![]() Part One

Part One

The Radical Function![]()

Chapter I

Asking the Question: A Review of some Theories of the Formation of New Concepts

People have been trying to explain the emergence of new concepts for over two thousand years. Writers of almost every kind have been at one time or another concerned with it: philosophers, theologians, psychologists, physical scientists, poets. The history of their theories ranges from Plato to Saint Augustine, from Bacon and Descartes to Hartley, Hobbes, Locke, and Hume; from the Romantic poets of the nineteenth century to Bergson, Freud, and the Gestalt psychologists. In our own time the body of literature on the subject has reached epic proportions. American industry, for its own reasons, has developed a kind of manic preoccupation with the subject and many writers from the academic world, largely in one or another of the social sciences, have reflected industry's concern.

In spite of the abundance of the literature and the innumerable contributions that have been made, theories on the subject fall into one of two categories: either they make the process mysterious, and therefore intrinsically unexplainable; or they regard novelty as illusory and, therefore, requiring no explanation. These themes are readily apparent in writings from Plato's time. In our own time they are less apparent but equally powerful.

This division reflects a similar division in the history of attempts to account for metaphysical novelty, novelty in the world itself. In both cases the tendency either to obscurantize or to explain away novelty reflects the great difficulty of explaining it. The difficulty comes in large part from our inclination, with things and thoughts alike, to take an after-the-fact view. This after-the-fact-ness in theories of the formation of new concepts has tended to keep from investigation a kind of process which is central to this subject matter: the process of metaphor or, as I will call it, the displacement of concepts.

In this chapter some of the dominant theories of new concept formation will be examined, illustrating the division mentioned above. Some exceptions will be noted as well. I will need to begin, however, with comments about the notion of "new concept' itself.

New Concepts

It would be comforting at this point to be able to offer a definition of 'new concept' which would carry through the capsule history proposed in this chapter and through the rest of the book. Unfortunately, the writers to be discussed use "new concept' in many different, and some inconsistent, ways. The most that can be done, therefore, is to make some of the crucial distinctions and to block out some of the areas of the subject that will be of greatest interest.

I want to use the word 'concept' broadly enough to include a child's first notion of his mother, our notion of the cold war, my daughter's concept of a thing-game, Ralph Ellison's idea of the Negro as an invisible man, the Newtonian theory of light, and the idea of a new mechanical fastener.

These are all concepts as we ordinarily use the term, and as I want to use it. Whether they are to be regarded exclusively as language, behaviour, images, logical terms, or the like, is not the issue. These are all ways of looking at concepts which may from time to time be useful. However, there is an underlying model for our thinking about concepts which is at once quite general and quite harmful. It has a traditional place in philosophy and psychology and it is enshrined in our language.

When we say that we 'have' a concept, that it is applied' to an instance, that it 'fits' or does not 'fit' that instance, we speak as though a concept were a kind of concrete thing. We speak of 'big' and 'little' ideas, 'my' idea and 'yours', 'few' or 'many' ideas. We spatialize ideas. We give them a certain generality—a single idea may 'apply' to many instances—but we speak as though they had definite limits and could be handled like spatial things. It is as though we thought of concepts as mental stencils superimposed on experience.

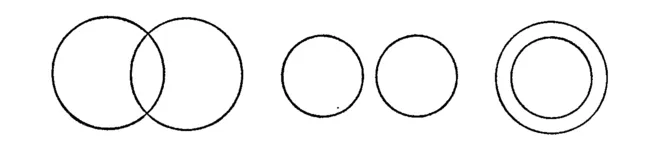

This way of thinking is characteristic of traditional logic, in which concepts are thought to refer to sets of properties (the 'intension' or 'connotation' of a term) which define classes of objects. These classes may be related to one another by inclusion, exclusion, overlapping, or any of the kinds of relation permitted by the familiar Venn diagrams.

While the Venn diagrams are a technique for manipulating concepts in their logical relations, they are also a symbol of the essentially spatial way in which concepts, in traditional logic, are conceived. As Bergson showed, this makes change of concept, the dynamic character of concepts generally, almost impossible to imagine.

