![]()

The demolition of the Palast der Republik (Palace of the Republic), the monstrous former East German parliamentary building in the historical heart of Berlin, finally began in February 2006, following a bitter tug of war that spanned nearly two decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall. The razing of the Palast took two years and became an urban spectacle just like its original construction and bizarre postsocialist afterlife. The Palast was closed down in 1990 for asbestos removal, shortly after East German representatives approved the treaty of German reunification in it. The building and its site were at the center of heated political debates and, despite the structure's disheveled and partially dismantled state, home to unconventional projects. The unexpected renaissance of the Palast began in 2004 when the remaining structure was opened for “interim use” and became an instant hit, especially with younger generations that had little or no first-hand experience of socialism (Oswalt 2005; Schrader 2005). It hosted innovative art installations, modern ballet and theater performances, film screenings, and all-night parties (Misselwitz et al. 2005). The offbeat boat tour in the partially flooded basement of the Palast, turned into a fantasyland of canals and small islands, was especially popular among tourists (Kimmelman 2008).

Despite the unforeseen success of the odd half-ruin, the German parliament never considered overturning the decision it made in 2003 to demolish the Palast and reconstruct the replica of the façade of the Berliner Stadtschloss, the Baroque Imperial Palace which occupied the site before the East German state blew it up in 1950 (see Figure 1.1).

It remains to be seen whether the post-1989 German state committed the same political mistake as the communist leadership when it decided to raze the Imperial Palace in 1950. There are quite a few uncanny similarities between the trajectories of the two palaces. The Baroque Palace of the Hohenzollerns was severely damaged in World War II. The East German government decided to dynamite the ruins because doing away with the building seemed like an easy and efficient way to deal with Germany's imperial past. But the bold move eventually backfired. First, many Germans classified this act among the worst crimes of the East German regime which they were determined to set right after 1989. Second, filling the void actually turned out to be much more difficult than expected. It took nearly 25 years and a long series of aborted projects to erect the Palast, during which period the prominent site functioned mostly as a parking lot. The monumental modernist block of the Palast finally opened in 1976, every bit of it flaunting the socialist government's conspicuous investment, including the display of imported Swedish marble and West German escalators, and lavish – well, by socialist standards – interior design (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.1

Berlin Imperial Palace in the 1920s.

The architects who were commissioned to design the building sought to revive the Volkshaus concept of the nineteenth century workers' movement in an attempt to combine political representative functions with public use, leisure, openness, and accessibility.1 In addition to housing the East German parliament, the Palast also contained a Congress Hall with 5,000 seats, 13 restaurants and cafes, two discotheques, several art galleries, a theater and a bowling alley, quickly emerging as the most visited entertainment complex in East Berlin. That the Palast was so enmeshed in everyday life, and not simply a clear-cut symbol of the state and totalitarian rule, is what makes many East Berliners deeply resentful about the post-1989 political treatment of the building (see Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.2

Palast der Republik in 1976 on the site of the former Berlin Imperial Palace across from the Berliner Dom.

The checkered history of the Palast der Republik underscores the central role of the state in matters of architecture and culture, and the thorny challenges facing architects who are expected to give lasting form to such politically charged projects. It is this intricate and dynamic relationship between the political agendas of the state and the intellectual programs of architects that constitutes the subject of this book.

ARCHITECTURE AND SOCIAL CHANGE

This book's central aspiration is to offer a novel perspective on processes of state formation by placing the transformation of the built environment at the center of the analysis. It investigates the changing relationship between politics and the built environment, power and design, state and architects in postwar Central Europe through the cases of Hungary and (East) Germany. Radical social changes throughout the twentieth century and the postwar political experiment of socialism render Hungary and Germany a unique laboratory to study this relationship. The following analysis shows how architecture was politically mobilized in the service of social change, first in socialist modernization and then in the postsocialist transition.

Figure 1.3

Palast der Republik during demolition in 2008.

Indeed, architecture in Central Europe has been a terrain, at least since the late nineteenth century, where competing social visions, utopian ideals, and national and cultural identities clashed and hoped to find material expression. Architects and statesmen often viewed architecture as cultural criticism and a vehicle for social change while aspiring to social engineering, as manifested in the monumental urban planning projects of the late nineteenth century such as the Ringstrasse in Vienna or Andrassy Avenue in Budapest (Moravánszky 1998; Schorske 1998) as well as in the ambitious social housing projects of interwar Vienna or Berlin (Blau 1999; Wiedenhoeft 1985). Architects have also considered their professional authority to lie not solely in technical expertise but in the interpretation of history, culture, and collective memory (Strom 2001). Architectural debates have therefore been intimately linked with social and cultural discourses about social reform, social modernization, symbolic representation of political systems, national identity, collective memory, and most recently the cultural impact of globalization.

