![]()

1 Social imaginaries

How does the average Malaysian walking into any of the eating places along Jalan Bukit Bintang in Kuala Lumpur know what kinds of behaviour and acts are appropriate and which are not? Generally, menus of some kind inform customers what is on offer and the odd sign prohibiting smoking might remind them of what is now illegal, but otherwise there are few obvious instructions that tell individuals how to conduct themselves in the social practice of eating in company. Yet, most people know without being told that neither conducting one-sided conversations loudly over mobile phones nor leaning over to pick food from another customer’s table is acceptable. If such knowledge is attributed to good training and social etiquette, the question follows, how did social etiquette come to be? Who decided what is acceptable in the Malaysian context and how did they go about it?

On a day-to-day basis, we take our cue from those around us but nothing of what we read from how acts and practices are performed by others is written down anywhere. By and large this material remains in the background, unspoken except when we explain to children that ‘this is not how things are done here’. We take comfort from our skill in not drawing attention to ourselves through inept behaviour and take care to pass that ability on to our young. This same bank of knowledge also helps us to recognize when acts and practices previously considered appropriate, like the habit of using the spittoon or smoking in public places, become taboo.

The above examples may seem too trivial to require theorization but everyday social life is no simple matter. It is through these ‘fragments of social reality’ that ‘we are able to glimpse the meaning of the whole’ (Göle, 2002: 179). There are many bits of knowledge that people within the same social context carry that allow them to fit in with others and feel at home. The term used to describe the conventions governing acceptable as well as unacceptable patterns of behaviour as well as the various habits of speech and gestures that make up social life is public culture. Public culture is necessarily a function of the social space individuals inhabit. Therefore, it obviously differs from place to place and era to era, yet the processes by which public culture are formed remain unclear.

Public culture guides not just our modest, individual actions; it is also the foundation of our social practices. At every level, from the humble acts of everyday life to the broad ideas of political practice, tacit knowledge shared by individuals enables, guides and lends meaning to social life. To take another example from contemporary Malaysia, let us consider the eight demands of the Bersih movement: a clean electoral roll, postal ballot reform, the use of indelible ink, a minimal 21-day campaign period, free and fair access to media, stronger public institutions and a stop to both corruption and ‘dirty politics’ (Bersih 2.0’s 8 Demands, 2011). Where do these demands stem from and on what understandings are they founded? The demand of electoral reform rests on the notion of an acceptable electoral process that accurately represents the wishes of the Malaysian people.

Delving to a further level, the idea of an acceptable process can be said to be based on the concept of popular sovereignty where the legitimacy of a state and its government is derived from the general will of its people. A fraudulent, unfair and corrupted electoral process places said legitimacy in jeopardy. The eight demands of Bersih are a Malaysian interpretation of the broader concept of popular sovereignty. How did the concept of popular sovereignty, so deeply associated with the European origins of general will and consent (Rousseau, 2001), make its way into Malaysian society and gain enough relevance to move thousands of people to participate in three controversial rallies on three different occasions in 2007, 2011 and 2012? Those better schooled would point to their education but that is a privilege reserved only for some and as has been proven, participation in Bersih actions have cut through socio-economic and educational as well as ethno-communal differences in Malaysia. Still, that leaves the question of where everyday understandings of popular sovereignty originate from.

We seldom pause to reflect on how we know what to do every day repeatedly in multiple different situations without consciously having to reach for an instruction manual of some kind. Indeed, if we did consider too often, we might well feel paralysed by the options open to us. On the occasions we do wonder at the source of public culture, our reflex is to attribute it to custom, tradition, convention and norms. Does what passes for common wisdom evolve through happenstance or is there a system by which public culture is accumulated, habituated and then transmitted? What are the processes involved? At what point do ingrained habits become unsuitable within a social context and give way to new forms? Is this system a conscious or haphazard process? Who takes part in this process of evaluation? And finally, why does it matter at all?

It matters because what we understand of the system and processes by which we gain tacit knowledge frames our views of the world. Frameworks are broad structures that colour our individual and collective actions and the attitudes we take towards life. If, for example, we adopt a Marxian framework the assumption is that the rich and powerful are ultimately the ones who determine what passes into public culture. Such a framework would then compel an approach that analyses the relationships between new media and nation, the topic of this book, in terms of power.

Yet, as Prime Minister Najib Razak’s appeal to the Malaysian constituency that ‘street demonstrations must not be made a part of the Malaysian culture’ (Anis and Rahim, 2011) makes clear, agency – or the capacity to act – is not solely the privilege of the rich and the powerful. How elections have been conducted in the past in Malaysia and what, according to the Bersih movement’s conditions, they should be in the future also highlight that social practices are multiple in their enactment. On different occasions and under different conditions, for example, elections in Indonesia during the period of President Sukarno’s administration were vastly different from those during the administration of his offspring, Megawati Sukarnoputri (Leifer, 2000: 167). Although the idea of elections is common to many societies it takes on localized forms in accordance with the period and context of enactment. Within the ‘shared collective’ that ‘we invent together out of common experience’ (Arthurs, 2003: 582) to guide our social acts and practices, then, dwells a certain degree of flexibility.