Fortunately, there is, in writers like Dewey, C. I. Lewis, and Wittgenstein, another way of looking at concepts. Here concepts are seen as tools for coping with the world, for solving problems.

In our ordinary commerce with the world, we come to generate certain expectations. In the laboratory a new liquid is discovered. It is transparent, viscous, corrosive to the touch. We form a certain sensory Gestalt of it. Gradually, in our dealings with it, we learn what to expect. It flows in certain ways under certain conditions, it behaves in certain ways when heated, it combines with various compounds, it has certain characteristic reactions to radiation and so on. In our learning, we are able to relate it to many other familiar concepts. This, in a shorthand way, provides us with many other expectations. Our concept of the liquid is just this learning about it, just this set of funded expectations. It is indefinitely great, fuzzy at the edges, and constantly changing.

Language is an internalized, stimulus for this body of expectations. When I say, to others or to myself, 'This is an acid' or generally 'This is an x', I awaken these expectations. I am able to deal with the thing. I can bring to bear what I have learned to expect of it.

This way of thinking about concepts, as Dewey showed at great length in his Logic (1938), relates our conceptual behaviour to animal learning generally. The verbal side of a concept is shorthand for our learning about an area of experience. This shorthand, these expectations, are things we use in our commerce with the world, and they can be understood and evaluated in ways analogous to our understanding and evaluation of other things we use. This much Dewey and Wittgenstein have in common.

C. I. Lewis (1946) has formalized this view in his theory of judgement. Every judgement about an object he analyses into a series of judgements, indefinitely long, each of which is of the form, 'Given a certain sense experience, if I act in a certain way, then I can expect to be presented with certain other sense experiences.' It is always only arbitrarily that I bring to an end the list of expectations associated with my concept of a thing.

From this point of view, the 'intension' and 'extension' of a term are abstracted from the expectations and behaviour which make up a concept. They are taken, as it were, from the outside. If we observe the situations in which we use a term and bring into play the expectations associated with it, we begin to enumerate its extension. If we choose from the mass of expectations involved those which characterize all and only cases in which the term is used, we give its intension. In formal systems, the attempt is made to limit concepts to their extensions and intensions. Otherwise we must understand intension and extension as limited and rather arbitrary selections from among the expectations that make up the concept and the conditions under which they are brought into play.

It is sometimes useful and interesting to abstract concepts from the situations in which they are used. They have generality in the sense in which tools have generality. They may be used in more than one situation. Abstracted from their situations of use, they can be looked at as forms or Gestalts. They are, in this sense, structures developed in our experience and they are entirely analogous to perceptual forms. Of the many points that could be made about this Gestalt character of concepts, I want to emphasize the following:

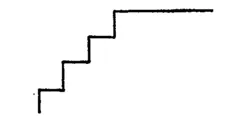

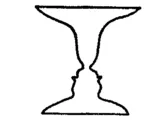

The situations we conceive in a certain way can be conceived, in an indefinite variety of other ways as well. This fact stares us in the face whenever we look at what happens in the formation of new concepts, even though the inertia of our conceptual systems, once established, is so great as to make us almost incredulous about it. A lamp is a lamp, after all. A typewriter is a typewriter. It is a great advantage of the famous Gestalt figures that they make the point vivid and stubborn.

1. is a staircase, or an overhanging ledge.

2. is a bird or a rabbit.

3. is a vase, or two faces in profile.

Once having resolved a problematic area of experience, once having found a way of looking at (and therefore dealing with) a situation which was at first novel and puzzling, our impulse to stick with it is overwhelmingly powerful. We have 'adapted' to it, and through it. Our concept-forming apparatus operates under a categorical imperative of'let well enough alone'. It is at once a reflection of this tendency, and a protection of it, that we are apt to regard our ways of looking at things as inherent and immutable in the things themselves. But the formation of new concepts always requires us to break these settled ways of looking at things, to 'come apart' with respect to them, prior to the formation of a new concept.

