![]()

1 Images Begin to Sound

A Theoretical Framework

Does the spectator ever succeed in exhausting the objects he contemplates? There is no end to his wanderings. Sometimes, though, it may seem to him that, after having probed a thousand possibilities, he is listening with all his senses strained, to a confused murmur. Images begin to sound, and the sounds are again images. When this indeterminate murmur—the murmur of existence—reaches him, he may be nearest to the unattainable goal.

—Siegfried Kracauer, Theory of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality1

A PLAUSIBLE PSYCHOLOGY

It may well be that there is yet some truth in the claim—put forth by Gregory Currie in 1995—that film theorists have “misunderstood the relation between the symbolic and pictorial orders, and they have failed to produce a plausible psychology of the experience of cinema.”2 Rather than misunderstood, however, it may be better to say incompletely understood, and to note that the need for further theorization of the relation between the symbolic and pictorial orders appears particularly evident in the context of films that themselves draw attention to and problematize that relation.

By approaching psychoanalysis as a theory of the relationship between language, perception and memory, and simultaneously reevaluating the concept of cinematic indexicality as it emerges in certain writings in classical and modern film theory, the following discussion aims to take some steps toward fulfilling this need. In doing so, it does not intend to reconceptualize the “psychology of the experience of cinema” in an essentializing or totalizing manner, but simply to offer some explanation for the conflicted interaction between language and vision that recurs across the work of displaced filmmakers with a regularity that, as discussed in the preceding pages, can hardly be coincidental. It is not impossible, however, that some of the thoughts that emerge in this process may turn out pertinent to film theory more broadly and contribute somewhat to nuancing our understanding of the place of language in cinema.

In elaborating a psychoanalytic approach to film theory that diverges from its past and current permutations and valorizes the discipline's capacity to illuminate the role of language in visual perception, this chapter also indicates one potential path toward the alignment, within the film studies field, of the psychoanalytic concerns first popularized during the 1970s with the interest in neuroscience and cognitive psychology favored by more contemporary writings. As recent interdisciplinary developments indicate, the fields of neuroscience and psychoanalysis are progressively confirming their mutual relevance and thus even returning, as Avi Peled points out, to the latter's origins in Freud's neurological practice and the aims first set out in his 1895 Project for a Scientific Psychology (as well as, we might add, retrospectively establishing the validity of many of Freud's claims on brain function).3 The theoretical scope of this conjunction, potentially applicable across a range of film studies concerns, appears particularly evident in a context where the questions of language, memory and perception investigated by the two disciplines—often in mutually beneficial ways—assume an inalienable importance. Thus, while this study does not engage with cognitive film theory per se, its framework is underwritten by the support that recent research in neuroscience and cognitive psychology has given to psychoanalytic hypotheses regarding the mnemic and perceptual effects of language loss.

Particularly relevant, therefore, is the return here not—primarily—to those psychoanalytic writings already favored by film theory in the past, but rather to the discipline's largely physiological origins in Freud's 1891 On Aphasia, where, as Ana-Maria Rizzuto notes, his investigation into the representation of the body in the cerebral cortex and its recollection in language provides “the foundation for the essential concepts of psychoanalytic theory and technique.”4 In positing the link between word-presentations and thing-presentations at the heart of the symbolic relation, and exploring its break in aphasic patients, Freud's text has provided the basic starting point for virtually all psychoanalytic discussions of language loss. The following section of this chapter provides an overview of these discussions, while focusing in particular on the contribution of Julia Kristeva, whose writing has consistently addressed the question of the break between words and things—or, in her terminology, the symbolic and the semiotic—and its implications for psychic experience, psychoanalytic theory and artistic practice. Kristeva's relevance here stems not least from the fact that her elaboration of Freud's theory of aphasia emerges most specifically through her writings on exile and melancholia, both in themselves and in their many interconnections—a conjunction prompted, no doubt, by her own position as a displaced writer. We shall see, in addition, that Kristeva's sustained and influential theorization of the realm of the semiotic bears productively on the notion of cinematic indexicality.5

