of its trade is not between independent economic agents, at arm’s length prices, but within the same enterprise, at transfer prices, which, in so far as it is possible, will be fixed to serve the interests not of any particular affiliate but that of the enterprise as a whole.

(3) The national producing firm which exports part of its factor inputs, for example, material or human capital. Like it, the MNE exports income-generating assets but, unlike it, supplies these as a package deal and maintains control over the use made of them.

Likewise, the foreign affiliates of MNEs also may be distinguished from indigenous firms in the countries in which they operate. They have two near relations. First, firms which import factor inputs from foreign sources, and second, branch plants of multi-location domestic firms. In the first case, while both groups of firms are dependent on foreign source for (some of) their resources, only the foreign affiliates are controlled from abroad in the use of these resources. In the second case, both firms are part of larger enterprises, and so their activities are likely to be truncated in some way or another; the difference here lies mainly in the extent to which division of labour is practicable and in the inter-country distribution of the proceeds of the output.

Although it may be argued that these differences are ones of degree rather than of kind, and arise largely because the world is divided into a number of sovereign states, they do confer a certain distinctiveness on MNEs and their affiliates, the extent and character of which will vary according to, inter alia, the industries and countries in which they operate and their organisational strategies. However, wherever they occur, the response of MNEs and their affiliates to the economic environment of which they are part, or to changes in that environment, will, to some extent, be different from that of their near relations.6

Partly because of this and partly because some of the output generated by the affiliates of multinational enterprises in one country will accrue to the owners of resources in other countries, both the international allocation of resources and the distribution of economic welfare will be affected. Since the operating objectives of affiliates will be geared primarily to those of the enterprises of which they are part, rather than those of the countries in which they operate, clashes with host governments over some aspects of their behaviour are unavoidable. These clashes are likely to be most pronounced inter alia the more a country pursues a policy of economic autarky and hence the more the activities of MNEs are in response to market imperfections, for example, barriers to trade in goods, inappropriate exchange rates, etc., and the greater the differences in incentives and/or penalties imposed by governments which cause MNEs to shift resources, or claims to resources, across national boundaries.

III

To what extent do the distinctive characteristics of multinational enterprises necessitate modification to received economic analysis? Economic analysis is concerned with explaining the way in which resources possessed by economic agents are (or could be) used, and how the resulting output is (or could be) distributed. In so doing, it is interested both in the formulation of empirically testable hypotheses, and in advancing understanding about the relationship between economic phenomena. Economic policy deals with more normative matter...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables

- Foreword

- Part One

- Part Two

- Part Three

- Index