Given what has been said above, concepts are to be distinguished from their instances, from the situations to which they apply. But this is a distinction rather than a separation. At a given time, everything is what it is in terms of the concept or Gestalt under which it is understood. There are no things without concepts. It is only by a process of abstraction that we distinguish between concept-tools and the situations in which they are used. While a given situation can be conceived in a variety of ways, it is always a concept-structured situation. There are no observations, data, perceptions, objects, independent of concepts. We cannot even name things without giving clues to the concepts which make 'things' of the situations confronting us.

This point is far from original. It has characterized modern thinking about us and the world, from Kant's 'Copernican revolution' to contemporary theory of knowledge. Its special importance here is that it puts our inquiry in its proper perspective: to ask about the formation of new concepts is to ask about the process by which we discover the character of the world.

If we understand concepts as the fund of expectations in terms of which we structure our experience, it becomes clear that concepts and theories cannot be separated. My concept of a lamp is my theory of a lamp, in the sense in which 'theory' means the set of propositions, expectations, insights, that enables me to deal with it. Only in formal systems, again, do we have any luck in distinguishing between concepts and theories. There we can talk about a term, formally limited to a certain intension, and the propositions in which that term appears. In our actual inquiry into the world, however, we can only talk about overlapping theories. Isolated 'concepts', as formally used, are abstracted from theories. The common idea that theories are 'built out of concepts reverses the real process.

Wittgenstein expresses this when he says that concepts are theory-laden. Our idea of 'pawn' carries with it and depends for its sense upon the idea of the game of chess. The concept of'mass' is part and parcel of our concept of Newtonian physics. To ask about the formation of new concepts, again, is to ask about the formation of new theories, or still again, to ask about the formation of new sets of expectations for dealing with the world.

'New concept', like 'concept', is another of those deceptively simple common-sense terms.

In its most general sense a new concept, like any new thing, is what comes up for the first time. For a child the idea of a circus is at some time new. For most adults the ideas of planned obsolescence, the population explosion, escalation, the genetic code, are still relatively new. Learning is interaction with new concepts. Because a new concept is one that comes up for the first time, it is unexpected. It is subject to a special sort of attention and comes to be perceived like a figure against the background of familiar and therefore relatively unnoticed situations.

Concepts are always new with respect to a variety of things. We can no more talk about intrinsic novelty than we can talk about intrinsic parenthood, since concepts may be new in some respects and old in others. It is worth spelling out some of these distinctions in kinds of novelty.

Perhaps most significant is the distinction between a new concept and a new concept of 'this'. Suppose you have an old friend who has bidden from you the fact that he is a Mason. When you hear of this for the first time, your notion of the man changes— but not your notion of Masons. You had a notion of Masons before you knew that he was one of them. Again, a chemist tests a liquid, and finds that it is an organic solvent. He forms a new concept of the liquid, but the notion of organic solvent is an old one for him and does not change in this process. In both cases, what is new is the first identification of a specific thing as an instance of an old concept. The concept itself does not change except in the trivial sense of being found applicable to one more instance.

On the other hand, there are concepts in chemistry—like 'stereo-regular polymer'—which are new for the culture of chemistry as well as for the specific things to which they are applied. When a child first stumbles on the notion of infinity— as the concept of a series 'that you can't come to the end of'—the concept is new for him and not just for the things or numbers with which he is concerned in his discovery of it. New concepts in this sense are my concern in this book.

I have hinted at the distinction between a concept that is new for an individual and one that is new for his culture. The child's notion of infinity was new for him but not for his culture; the chemist's notion of stereo-regular polymers was new for his culture as well—like such ideas of our time as the cold war, atomic fission, and the population explosion. Since concept formation is very much alike in discovery and rediscovery, I will be looking at concepts new for an individual whether they are new for his culture or not.

New concepts grow out of what has gone before and can be seen as changes in the old. But these changes are matters of degree. In some cases the new concept is recognizable as a minor variation of an old one, as in the case of the derivation of 'superjet' from 'jet'. In other cases the new concept's connection with the old may be obscure, as in the case of the emergence of Marx's notion of a classless society or Bohr's idea of a quantum leap.

The ...