eBook - ePub

World Yearbook of Education 1986

The Management of Schools

Eric Hoyle, Stanley McMahon, Eric Hoyle, Stanley McMahon

This is a test

Share book

- 370 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

World Yearbook of Education 1986

The Management of Schools

Eric Hoyle, Stanley McMahon, Eric Hoyle, Stanley McMahon

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Published in the year 2005, World Yearbook of Education is a valuable contribution to the field of Major Works.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is World Yearbook of Education 1986 an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access World Yearbook of Education 1986 by Eric Hoyle, Stanley McMahon, Eric Hoyle, Stanley McMahon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1: Overview

1. The management of schools: theory and practice

Summary: Practitioners in school management have potential access to theories of education, educational policy, curriculum, innovation, management and organization. The chapter is concerned with the last three of these areas. Although organization theory and management theory have different intellectual origins and different orientations — the former essentially concerned with understanding, the latter with guiding practice — there has been much common ground. However, recent trends in organization theory have enhanced our understanding of schools as organizations but have diverged considerably from management practice. The relationship between the two remains strongest with the link between the concept of organizations as loosely coupled systems and contingency theories of management. This nexus has important implications for practice but the impact of theory on practice remains relatively weak because we have not yet explored fully the ways in which knowledge is generated, negotiated and utilized in professional practice and in professional training. The most promising approach in recent years has come specifically through approaches to the management of change which have created contexts in which head teachers and principals have engaged with substantive problems in collaboration with colleagues and professional peers, backed by various forms of professional support. Chapters in the World Yearbook of Education 1986 describe some of the most promising developments in this area.

Introduction

The growing preoccupation in many societies with the problems entailed in the management of schools can be largely attributed to the increasingly turbulent environment in which schools function. In North America there has been a longstanding concern with theory, research and training in the field of school management but in Britain and Europe, and in those Third World countries to which colonial systems of education have been exported, there has been much less interest in this domain largely due to cultural differences in attitude towards management in general and to the styles of leadership appropriate to schools in particular. Head teachers in these systems have not been expected to have had any training in management; experience as a teacher plus certain personal qualities, diffuse and undefined, have been regarded as sufficient for the successful head. However, there has been a steady growth of concern with management in Britain, Europe, Australia and the Third World over the past 20 years. The British Educational Management and Administration Society and the Commonwealth Council for Educational Administration have both fostered interest and activity in their respective constituencies. And such agencies as the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the International Movement for the Training for Educational Change (IMTEC) have sponsored research and development in Europe and the Third World on the management of school change. These trends have now accelerated and in many countries school management training has become a major element in governmental attempts to improve the quality of schooling (see Bailey, Chapter 16).

The increasing importance which is being attached to the training of head teachers has been stimulated in large part by the perceived need to equip them to cope with substantive problems with which schools have to cope. These problems differ from society to society, and are sometimes the exact reverse in some societies than others. Thus, while schools in many Western societies are having to cope with the problems of falling enrolments, schools in many developing societies are having to cope with rapid acceleration in enrolments. Some of the other problems which schools are facing include those social developments which are affecting the behaviour of young people (for example, substance abuse), the constant need for curriculum change (forced by high unemployment in many industrialized societies), the requirement that schools should seek to equalize opportunities for ethnic minorities and girls and, in newly independent societies, the problem of balancing a curriculum for nation building with the more universal needs of pupils (see Maravanyika, Chapter 15). Schools are generally experiencing much more direct political intervention than in the past, and the shrill demand for accountability is to some extent matched by the growing militancy of teachers at school level (see Lyons, Chapter 10).

It is assumed that training better enables the head teacher to make a professional response to these substantive problems and, if it is accepted, despite the doubts of some students of the professions that such a response involves recourse to a body of theoretical knowledge, one must ask what bodies of theory are available to the head and how these inform, or might inform, practice. The fact is that there are diverse theories available, including curriculum theory, organization theory, management theory, theory of innovation, etc, which are developed to varying degrees and related to each other somewhat loosely. We can explore further this range of available theory.

The theoretical basis of school management

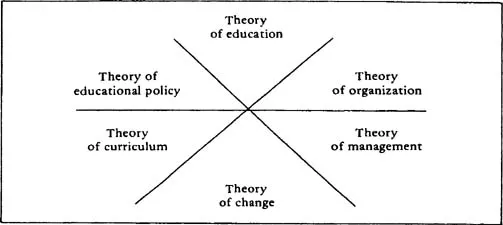

Figure 1 (see p 00) shows some of the areas of relevant theory. It must be immediately stated that this diagram is simplistic and used here only for heuristic purposes. Theory of education represents the most philosophical

Figure 1 Relevant theories

level. It includes theories about the ultimate purposes of education and is thus an enormous field. Theory of educational policy is concerned with what the general arrangements should be for achieving educational aims in a particular society at a particular time. It would include theories about, for example, states of transfer, the role of examinations, the schooling of minorities and the relationship between education and industry. Theory of curriculum includes all areas related to content and transmission. It could be further subdivided in many ways to include, eg, theories of learning and theories of pedagogy. The distinction made between theory of organization and theory of management may not be immediately obvious. However, as the distinction is discussed in some detail below, suffice it to say here that theories of organization are seen as being concerned with all the components of an organization (eg a school) while theories of management are concerned largely with one domain of organization centring on authority, decision making, etc. Similarly, one might quibble that the remaining vector, the theory of change, is really a subsection of management theory, and this is a perfectly reasonable point. However, an admittedly crude distinction can be made, not least because international initiatives in this area have ensured its more rapid development in many societies than broader aspects of management theory. Its affinity has often been more with theories of curriculum and their renewal than with management theory.