The questions opened up by the psychoanalytic theory of aphasia therefore allow us to elucidate the relationship between displacement and language loss, and consequently that between linguistic displacement and cinematic practice. The theoretical discussion that follows below starts by tracing a connection between Freud's definition of asymbolic aphasia and Kristeva's discussions of asymbolia, and thus the correlation between the semiotic and Freud's concept of thing-presentations. The place of the thing-presentation in signification and memory is further related to recent research into the cognitive effects of multilingualism, grounding the application of psychoanalytic categories in a discussion of linguistic displacement. Finally, the hypothesis (shared by Freud, Kristeva and a number of other writers) that the visual is the most prominent element of the thing-presentation serves to posit that the photographic index discloses an element of semiotic signification, and thus provides a means—both tentative and problematic—of reconstituting the bind between words and things whose asymbolic break can be said to define the experience of language loss. This point is further explored, in the chapter's concluding section, in relation to writings by Roland Barthes, André Bazin, Siegfried Kracauer and Pier Paolo Pasolini—an exploration that, amongst other things, reconsiders the enduring productiveness and relevance of certain thoughts first elaborated within the context of classical and modern film theory.

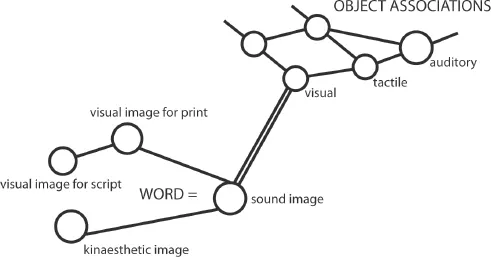

DISPLACEMENT AND ASYMBOLIA

As Valerie D. Greenberg points out in her highly informative Freud and his Aphasia Book: Language and the Sources of Psychoanalysis, the primary importance of aphasic syndromes for psychoanalysis “lies in the apparent similarities between communication disorders caused by brain damage and those resulting from disturbances of the psyche.”6 Although a number of observations made by Freud in this early work are pertinent to the present study and will reappear in more detail further on, the most crucial point lies in his distinction between verbal and asymbolic aphasia. In contrast to most late nineteenth-century studies of aphasia, Freud rejects reductive theories of localization, and instead develops a theory of aphasia largely based on a functional explanation of linguistic disturbances. Amongst his key points is the importance of the connection between object-associations and word-presentations, and it is precisely this that will make its way into his later theoretical writings. The core of his idea is illustrated by a necessarily reductive, but nonetheless useful, diagram (see figure 1.1).

More commonly known as motor aphasia, Freud's verbal aphasia refers to any disturbance between the single elements of the word-presentation, and as such bears little relevance to the present study. His definition of asymbolic aphasia, on the other hand, consists in an innovative appropriation of the term “asymbolia”7 to indicate a disruption of “the associations between word-presentation and object-association.”8 What is impaired is precisely the ability to connect an object-association (either present or recalled) and its corresponding word (-presentation). In this account, as John Forrester explains, “the sound image is the central aspect of the word: the primary meaning of the word is that meaning which was originally attached to it, when words were learnt from hearing them spoken. Similarly, the visual aspect of the object is the most important of the object-associations.”9 Freud's illustration of the object-association system includes the tactile and auditory elements—the text itself adds “and others”—and it is precisely to this heterogeneity that Kristeva will turn to oppose the openness of the “Freudian sign” to the closure of Lacan's (post-)Saussurean Signifier/signified.10 Kristeva's valorization of this heterogeneity is crucial to her theory of the semiotic and as such figures largely in this book. It is equally important that Freud himself places the visual at the head of the object-association, and that asymbolic aphasia thus becomes definable, in the broadest terms, as a disruption of the link between the predominantly visual object-association and the predominantly auditory word-presentation.

Figure 1.1 A diagram illustrating Freud's definition of asymbolic aphasia.

As noted above, recent research in cognitive science is providing empirical evidence that lends currency to at least some of Freud's hypotheses on aphasia.11 It is also thus contributing—as Jacqueline Amati Mehler, Simona Argentieri and Jorge Canestri point out in their seminal and still unique monograph The Babel of the Unconscious—to the study of multilingualism and language loss from the psychoanalytic perspective inaugurated in Freud's early work.12 Significantly, recent work on bilingualism suggests that naming pictures in a second language differs from naming pictures in the first language because of “effortful lexical retrieval.”13 Evidence for that suggestion is provided, to name one example, by a study in which fMRI technology was used to scan picture-naming processes in Spanish-English bilinguals. Picture naming in the second language relative to the native language revealed increased brain activity,14 leading the researchers to conclude that the results are “consistent with the view that picture naming in a less proficient second language requires increased effort to establish links between motor codes and visual forms.”15 Insofar as these (essentially commonsense) results refer specifically to the retrieval of words for the purpose of naming pictures, they appear to substantiate Freud's theory of asymbolic aphasia. That is, if the fundamental link between perception/recollection and language is, in Freud's terms, that between object-associations (in which, for him, the visual element predominates) and word-presentations, then the characteristics of asymbolic aphasia—a linguistic disturbance in which that link is at least weakened—are comparable to the increased effort to establish connections between “visual forms” and “motor codes.” In short, the effortful lexical retrieval encountered in a less proficient second language and relating specifically to visual stimuli might usefully be described as a manifestation, albeit a very mild one, of asymbolic aphasia.

