![]() Part I

Part I

Historicizing Pan-Africanism and the Contradictions![]()

1 Pan-African Theory’s Impact on the Development of Afrocentric Education in Jamaica

Jamaine Abidogun

Introduction

The impact of Pan-African theory on current Jamaican secondary education may be demonstrated by the extent to which Jamaican education incorporates an Afrocentric curriculum. Such a Pan-African educational approach may contribute to the formation of a national identity that consciously rejects Western knowledge as privileged knowledge. This chapter presents evidence of Afrocentric Indigenous Knowledge (AIK) within the Jamaican Secondary Education system. During the 1700s and early 1800s, the Jamaican education system consisted primarily of private or parochial schools that followed a British Western curriculum overseen by British colonial authority. Few Jamaicans of African descent entered into this system prior to the abolition of slavery in 1833. This early exclusion from Western education allowed for the emergence and maintenance of common Afrocentric indigenous education structures and practices. Pan-African theory, while initially tied to struggles for nation-state independence, would quickly expand its scope. To this end, Pan-African theory, in part, sought the recognition of African practices and so served to validate Afrocentric pedagogical practices, such as age grade training and apprenticeship that were already evident in Jamaican education. Through providing a brief overview of Jamaican education’s development, Pan-African theory’s dual role of identifying Afrocentric practices and reclaiming Afrocentric knowledge is demonstrated, as well as its later impact on the development of secondary education policy and curriculum.

Jamaica’s history positions it as part of the African Diaspora within the Anglophone transatlantic.1 Britain took possession of Jamaica from Spain in 1655, although actual political control did not occur until 1670. The Spanish arrived on Jamaican soil in 1492 and, within a few short decades, brought death through a combination of exposure to European diseases, torture, and forced labor practices to the original inhabitants, the Arawak Taino Native Americans.2

The British eventually used Jamaica to make significant profits from sugar production through a plantation system dependent on enslaved African labor. The steady influx of African people throughout the 1700s and

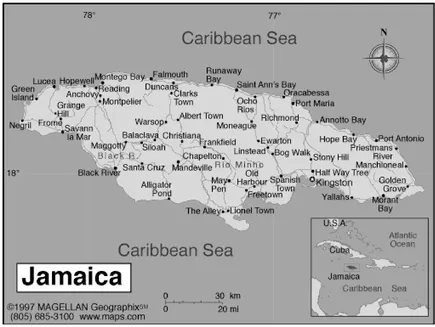

Figure 1.1 Map of Jamaica.

the first half of the 1800s firmly established Jamaica as part of the African Anglophone Diaspora. The push for emancipation of Britain’s Afro-Caribbean enslaved people was realized by 1833. This created problems for the sugar plantations as their costs rose, and they could not compete with neighboring Cuban and Brazilian sugar plantations. The abolition of slavery resulted in the need for paid labor. Many newly freed Jamaicans decided not to work for the plantations, opting instead either to cultivate their own land or pursue other crafts and trades for their livelihoods. This created a shortage of plantation labor that resulted in increased labor cost. In an effort to increase the labor supply and therefore lower its market value, Britain sent Africans from Sierra Leone to the West Indies. Between 1840 and 1850, approximately 11,000 “recaptives”—enslaved Africans rescued from slave ships—emigrated from Sierra Leone to the West Indies.3 These two waves of African immigrants (enslaved and relocated recaptives) wove together a distinctly Pan-African and Anglophone identity. Today, 90% of Jamaica’s population is of African descent.4

History of Jamaican Education

Jamaican formal education, like other British Caribbean holdings, was nonexistent for the majority of the population, who were enslaved from the 1600s through to the final realization of abolition in 1838. During this period, mission church schools were found on a few of the plantations. The major role of these plantation church schools was to “Christianize” and socialize enslaved people to accept a subordinate role in the society under White British authority. A few mission schools also existed for freed people during this period. These mission schools provided Bible training, basic literacy skills, and math training. These Protestant free missions spearheaded the Abolition Movement’s political maneuverings in this region. As the enslaved Afro-Caribbean people and their leaders initiated rebellions and protests throughout the islands, the British were forced to take serious consideration of these missionary political appeals. Most notable was the Jamaican rebellion on December 27, 1831,which began on the Kensington Estate and eventually spread to include 60,000 enslaved Jamaicans covering an area of 750 square miles. This rebellion was defeated by the British with colonial and Royal Navy forces and resulted in the deaths of 14 Whites and 544 enslaved Afro-Jamaicans. Even with this defeat, the reality and ongoing threat of rebellion, combined with missionary political appeals, culminated in the British Abolition of Slavery Bill, passed in 1833 and implemented on August 1, 1834. This bill effectively phased out all forms of slavery throughout the British Caribbean between August 1, 1834, and August 1, 1840, depending on the status of the enslaved person (i.e., agricultural workers, nonagricultural workers, children, etc.).5