Architecture is a “heteronomous” profession (Larson 1993: 5): it is located in an elaborate web of social, economic, and political constraints; it is exposed to the variegated exigencies of private and public clients (most importantly, the state), economic cycles, pressures of the construction industry, local technological conditions, and is often entangled in the slippery cultural politics of architectural aesthetics. At the same time, it is precisely this dependence on the social architecture of particular societies that turns architectural discourse and practice into an excellent site to probe the transformation of power relations.

Architectural styles and building types have even lent a vocabulary for compelling social metaphors used to denote social types, status groups, lifestyles, or power relations both in scholarly and everyday parlance, underscoring the very materiality of social arrangements. For instance, in the 1930s, the famous conservative Hungarian historian, Gyula Szekfű coined the term “neo-baroque society” to capture what he considered the essence of interwar Hungarian society: petrified social hierarchies reinforced by elaborate and artificial interaction rituals (Erdősi 2006; Szekfű 1934). Neo-baroque was one of several revival styles in late nineteenth century European architecture, which was inspired by the “proper” baroque of the seventeenth century, imitating its dramatic gestures and excessive ornamentation. Szekfű argued that unlike in Western Europe where Neo-baroque architecture fizzled out by the early twentieth century, in Hungary it remained the style of choice well into the 1930s. Neo-baroque architectural forms, according to Szekfű, embodied the empty formalism, servility and anachronism of Hungarian society that were packaged into complicated rules of etiquette governing social interactions between classes from dress code to greetings to forms of address. His term has quickly spread beyond academia and is used until this very day because it poignantly expresses the suffocating feudal rigidity and fraudulent mimicry of class relations as well as the cultural and political centrality of the figure of déclassé aristocrat, “the gentry,” in interwar Hungary.

Similarly, the postsocialist transition produced a new social type labeled the “prefab prole” (panelproli). Prefab refers to the large concrete blocks used for the construction of postwar prefabricated housing estates while prole is colloquial shorthand for a representative of the proletariat. A panelproli is an individual who lived in prefabricated socialist housing estates most of his life under modest circumstances and has been faced with downward mobility from working class to lumpen status since 1989. Its origins are debated but it catapulted to public attention in the television debate of the prime ministerial candidates in the 2006 Hungarian election campaign. It is used as a derogatory phrase primarily by commentators on the political right to stigmatize those who live in former socialist housing estates, insinuating that they have become poor through their own fault while idly lamenting the demise of socialist paternalism. The term also signals the increasing social degradation of socialist housing estates that used to be home to socially mixed populations. Both expressions show that material and social forms often cling together, and architectural markers carry crucial cultural, historical, and sociological information.

Since the late 1990s there has been an unexpected surge of interest in the material culture of socialism epitomized by the recent wave of Ostalgie, the burgeoning nostalgia for mundane relics of the socialist past. The term itself was coined in former East Germany and is derived from the combination of the two German words, Nostalgie and Ost, meaning “nostalgia for the East.” Although the trend has remained strongest in Germany and Russia, it also cropped up in all former socialist countries of the Eastern Bloc, becoming conspicuous by the turn of the millennium.

Ostalgie revolves around objects and environments that comprised the taken for granted structures of everyday life under socialism until they vanished virtually overnight in the wake of the collapse of the socialist system. At first, postsocialist citizens were ecstatic to discard what they considered the shoddy products of socialist design and industry and indulge in the cornucopia of Western-style consumerism. The initial euphoria, however, soon gave way to a sense of loss and longing for the familiar objects of the pre-1989 era. The ordinary objects of forty years of socialism (plastic kitchenware, furniture, apparel, even food items) suddenly became collectibles while ingenious companies were quick to relaunch old socialist consumer brands from Tisza sneakers in Hungary to Vita Cola, the GDR version of Coke, in Germany. In some cases, they even present serious competition to global brands. Remakes of old-time socialist goods are all the rage also for a younger local audience, and they are quickly acquiring a broad international appeal, as I personally witnessed when spotting trendy British youth in London wearing Tisza sport shoes, the answer of Hungarian sporting goods manufacturing to West German Adidas.

Ostalgie certainly attests to the power of built forms and physical objects as important vessels of collective memory and has increasingly captured the interest of scholars in various disciplines ranging from anthropology to comparative literature (Bartmanski 2011; Berdahl 1999; Berdahl, et al. 2010; Boyer 2006; Boym 2002; Jozwiak and Mermann 2006; Woodard 2007). In fact, due to the rising popularity of Ostalgie, the material culture of socialism is now explored primarily through the prism of nostalgia. The literature on Ostalgie, which focuses on the material objects of socialism as objects of remembrance, largely overshadows other historical approaches that give more emphasis to how these artifacts and spaces were fashioned and promoted as political instruments purposefully manipulated by the socialist state in the interest of shaping the social consciousness of its citizens and sustaining the legitimacy of the system (Betts 2010; Castillo 2010; Reid and Crowley 2000, 2002; Stitziel 2005; Urban 2009).