Insofar as practitioners draw upon theory, one may imagine that there will be variations in the degree to which individual heads will draw upon the different bodies. One can perhaps produce the sections on the above diagram as a sort of pie-chart with ‘slices’ of varying size, or of vectors covering different proportions of the equal divisions. For example, one head may give priority to educational theory, a vision of what education can accomplish, and be little concerned with, say, theories of management, while another may have a good organizer as a self-image and thus be concerned with management theory. In any case, the mix of theoretical concerns will, insofar as this influences practice, generate different styles. Hodgkinson (1983) in The Philosophy of Leadership has developed a model of leadership concerns of a much more sophisticated kind than the above and discusses various archetypes, eg the poet or the technician, which represent different priorities. However, these are heuristic categories, different in nature and intent from the research-based models of educational leadership of, say, Leithwood et al (1984) or Hall et al (1984).

Many of the substantive problems of head teachers, referred to earlier, would obviously involve recourse to the three distinctively ‘educational’ vectors, ie theories of education, educational policy and curriculum. It might well be that the training of heads should focus on these areas on the assumption that if the head can handle these issues the more ‘managerial’ tasks are of less importance and can be relegated to a minor concern. However, this chapter is concerned with the other three areas presented in Figure 1 and we can now turn to consider their nature.

Theories of organization, management and change

Organization theory and management theory have different intellectual origins. Organization theory is essentially a sociological tradition, with Max Weber as one of the founding fathers. Management theory stemmed from the writings of practitioners. However, the distinction is a crude one and over time there has been considerable intertwining between the two strands of organization and management theories with a degree of overlap sat a notional ‘centre’ from which the two traditions diverge. They differ basically in terms of range and function.

Organization theory is a broader type of theory. Organizational structure and management process are central components of an organization but still only two of a set of components. Organization theory is also concerned with cultural aspects of organization: symbols, language, the ways in which participants define their situation, etc, together with the micro-politics of organizations: the strategies which participants use in pursuit of their interests, and with the informal dimension of the organization; peer groups and their values, etc. Management theory is, on the whole, limited to a concern with organizational structure and the management process. However, there has long been a concern with organizational climates and, increasingly, an interest in culture and micropolitics is developing. Thus, there is a degree of overlap in the concerns of the two bodies of theory.

The different functions of the two types of theory can be indicated, in an admittedly over-simplified way, by conceiving organization theory as theory-for-understanding and management theory as theory-for-practice. Organization theory consists of a number of different perspectives by which we might better understand the nature of organization as social units and the reality of life in organizations. Organizations are objects of inquiry, and the organization theorist an interested but neutral party. Management theory, as a practical theory, is concerned with enabling the practitioner to improve the effectiveness of organizations and, simultaneously, the work satisfaction of members. Thus its focus is on organizational design, leadership, decision-making processes, communication, etc.

Of course, this distinction in terms of function is over-simplified. Organization theories are rarely value free. Organizational theorists naturally hope that their work will lead to improvement in effectiveness and satisfaction. However, within the category of organizational theory there is a great variation. Some theories are virtually indistinguishable from management theory, while at the other end of the continuum are those which are grounded on Marxism, critical theory or social phenomenology which are critical of the most fundamental characteristics of organizations. It is a moot point whether these should be termed organization theories’ at all, though they are certainly social theories about organizations (see Burrell and Morgan, 1979, for an excellent discussion of the full range of organization theories, and Willower, 1980, as well as Chapter 2 of this book, for a discussion of their place in the educational domain).

In dubbing organization theory theory-for-understanding one is not, of course, implying that management theory is not concerned with understanding. It would be foolish to seek to improve organizations without such understanding. However, whereas some management theories seek to embrace all organizational components, most are limited and, at the end of a continuum which stretches from the middle ground occupied by both organization and management theory, there are those theories which are highly mechanistic and unformed by ‘engineering’ models of organization.

The dangers of each type of theory for the practitioner are clear. Management theories can be so mechanistic as to be almost wholly detached from the realities of organizational life. One still encounters management theories which are splendidly rational blueprints for an unreal world. On the other hand, the understandings yielded by organization theory could easily bemuse and confuse the practitioner who tries to struggle with philosophical disputes within fields marked by an arcane scholasticism. One of the paradoxes of organization theory at the present time is that, as it enhances our understanding, it is thereby underm...