![]()

Chapter One

Turn-of-the-Century Grotesque

The Uptons’ Golliwogg in Context

The Golliwogg books, beginning with The Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls and a “Golliwogg” (1895), were extremely popular annual Christmas offerings from Longmans, Green until 1909. Aware of the annual anticipation, reviewers sometimes expressed a “Here’s another Golliwogg book, it must be Christmas” resignation about them, occasionally shaking their heads over why the Golliwogg had taken over nursery life in the way that it had. But in spite of this prominent position in turn-of-the-century English children’s literature, present-day histories of children’s literature pay surprisingly little heed to the Golliwogg books.1 Given that the books had remarkable illustrations and influenced other works both technically and thematically, they were the first English picture books with a black protagonist, they had ubiquitous spin-off toys, greeting cards, games, dolls, and household items (“fortunes were made from the Golliwogg”), and the series inspired Claude Debussy’s popular Golliwogg’s Cakewalk and considerable affection from those who were raised in its era, this lack of critical attention is unfortunate.2 That the Golliwogg books are perceived as icons of racism as well helps to explain critical reticence but failure to study the Golliwogg seriously distorts its era in children’s literature, an era in which interchange between children’s culture and the adult avant-garde was particularly marked. The notable popularity of the Golliwogg motif when seen in its context suggests that this particular series said something significant to thinking adults as well as to children, that in its day it embodied the “spirit of the age.”

The series was originated by Florence K. Upton, then 21 years old, the talented daughter of a talented family of British emigres to New York state. Like a number of young women of her era, she was motivated by the desire to support her family, since her father had died in 1889, leaving her mother to raise four children by giving voice lessons. Upton had already been illustrating for four years when she turned to the idea of picture books while on a family visit to her relatives in London. She and her mother used the comfortable royalties that resulted from the Golliwogg series to take her siblings to Paris so that they could all receive art training, an enterprise that eventually resulted in her painting career. After her training, Upton continued to live and work in England, while the rest of the family returned to the United States.3

Upton painted from models, and before painting, she wired the figures (the wooden dolls are jointed and look much like artist’s mannequins) into the ludicrous positions they assume in the stories.4 Her mother, Bertha, then wrote the galloping verses that describe the illustrations. That the books were produced in this fashion, with verses following pre-existing illustrations, points to an extremely close collaboration between the mother and daughter, although they sometimes were not in the same country. Presumably plot notes by Florence must sometimes have accompanied the pictures, but the details of the working relation have not been documented.5

The characters in the Upton series are the Golliwogg character (a term Upton invented), the model for which was a black ragdoll from her childhood unearthed by a London aunt, and five Dutch (deutsch) wooden dolls of varying sizes. The original ragdoll, an American toy purchased at a fair with a leather face and rather stiff-looking body, had been mistreated (used as a throwing target) by the Upton children in Florence’s youth.6 He most closely resembles the Golliwogg of the first books—that is, he has thin lips and a triangular nose that bring a later doll hero, Raggedy Ann, to mind.7 The face of the Golliwogg evolved, eventually settling into gentler, more flexible features, but from the first he had a more attractive body and proportion than the original toy. Although Upton and others discussed his grotesque appearance, the pictured figure has pleasing compactness, flexibility, and decorative clothes. I think it is worth noting that though the original ragdoll’s clothing may have been those of a minstrel, the dress of Upton’s Golliwogg just as readily suggests the dress of the Bohemian artist, an allusion close to Upton’s life. The reference to the “artist head of Golliwogg” in the first book supports this suggestion.8

The stories themselves, picaresque adventures, are contained in oblong books of about 60 pages, which subsequently made them difficult to anthologize and thus more easily forgotten by children’s literature historians, even though the Golliwogg books comically interpreted for the nursery market many of the groundbreaking events of their time. After the first book, in which the characters meet in a toy shop on Christmas Eve, each begins with Golliwogg enthusiastically instigating a new, usually topical, adventure that the dolls must help him with:

You look astonished, Peg, my girl,

To note our summer goal,

But just as sure as you stand there,

We’ll find the great North Pole!