THE POLITICAL MEANINGS AND USES OF ARCHITECTURE

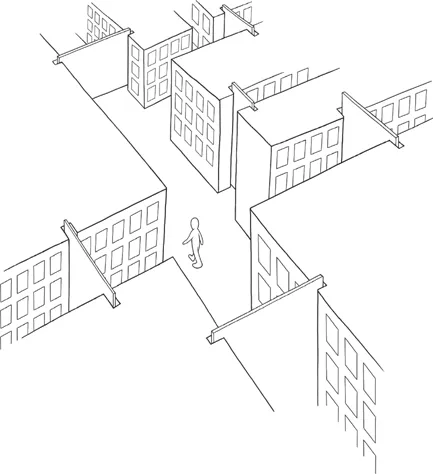

Yet, while former socialist clothing brands, furnishings, toys, and household items may have become romanticized and exoticized through postsocialist nostalgia and retro revival, the built environment of socialism continues to be deemed uniform and drab, therefore uninteresting, an apt reflection of a repressive regime (see Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4

Berlin, screenprint by Tomas Schats.

This book sets out to counter this popular view by peeking behind the gray façade to reveal a colorful struggle over competing meanings of the nation, Europe, modernity, and the past in a divided continent. The twentieth century was marked by a stern conviction in the power of architecture to fundamentally change social reality, best captured by Le Corbusier's famous dictum: “Architecture or Revolution. Revolution can be avoided.” It was assumed that radical new housing design would lift workers out of their culture of poverty and uplift society. To this, socialist states added the Marxist premise that material conditions determine social consciousness. Consequently, probably in no other political system did the state believe so thoroughly in the social-transformative role of architecture and architects as in socialism. The mobilization of architecture to radically reshape the built environment was a crucial component of state-orchestrated modernization programs while it was also deeply enmeshed in everyday life. This duality renders architecture a strategic site to understand the intricate ways in which cultural identity, collective memory, and social modernization intersect.

This book explores architectural discourse and practice in two important contexts, urban reconstruction (in the immediate postwar as well as in the postsocialist period) and mass housing construction campaigns in East Germany and Hungary under state socialism and its aftermath.2 These two contexts provide an excellent window onto the multifarious interactions between state, society, and architects. In contrast to the widely held view that assumes a static, top-down relationship between the state and professionals in authoritarian societies, this study unveils a fluid and complex picture whereby the changing priorities of the state result in frequent renegotiations of the boundaries between politics and expertise. These shifts lead to the constant redefinition of the public role of the architect as well as the substantive focus of architecture, creating new constraints but also new opportunities for architects to insert themselves into the political process.

I argue that although architecture remained consistently central to realizing the political objectives of the socialist (and postsocialist) state, the nature and meaning of architecture's role in state formation changed considerably over time. In the 1950s architecture served primarily as a tool of political propaganda whereas in the 1960s it was declared a weapon of social reform. In the 1980s it was viewed as a cultural medium through which these societies tried to regain their distinctive national and regional traditions in defiance of Soviet rule. In the 1990s architecture evolved into an important cultural strategy of urban development to tackle the dual challenges of globalization and the “re-Europeanization” of postsocialist states.

In mapping these changes my main goal is to show how professional discourse and practice are embedded in larger societal and political projects: the building of socialism after World War II, the launching and fizzling out of state socialist social modernization, and the challenges of postsocialist transformation: European integration and the ascendancy of a global economic system with its spread of a universalistic market logic.

The search for linkages between professional debates and broader societal visions reveals architecture to be a cultural arena where powerful definitions about modernity and tradition are constructed and contested. The social sciences abound in discussions of modernity that are often vague and blur the distinction between social modernization, aesthetic modernisms, and modernity as a historical project (Berman 1983; Frisby 2004; Heynen 1999).3 However, the explicit materiality of architecture renders debates about, and competing definitions of, modernity and tradition more immediately tangible and graspable than in other intellectual domains. As the architectural historian, Hilde Heynen aptly notes “architecture has the capacity to articulate in a very specific way the contradictions and ambiguities that modern life confronts us with” (Heynen 1999: 7). This is why architectural controversies are particularly well suited to expose the connections among the state-commanded process of socioeconomic modernization, the condition of living imposed upon individuals by this process, and the artistic and intellectual movements that address th...