To return to the issue of why frameworks matter, they matter particularly here because they lay the foundation of the approach taken in this study of the interaction and relationships between new media and nation in Malaysia. The theoretical framework on which this book is constructed is that of social imaginaries. The concept is developed here from the work of three theorists: Charles Taylor (1989, 2004), Cornelius Castoriadis (1987, 1997) and Alfred Schutz (1972, 1974). Put simply, the framework posits that each society possesses a unique social imaginary that informs its denizens’ actions and practices. The social imaginary is unique in the sense that the collection of knowledge that holds a specific society together differs from that of another. The Malaysian social imaginary, for example, would be different from the Indonesian one and despite certain similarities in history, distinct to that of Singapore. I define the social imaginary as the loosely co-ordinated body of significations that enables individual social acts and practices by making sense of them.

This chapter explains and develops the overarching framework for this book. It begins by laying out broadly what the social imaginaries theoretical framework is and then explains how it is synthesized. The framework lays the groundwork for the socio-historical approach taken up in later chapters for the analysis of the nation and new media in Malaysia. This then paves the way for the ideas, actions and practices associated with nation and new media to be regarded as products particular to the history and social, political, economic, cultural and other conditions specific to the Malaysian context.

Social imaginaries are basic and vital to all societies as they explain how public culture is produced, reproduced, transmitted and undergoes change. They perform the essential homogenizing role of helping individuals identify with their societies. At the same time, social imaginaries act like a store of customary solutions that individuals can turn to when they meet with problems that are typical to their society. In this sense, they relieve people of the burden of having to solve a problem anew each time they encounter it.

As developed by both Taylor and Castoriadis, the social imaginaries concept excels at explaining the world at the societal level. By virtue of being meta-theories, their connection with the minutiae of everyday life is limited. Nonetheless, in order to properly understand whence concepts such as nation and new media emerge from the socio-historical processes of Malaysia, it is necessary ‘to go back and forth between micro- and macro-levels of analysis, between empirical practices and theoretical readings’ (Göle, 2002: 179). This is where Schutz’s phenomenological approach to the structures that make up individual social worlds comes into its own. It brings to the framework a careful account of the processes that drills down to create an appreciation of how individual acts and experiences spring from our connection to the social world. Schutz’s work is revisited again in Chapter 5 where the relational matrix of predecessors, contemporaries, consociates and successors helps to explain the complex interactions between users and non-users of new media.

In a special issue of Public Culture published in 2002, various theorists published a set of articles themed around the idea of new imaginaries (Gaonkar and Lee, 2002). Their shared concern was with how we might grapple with the variances that develop in our world despite the seemingly homogenizing effects of globalization (Gaonkar, 2002: 18). One of the key ideas that emerged from Taylor’s contribution was the notion of multiple modernities, which was further fleshed out in the monograph Modern Social Imaginaries through the historical example of North America (2004). The basic argument behind the multiple modernities thesis is that each society creates a modernity that is conditioned by its particular historical circumstances and dominant moral order and is, as such, different. Rather than a singular modernity that sweeps across the whole world, then, the thesis explains each society via the context of its development.

In the same special issue of Public Culture, Gaonkar acknowledges the deep association of the social imaginaries concept with the work of Castoriadis (2002: 6–9). At the same time, Gaonkar finds Castoriadis’ psychoanalytical approach overly abstract in its preoccupation with ontology and for a meta-theory, problematically Eurocentric. Given Taylor’s critique of psychology as attempting to strip the self of the need for ‘strong, qualitative discriminations’ (1989: 32), it seems as though the work of Taylor and Castoriadis cannot be reconciled (Gaonkar and Lee, 2002).

I think otherwise and argue that commonalities do exist between the two. I have already pointed to their common societal approach. Additionally and importantly here, despite the difference in the language, grammar and process Taylor and Castoriadis use, for both, the individual is a production of the social. Ontologically, for each theorist, the notion that the individual emerges from rather than constitutes society is fundamental. Hence, although there is no doubt that extending such a framework to ‘nonclassical, non-Western, real-life contemporary’ Malaysia ‘thrusts theory into difficult new ground’ (Arthurs, 2003: 582), the possibility of gaining a better understanding of how a multiply divided society like Malaysia ‘holds together’ despite the ‘pervasive raggedness’ (Geertz, 1998) of the contemporary world is, by my reckoning, well worth the trek through tricky terrain.