To reach it, you will have to climb

O’er fields of ice and snow

Where monstrous polar bears prowl round,

And lonely rivers flow.

Sarah and I have made our plans

To build a lovely boat,

She knows how strong it ought to be

On Arctic seas to float. (The Golliwogg’s Polar Adventure)9

They travel by bicycle, electric auto, and balloon, discover the North Pole in 1900 (ahead of the explorers—and also Winnie the Pooh), have a “kodak” tour of Africa (ahead of Teddy Roosevelt’s safari), and fight a war (unlike the Boer War, bloodless).10 The series also includes a visit to Holland (a popular site of children’s literature since Hans Brinker and a joke on “Dutch” dolls), a fox-hunt, the Golliwogg’s impersonation of Santa in a flying swan sleigh, a circus, a seaside resort (rather satirically treated), and a robinsonade.

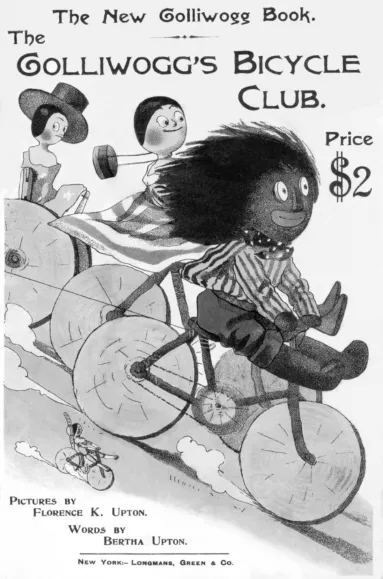

Figure 1.1 Florence Upton. Advertising flyer for The Golliwogg’s Bicycle Club (1896).

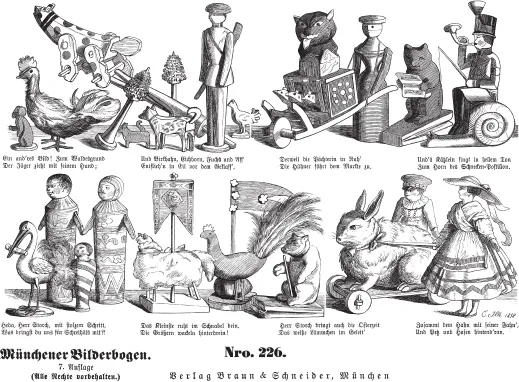

Figure 1.2 Detail of Number 226, Die Freunde aus der Kinderzeit, broadside by Eduard Ille, München, Braun & Schneider, 1858. Ille (like a number of English illustrators, including Upton) illustrated for a humor publication. In Ille’s case Fliegende Blätter (Flying Leaves).

All of the books involve whole-hearted exhilarating participation, a variety of elaborate costumes, catastrophes in which everyone crashes in spectacular ways, and suspenseful rescues of whatever member of the loyal band has come to grief. The Golliwogg, a big thinker and go-getter, is also a thoughtful and considerate friend.11 He is the accepted suitor of Sarah Jane, the second largest doll, who is a model of loyalty and competence. The other notable characters are the largest doll, Peg, who is sometimes malicious and always strong minded, and dauntless Midget, who is so tiny that her inclusion in the group automatically makes it look out of proportion and odd. Meg and Weg are medium-sized dolls with less individual character. Although the books are not difficult to understand, they are unusual. In our urge to puzzle over or censure the series, it is easy to forget that they were always very odd. Lively, sweet, and funny, they are a contribution to the grotesque in children’s literature, a particularly strong nineteenth-century strain that includes elements of the Alice books as well as many other English and German classics.12

And in embodying attributes generally associated with the grotesque, the books also combine fin de siècle ideas associated with two important artistic movements of the period. Jean Pierrot’s The Decadent Imagination 1880–1900, for example, identifies some of these qualities that tie the Golliwogg books more closely to this adult context.13 Pierrot associates the decadents with “allegiance to the most spectacular aspects of modernity,” such as Golliwogg’s auto-go-carts, airships, bicycles, and other topical inventions and pursuits. Pierrot also describes the decadents as “avid for acquaintance with foreign customs”—clearly also true of the Golliwogg as it is of characters in the nearly contemporary Oz books. And, of course, the decadents preferred the fantastic in art to Naturalism.14 In this series, however, it is not easy to distinguish between the forces of decadence and the forces that diametrically opposed it.