Returning, in “The Unconscious” of 1915, to the categories formulated in On Aphasia, Freud renames the object-association “thing-presentation,” and introduces the new category object-presentation as the totality of thing-presentation and word-presentation. Although the term object-association has the benefit of drawing attention to the openness and heterogeneity of this concept in its original outline, it will be useful to revert, from this point, to its more enduring definition as thing-presentation—a term that bears the further advantage of standing in opposition to the conception of objects as already symbolized or symbolically denoted, as well as evoking the realm of the Thing (das Ding) so central to Kristeva's theorization of the semiotic. What “The Unconscious” reconfirms is that thing-presentations, whether perceived or recollected, do not in themselves have symbolic or linguistic value. The thing-presentation is first of all a trace, which might or might not enter consciousness by becoming cathected through linkage with a word-presentation. As Jean Laplanche and Jean-Bertrand Pontalis explain, it does not represent “the connotation of the act of subjective presentation of an object to consciousness. For Freud, an idea or presentation is to be understood rather as what comes from the object and is registered in the mnemic systems.”16 Thing-presentations are preverbal and, in the topographical sense, part of the system Unconscious, rather than the Preconscious/ Conscious; conscious representation, on the other hand, is composed of the thing-presentation and the word-presentation. Moreover, the work of repression, as stated in “The Unconscious,” consists precisely in depriving ideas/thing-presentations of their connection with word-presentations:

It is a general truth that our mental activity moves in two opposite directions: either it starts from the instincts and passes through the system Ucs. to conscious thought-activity; or, beginning with an instigation from outside, it passes through the system Cs. and Pcs. till it reaches the Ucs. cathexes of the ego and objects. This second path must, in spite of the repression which has taken place, remain traversable [. . .]. When we think in abstractions there is a danger that we may neglect the relations of words to unconscious thing-presentations.17

One of the effects of language loss is that it tends to lead speech or thought to occur precisely “in abstractions,” making us unwillingly forgo, as Freud warns, “the relations of words to unconscious thing-presentations.” The displacement into a new linguistic context confronts the subject with, on the one hand, unfamiliar words weakly corresponding to a restricted store of thing-presentations; on the other, a myriad accumulated thing-presentations with no way to emerge because the words that could cathect them are no longer as readily available as they once were. The problem is not only that thing-presentations are left without words, but that words are left without the thing-presentations that relate them to the subject's memory, to the unconscious traces that need to emerge when a word is heard or spoken in order for that word to be anything more than a phonic abstraction. If language activates the unconscious traces of memory-events, and if it is these traces that give meaning to the symbolic, then the problem is both that the loss of its symbolic counterpart leaves memory unsignifiable, and that the severance of the symbolic from unconscious mnemic traces leaves the signifier empty and meaningless. Hence the importance of Freud's observation in “The Unconscious”: mental activity moves simultaneously in two opposite directions—in the simplest terms possible, from words to “things” and from “things” to words. If this path in mental activity is disrupted, to whatever degree, the disruption will necessarily impact on both directions. Amati Mehler et al. posit the same concept from the perspective of multilingualism and language loss:

Affects, in themselves, are mute and [. . .] in order to find a decipherable communicative form for the self and for others, they must be united with an ideational representative. Inversely, whenever the superior mental functions—and perspicaciously verbal thought, whatever the language in which it is inflected—are not correlated by their relative affects, they remain only empty and colorless shells.18

At the same time, Freud's thoughts in the above passage from “The Unconscious” implicitly point to one of the fundamental problematics of language loss: namely, the possibility that the path leading to the unconscious thing-presentations might remain disrupted or foreclosed even in the presence of the words through which these thing-presentations are ordinarily activated. It is precisely in this sense that the effects of language loss can be seen to transcend the realm of repression: if it were merely a question of not being able to recall unconscious thing-presentations through discontinued use of the words linked to them, language loss, like asymbolic aphasia, would be definable in terms of repression. What the experience of displacement demonstrates, however, is that thing-presentations may be, and often are, severed from words even where these words continue to be used (this is made particul...