![]()

Part one

Introduction

![]()

1 Introduction

I Problem

(a) The problem

The problem before me is to construct an ideal-type model of Pukhtun1 society primarily from field-work data and based on the ideal Code of the Pukhtuns (Pukhtunwali). The central features of Pukhtunwali are locally perceived as agnatic rivalry (tarboorwali) and the preservation of the honour of women (tor). Honour and status are conferred by society on its members through acts approximating to the ideal especially in these two features. In the ideal matters relating to social behaviour and organization such as household settlements, marriage and expenditure patterns are also affected by Pukhtunwali. The discussion of the ideal-type will raise questions about the causal variables that create conditions among tribal groups for maintaining, or deviating from, Pukhtunwali.

I will attempt to illustrate the high degree of similarity between the ideological model and the immediate or empirically observed model. The study will attempt to prove that the behaviour and organization of social groups approximate to the ideal model. My main aim is to put forward the thesis that the ideal model exists within Pukhtun society when interaction with larger state systems is minimal and in poor economic zones.

My study further sets out to establish that Pukhtunwali continues to be operative for Pukhtun groups in spite of the severe constraints of an encapsulated situation implying different jural and administrative sanctions and various points of moral disjunction. Tribal Area Mohmands (TAM) will allow us to examine how the model appears in the ideal; Settled Area Mohmands (SAM) will provide an opportunity of actually testing the hypotheses by allowing us to view how the model behaves in an encapsulated condition. The complexity and extent of deviance from the model may be measured in the SAM situation and the thesis tested; verification or refutation of the thesis is thus possible.

(b) The problem restated

The study will examine tribal groups and their changing internal and external relations to exogenous economic and political situations. The thesis postulates that Pukhtunwali survives political and administrative encapsulation. Two groups of the Mohmand tribe will be examined to test the thesis, one, TAM, unencapsulated due to special administrative arrangements deriving from its geo-political situation and organized largely to approximate to its original tribal model, and the other, SAM, encapsulated within larger state systems. An examination of the problem will enable us to see how unencapsulated tribal social organization pre-supposes a political situation which in turn antecedes its form.

1 am distinguishing and conceptualizing two polar methods of encapsulation; the one I call encapsulation and the other ‘penetration’ based on tacit tribal agreement; the end results are often the same — integration of the smaller into the larger system. They are thus aspects of the same phenomenon. Encapsulation as discussed in general anthropological literature involves larger state systems based on different organizational principles encapsulating smaller systems, which does not preclude but does not necessarily imply the naked use of force. None the less it involves encirclement, absorption and enveloping, and provides the encapsulated society with little choice and limited strategies. It is therefore encapsulation both in a metaphorical and literal sense. It assumes larger and more powerful systems engaging weaker and smaller structures in which encapsulation is an inescapable factor and ineluctable destiny. The concept of encapsulation implies the absorption of a smaller system by a larger one and presupposes the surrender of a certain loss of identity of the former system. The terms and pace of encapsulation are decided by the encapsulators and their putatively higher civilization or culture with its symbols of dress, speech, diet, etc., is henceforth dominant (Bailey, 1957, 1960, 1961; Caplan, L., 1970; Caplan, P., 1972; Fürer-Haimendorf, 1939, 1962, 1977; Vitebsky, 1978; Yorke, 1974). In such situations ‘the modernizing elite may wade in regardless of the consequences and the cost’ (Bailey, 1970: 177). A certain moral disjunction of values is inherent in the situation which could either lead to integration or expressions of local self-assertion.

Anthropologists have seen tribal societies as passive recipients of exogenous pushes in the form of developmental and technical changes (Sahlins, 1968, 1969). I am arguing that TAM are not passive recipients of exogenous pushes. In the Tribal Areas military encapsulation failed over the centuries but from 1974 onwards began what can only be termed as economic penetration; it was encapsulation in economic terms but with major distinctions. The terms and pace were set by the TAM; the penetrators wore the clothes, spoke the language and ate the food of the penetrated. In a sense the encapsulators were allowing themselves to be encapsulated. However, this is palpably a temporary and strategic phenomenon for in the end the results will most likely be the same as that of the encapsulation of SAM, although the method has been diametrically different.

Encapsulation of tribal societies assumes the reordering of certain vital features of social organization such as settlement patterns, marriage rules pertaining to endogamy and exogamy, lineage politics and the two key components, tarboorwali and tor. The thesis will attempt to show that this is not always so.

It is axiomatic that social structural change can be measured or examined in relation to an anterior form of social reality. Hence the need to construct from historical accounts, case-studies and field-work data a model of Pukhtun tribal society. The economic situation predetermines the social situation and acts to underline the principles of agnatic equality, relationships which subsume agnatic rivalry. I will be showing through case-studies how social organization is affected by the geographical situation and economic constraints. For instance, shooting during feuds cannot last for more than a few days at a time especially when one party has captured the water-well, the key to the village, of the other party. Victory is then assumed and conceded and some sort of agreement invariably reached. A political point has however been clearly made, the point of lineage hegemony. The poor economic base, one half-nourished crop if it rains that year, along with their geopolitical situation, have brought together a combination over the last centuries to create three survival patterns for the tribals which help us to understand tribesmen and their strategy vis-a-vis encapsulating systems: 1 emigration; 2 unorthodox and often illegal sources of income such as smuggling and dacoity; 3 political allowances by encapsulating or larger societies in return for concessions in the form of penetration.