From 1838 through 1885, mission schools continued and expanded as the primary source of formal education in Jamaica. During this time, the British began development in earnest of a formal education system, but it took until 1885 for them to actually establish their first primary schools. From 1885 to 1929, mission schools were phased out or converted to private schools as British formal education developed in Jamaica. Toward the end of the 1800s, secondary schools developed in direct response to the movement of British personnel out of the island and the need for increased participation by Afro-Jamaicans in white-collar (mostly middle-service) jobs.

In this early phase, the beginning of gendered roles within British-Jamaican formal education was apparent as more females than males sought employment through training as primary school teachers. Males continued to provide the bulk of manual labor. There were those few (mostly male) who could afford secondary education and earned scholarships to attend university in Britain or later to attend the University of the West Indies. This pattern of British colonial formal education development was repeated throughout most of the African Anglophone Diaspora with similar results. The primary difference was that in African colonial holdings, British education vied with indigenous education within individual ethno-nations. In Jamaica, these ethno-national identities were collapsed and synthesized over time, creating an Afrocentric pattern of indigenous education that operated within and alongside the British system.6

After independence in 1962, Jamaica initiated a system of 5-year Development Plans for education. Women continued to fill elementary schools as teachers and outnumber men in primary school populations. By the 1990s, females also began to slightly outnumber males in secondary schools. Yet going beyond secondary school to university had been and continued to be a primarily male privilege. Throughout the development of Caribbean tertiary education, a few noted Afro-Caribbean university-educated men became major Pan-African theory contributors and advocates as they developed and applied their theoretical interpretations to the Caribbean and the larger diaspora.

Caribbean Pan-African Theory

Pan-African theory in the Caribbean began its development in the late 1800s. The main focus at the start was political and economic independence within a framework of African unity. These early threads of Pan-African theory largely articulated a Western notion of nationhood based on Western education. There was agreement that the diaspora had its own civilizations, histories, and knowledge to celebrate, but early Pan-African theory varied widely in how African history and culture were understood, positioned, and articulated. For example, African-American Pan Africans, compared with their Caribbean counterparts, saw little need or value in incorporating Afrocentric knowledge in education until the 1960s. As Tony Martin explains,

Carter G. Woodson, Father of African-American History, considered Caribbean Africans to be ahead of their African-American counterparts in this respect. “It would hardly seem out of place,” Woodson wrote, “to remark that while the ‘highly educated Negroes’ of [the United States] oppose the teaching of Negro ‘culture’ these leaders of the West Indies are boldly demanding it.” [This was demonstrated at Marcus] Garvey’s 1920 First International Convention of the Negro Peoples of the World [that] had called for the teaching of black history in schools.7

This “Black history” or African history early on was often misrepresented as an exotic stereotyped African civilization with chiefs that held complete rule. The exotic stereotype sometimes presented through venues of Negritude and Negrista romanticized literature-conjured images of Africans who were sincere, strong, and sensual beings strongly connected to the earth, but with little concern for science or “rational” development of their societies. This fed from and into largely held European stereotypes of Africans. Rather than embracing the real history, culture, science, and so on of Africa, many Western-educated African Diaspora leaders (such as Leopold Senghor, Leon Damas, Aime Cesaire, and even initially W. E. B. DuBois ) often presented the anti-rational image of an exotic, natural African who could not or would not compete on par with Western notions of science and progress. Frantz Fanon’s explanation of the psychological impact of colonization and Du Bois’s sociological description of double consciousness were early explanations of these respective internal conflicts that hold validity in the present.8

African elites often promoted African independence while marginalizing African cultures and histories. At the same time, African-American elites often promoted “Black Heritage” but had difficulty identifying with their African homelands. They rejected Europe as the standard, but too often they either marginalized their respective African cultures or had little actual knowledge of Africa and its varied civilizations and histories to counter European opinion. The blame was not all theirs; after all, they were recipients of Western education. This internal conflict brought on by the colonialization process simultaneously contributed to the development of Pan-African theory (to counter Western knowledge and promote African knowledge) and neocolonial and internal colonial structures (respectively) that maintained Western knowledge as privileged knowl...