For example, the Golliwogg and the Dutch dolls, in their exotic qualities and their extremely animated manner are also allied with artists who rejected the decadent label. Indeed, the most obvious quality of the series is its exaggerated energy. The Golliwogg’s most characteristic mood is exuberant, and he is usually portrayed as working away at some task to accomplish his great aims.

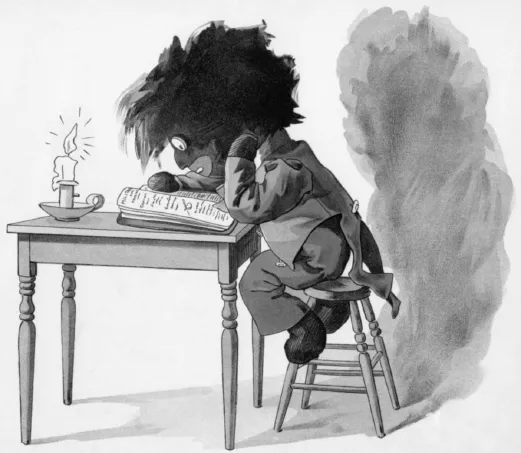

Figure 1.3 Florence Upton. The Golliwogg in War! Page 18.

Wilhelm Kayser’s The Grotesque in Art and Literature mentions the relation of the commedia dell’arte to grotesque, in that its nature cannot be assessed from its language “but only from the way in which it is acted or, better still, from the movements performed by the actors.”15 But it should be noted that Golliwogg’s enthusiastic movements, unlike those of E.W. Kemble’s turn-of-the-century stereotypes of black children, are more purposeful than amusing, and the slapstick elements are not limited to Golliwogg, but are also characteristic of the (white) dolls. Because of their jointed structures and their impetuousness, the Dutch dolls are even more humorous than Golliwogg, because his upholstered and fully clothed body looks more normally human, while many of their activities draw attention to their segmentation and literal woodenness.

It should also be noted that the Golliwogg and the dolls always overcome the difficulties of their situation. The universe is not nihilistic as it would be, for example, in a real clown routine. The friends race through adventures in which carnivores, mechanical devices, physical laws, social conventions, and their own sketchy plans threaten to defeat the company—but their spirit always triumphs. For example, when Golliwogg falls down the chimney on Christmas Eve and remembers, belatedly, that he could have just used the door:

But here a smile uplights his eyes

And dries his falling tears:

“This still shall be the happiest day

We’ve had for many years–

Come! leave this mess upon the floor,

Dear girls, we’ll have our ride:

I quite forgot the magic sleigh

Awaiting us outside!” (The Golliwogg’s Christmas)16

In other words, in their slapstick fashion their adventures are silly and bizarre but not seriously alienating. Golliwogg is considerably more capable than, say, Tristram Shandy, of controlling the malevolence of physical objects and restoring harmony. His energy is both amusing and positive, and both energy and childlikeness were qualities that interested the avant-garde artists of the period.

In connection with the end of the nineteenth century, many scholars have commented upon the widely held belief that European civilization was doomed and the European races degenerate.17 In response to the belief that mainstream European art was decadent and failing and that vital energy must be found elsewhere, many changes in literature, music, and art were attempted, especially those that sought to go outside what artists perceived to be established European modes. We are all familiar with the introduction of African sculptural forms in early twentieth-century art, for example, although this phenomenon was not the first indicator of the movement. In view of the insistenc...