What then are the fundamental principles of Pukhtun social organization? The underlying principles are threefold and interconnected: the primary principle rests on tarboorwali which in turn crudely ensures a ceiling to the wealth and power an individual may accumulate and therefore more or less forces the second principle, which is an intense spirit of democracy that finds ratification in the tribal charter. The third principle is that of honour deriving from certain features of the Pukhtun Code particularly regarding women and their chastity (Chapters 4 and 7). The model as built through the case-studies reveals a man’s world in the most chauvinistic sense of the concept. There is manifest and constant glorification of machismo. The entire concepts of Pukhto revolve round the concept of manhood (saritob) and honour which in turn involves man’s ideal image of himself. The highest compliment is ‘he is a man’ (saray day). The three key and prestige conferring symbols of tribal society, the male guest house (hufra), the gun (topak) and the council of elders (jirga), are exclusively the reserve of Pukhtun males. In the most profound sense it is a man’s world.

The central issues in Pukhtun society revolve around the pursuit of power, status and honour, a pursuit that is closely related and limited to agnatic kin on the tribal genealogical charter. The symbolism of unilineal descent from a common apical ancestor is effective in articulating a great deal of the organizational functions of these groups. As I hope to illustrate in the study, the operative segment of the tribe which defines the genealogical and geographical boundaries, the arena of conflict, and produces its leaders and alliances, is the sub-section. I shall analyse tribal social organization and political activity in terms of the sub-section as the operative lineage. The single most important feature of society with far-reaching socio-economic ramifications is that of agnatic rivalry. As Freudian man is charged with hostility towards his father and Malinowskian man against avuncular authority, the object of hostility to the Pukhtun is his Father’s Brother’s Son (tarboor).2 The answers to questions underlying both psychological and sociological motivation invariably lie in agnatic kin or tarboor relationships and at the core of the concept of agnatic rivalry translated in society as tarboorwali. There is thus a significant dividing line between true siblings and classificatory siblings. ‘Balanced opposition’ in tribal structure means the opposing subgroups of cousins, usually of that generation.

The Pukhtun model presupposes that politics is a central activity involving competition for power and as a mode for acquiring honour and status in society. I will be arguing that Pukhtunwali survives and that its main aim is political domination at a certain lineage level and not economic aggrandization. Political domination gives political status which in turn affords access to political administration, which may or may not give direct economic benefits. The implications for agnatic rivalry are obvious: while appropriating power agnatic rivals are excluded from it. It is a ‘zero-sum’ situation (Barth, 1959). The structure of political domination is at once a behavioural and an ideological phenomenon. Briefly, the problem concerns the Pukhtun view of his world and the changes set in motion within it as a consequence of encapsulation. Deviance from and compromise of the Pukhtun model are social mechanisms of adjustment. The awareness of deviance poses an acute dilemma for the Pukhtun: either he rejects his Code or removes himself to those unencapsulated areas where he can practise it. The dilemma is still unresolved, as the study will illustrate.

Tribal life on varying social and political levels is a constant struggle against attempts to capture, cage or encapsulate it by larger state systems. However, it is already totally imprisoned in the bonds of its own Code. For SAM the test is severe; the Code still survives to an extent in the face of the rather shabby symbols of and feeble attempts at encapsulation. The encounter debilitates the tribal system by attacking it at its most vulnerable and yet vital spot: the Code — the very core and essence of Pukhtunness and that which forms and defines a Pukhtun. In this encounter there can be no synthesis, no harmonious absorption of one system into another; there can be only stages of rejection. I am arguing that SAM is an aspect of TAM as a consequence of political operations.

I will show how lineages, particularly the operative lineage, interact with each other in conflict and alliances around the concept of tarboorwali through extended case-studies from TAM and SAM over three and four generations (Chapter 7). How one lineage emerges and in direct proportion the other lineages decline, resulting in changing settlement arrangements, marriage patterns, economic and political activity, is thereby made clear (Chapters 8 and 9). The important variable is the interaction with the colonizing power and its vast resources (Chapters 3, 5 and ). Administrative patronage confers status and income as it creates a broker role for the Maliks (petty chiefs or headmen). Another important factor is the expulsion from the Tribal Areas into the Settled Areas of groups who over two or three generations make their fortune, first as tenants then as subinfeudators and collaterals of land, and return to reinvest it in the continuation of lineage feuds. In short, I shall show the relationships of lineages to changing political situations, which, in turn, involve changing attitudes towards each other and towards social and cultural values. Pukhto is still spoken (wai) but more difficult to do (kai). I will relate the shifting lineage positions and conflicts to encapsulating systems and, in turn, to tribal strategy, which will illuminate theoretically how lineage structures and Pukhto concepts undergo changes as a result of such encounters. Part of the thesis involves the concept of encapsulation which in turn brings with it the awareness of Mohmandness in the act of migration, an awareness successfully manipulated for political or professional purposes, as I shall show through case-studies (Part Three).