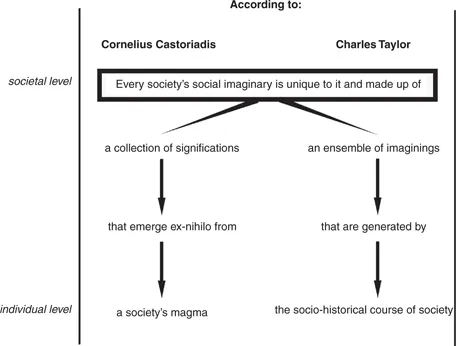

In what follows, I detail how Taylor and Castoriadis conceive of social imaginaries and the insights I draw from them to synthesize the framework used here. I draw mostly on Taylor’s work to construct the broad framework with some support from Castoriadis. The latter’s work informs the process whereby the constituents of social imaginaries, i.e. significations, are translated into acts and practices. Along the way I explain why I call the various elements that make up a social imaginary significations, and how Schutz’s work sheds light on the processes whereby significations enter into social imaginaries and are subsequently reviewed, renewed and discarded. Diagrams are introduced in this chapter to aid in the visualization of the connections made between the work of Taylor, Castoriadis and Schutz. They are crude simplifications of the theories and should not at any point be understood to properly represent the complexities of their work.

Theories of social imaginaries

Figure 1: Theory of social imaginary – Cornelius Castoriadis vs. Charles Taylor

According to Taylor, the social imaginary is ‘the ensemble of imaginings that enable our social acts and practices by making sense of them’ (Taylor, 2004: 165). Taylor explains the use of ‘imaginings’ (as opposed to visualizations and concepts) as the term most suitable to denote the ways in which ordinary people use images, symbols, stories and legends to imagine their daily existence and their relations to others (ibid.: 23). To illustrate, Taylor employs several political processes such as elections, demonstrations and protests as examples. The argument is that – like many socio-political practices – elections, demonstrations and protests only make sense and hold significance because individuals within a society share a common understanding of what is expected of them and each other, and both the norm and the ideal form of which a democracy consists. The Malaysian Bersih movement’s call for ‘clean and fair elections’ is based on another of the ideals associated with democracy, i.e. popular sovereignty. Towards the end of the last century, thousands of Indonesian protesters and demonstrators called on the egalitarian ideal of democracy when they ousted dictator President Suharto from his 30 years in office (P. Smith, 1999). In other words, some form of common if unspoken understanding always animates collective action. That same understanding, of living in or desiring democracy, also underlines everyday social relations between individuals in the same society.

Of course, it is possible that this kind of knowledge is formally taught in early life but subsequently absorbed, adapted and incorporated into an individual’s stock of tacit knowledge. In Western liberal democracies, for example, prior to an election, political rallies, blogs, televised debates, weekly media reports and polls are produced and conducted to allow candidates standing for election to disseminate information on their proposed policies and persuade voters to vote in favour of them. The classic example would be the US presidential elections held every four years. During the election, with the exception of postal votes, most individual voters turn up on the predetermined day, stand within a private booth or enclosure and make marks on an electoral form to indicate their choice of candidates and leave after slotting their folded votes into sealed ballot boxes. The ways of conducting an election campaign and casting and tallying votes vary in actuality from election to election (social media, for example, are a recent phenomenon first introduced as more populations access the Internet as a source of information), and they do not always operate in an ideally democratic manner. Yet, that is exactly where the power of the social imaginary as a concept manifests itself most clearly, for it not only guides the proper conduct of the election process, it also enables the recognition of improprieties, as per Bersih’s claims in Malaysia, in the enactment of what is jointly imagined and held as ideal. Once imagined, these imaginings can be enacted throughout a society.

For Taylor, ‘the social imaginary is that common understanding that makes possible common practices and a widely shared sense of legitimacy’ (Taylor, 2004: 23). It is the overall image contained within their shared social imaginary that provides participants in the election with the factual knowledge they need to stand for election, campaign and cast their votes as well as the normative knowledge which informs their awareness of what is acceptable in a democratic election and what is not. The social imaginary also allows individuals to make sense of their exercise of voting as constitutive of the employment of collective agency as a people, community or nation to choose a government by common consent. Coherence, meaning and legitimacy are thus lent to such a socio-political practice through social imaginaries.

Consider further the ideal of democracy in Malaysia. The Bersih movement is a major factor in the shift in the appreciation of what constitutes an acceptable election, but the model extends further than national, general or by-elections. This is evidenced in the lead-up to the 2012 campus elections at Malaysian universities where highly visible contests over how these institutions should be run were fought by students insistent on the need for transparency, independence and non-interference from political parties (Koh and Zulkifli, 2012). These events demonstrate how, once part of a society’s social imaginary, a concept such as democracy can take many forms and be enacted across various socio-political arenas and lend both meaning and legitimacy to socio-political practice.

However, Taylor makes the point that these occasional socio-political practices are not the only ones that social imaginaries enable. For Taylor, the social imaginary is ‘the “repertory” of social actions at the disposal of a given group of society’ (Taylor, 2004: 25). Acting as ‘social maps’, social imaginaries lend individuals an overall implicit understanding of their social existence by providing ‘background’ to daily life (ibid.: 25–6). So not only does the social imaginary make sense of our occasional socio-political acts, it also allows us to make sense of the everyday, mundane acts and practices that make up daily life: knowing, for example, when it is appropriate to strike up a conversation with strangers in a lift.

Profound or quotidian, social acts and practices such as general elections and crossing at traffic lights are only possible when a society generally abides with the tacit rules and indeed, only work when these social acts and p...