The total period during which I was studying the Mohmands, between 1974 and 1977, confirmed part of my thesis that Pukhtunwali survives in its ideal form if given the right ecological environment and the condition of political unencapsulation. With changing economic factors, such as development schemes bringing new sources of income and a form of encapsulation through penetration, values even in TAM have begun to change (Part Three). In 1973, the year the development schemes began, the last agnatic killing was committed. A certain correlation is apparent. If the peace in Shati Khel becomes a permanent condition it would, paradoxically, imply deviant Pukhtun behaviour if we are able to refer to the ideal-type.

However, the thesis that Pukhtun social structure and Code survive encapsulation is partly refuted and partly substantiated by the very application and nature of the model in TAM and SAM respectively and its geo-political requirements, as I will show. Diachronic analysis of the model will enable us to examine the historical and structural circumstances of its appearance, reproduction and, finally, processes of alteration and reduction in SAM as epiphenomenon. The two important features making for its empirical validity are the stability of the model and its capacity to reproduce itself successfully over some four centuries at least. These features provide the basis for the formulation of the problem: what social and cultural criteria determine the transmission of values from one generation to the next? Or, through what social mechanism does a society prevent breakdown of transmission in the face of encapsulating systems that herald social and economic change? The answers are central to my study.

II Methodology

(a) Method in the field

The study will be worked out within a framework of Pukhtun life that includes both the grand symmetry of tribal lineage structure with its varying and interconnected arches and spans, and also, on another level, the trivia and minutiae of daily existence: the cold geometrical arrangements and precision of anthropological tribal lineage charts combined with the smells and sounds of everyday village life. I will not be concerned only with the area of the village, heads of animals, extent of rural credit, lineage charts, etc., in themselves, but as part of larger structural arrangements of social organization. I wish to present the whole range of ethnographic data reflecting the humdrum of everyday life that the average informed reader may wish to see for himself in order to learn about the Pukhtuns, but at the same time I will order the data in such a manner as to illustrate clearly the underlying principles of Pukhtun social organization. The former without the latter is to my mind heuristically an unrewarding and even incomplete anthropological exercise. But the latter without regard to the former risks the danger of becoming a rarified model and losing touch with social reality.

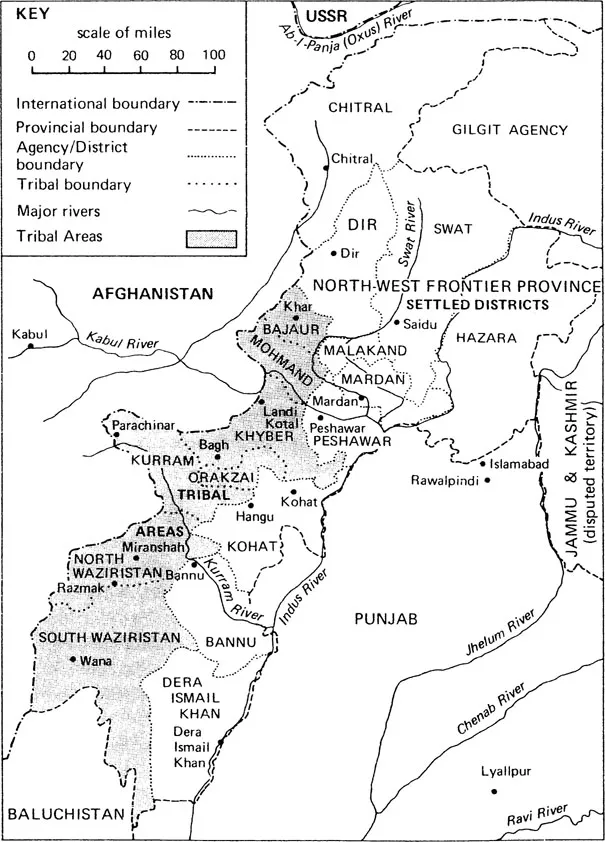

First, a few words about my field-work areas. It is important to understand clearly the distinction between Tribal Areas and Settled Areas, as it provides the basis of division among the Mohmands with far-reaching ramifications. The Tribal Areas of the North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan consist of seven Political Agencies (Map 1). They differ from the Settled Areas in that:

Map 1 The North-West Frontier Province of Pakistan

(1) no criminal or civil procedure codes of Pakistan apply;

(2) they are not subject to the payment of taxes or rents of any kind. Many peripheral Islamic tribes like the Kababish Arabs pay taxes (Asad, 1970:154) and ...