![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

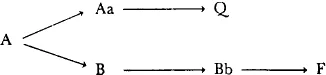

The two earliest printed versions of Othello, the Quarto of 1622 (Q) and the Folio of 1623 (F), were not the very first texts of the play, for a manuscript in Shakespeare’s hand must have preceded them. In this study of ‘the texts of Othello’ I suggest that Shakespeare (like other dramatists of the period) wrote a first draft or ‘foul papers’1 and also a fair copy, and that these two authorial versions were both copied by professional scribes, the scribal transcripts serving as printer’s copy for Q and F. So the ‘texts’ of my title refer not to two but, in the first instance, to six versions of the play, which it will be convenient to designate A (foul papers) and Aa (scribal copy taken from the foul papers), B (authorial fair copy) and Bb (scribal copy), and Q and F. The six texts might then be arranged in a family tree, growing from left to right:

Unfortunately textual relationships can turn out to be almost as complicated as human relationships. As will appear, Qand F are not entirely independent strains, since F shows signs of ‘contamination’ directly from Q, a cross-fertilisation as unwelcome (from the editor’s point of view) as are other kinds of incest.

The six early texts are the most important ones, but they are not the end of the story. I shall have to keep an eye on the Second Quarto (Q2, 1630) and later printed editions – especially Arden 3, the third version of the play to be published in The Arden Shakespeare. Arden 3 follows Arden 1 (edited by H.C. Hart in 1903) and Arden 2 (edited by M.R. Ridley in 1958), and is the ‘only begetter’ of The Texts of ‘Othello’: that is, the two studies of Othello were planned as companion volumes, each self-sufficient and yet each lacking much detailed information found only in the other.

To return to the six early texts: four of the six have perished and cannot be inspected, so it may seem that I propose to build on insecure foundations. To some extent this is true, though not more true than in the case of any other editor of Othello. Every editor has to explain the provenance and transmission of his text or texts, whatever the number of lost intermediate versions. I have a significant advantage over previous editors of the play if, as I would like to think, I have identified the scribe of Bb, a man with quite distinctive scribal habits that can be checked in surviving manuscripts: this identification, if correct, solves dozens of textual problems in Othello and brings not only Bb but also B into sharper focus, which, in turn, throws new light on A and Aa. Four of the six texts may have disappeared, but the editor’s task is far from a hopeless one. On the contrary, what with the new information that follows about the publisher of Q (chapter 3), the scribe of Bb (chapter 6), and about Shakespeare’s often illegible writing (chapter 8), we are in a good position to rub away the film of old theories and to see the textual problems of Othello more clearly. As might be expected, some of these problems are not peculiar to Othello: the argument has to be tested against other Shakespearian texts, and opens up larger issues. In the first place this is a study of the texts of one play, but at the same time the reader should be prepared to reconsider some of the basic assumptions of our textual criticism of Shakespeare.

This, then, is a book that has much in common with J. Dover Wilson’s The Manuscript of Shakespeare’s ‘Hamlet’ and the Problems of its Transmission (Cambridge, 2 vols, 1934), being similarly concerned to track down scribes, compositors, the sources of error, etc., even though in some ways more wide-ranging – for instance, in its archival dimension, and in the use made of the ‘Pavier quartos’ and the Crane manuscripts. Like Dover Wilson’s book, it has a ‘detective’ interest as the evidence accumulates and is gradually fitted together. I can only hope that, though not endowed with Dover Wilson’s skills, I communicate the excitement of such work, and that readers will understand the need to master so much textual detail. The words, after all, are the words of Shakespeare, even if the hands are the hands of Aa or Bb, or of compositors B and E. If it turns out (among other things) that some of Shakespeare’s most sublime poetry has been mislined and consequently misread for centuries (chapter 10), for that reason alone the effort should be worthwhile.

Having introduced my aims and hinted at some conclusions, I have two other introductory duties. First, to describe Q and F, and to outline some of the extraordinary differences of the two texts; and, second, to provide a preliminary survey of recent editorial thinking about these two texts.

The Quarto was entered in the Stationers’ Register on 6 October 1621. ‘Thomas Walkley Entred for his copie vnder the hands of Sir George Buck, and Master Swinhowe warden, The Tragedie of Othello, the moore of Venice … vjd’.2 Q, printed the same title, and added ‘As it hath beene diuerse times acted at the Globe, and at the Black-Friers, by his Maiesties Seruants. Written by William Shakespeare. [Ornament] London, Printed by N.O. for Thomas Walkley, and are to be sold at his shop, at the Eagle and Child, in Brittans Bursse. 1622’. Q collates A2, B–M4, N2, and consists of forty-eight leaves; after an epistle, ‘The Stationer to the Reader’ signed ‘Thomas Walkley’, the text follows on pages numbered 1 to 99.

The other early text of Othello was published in the Folio collection of 1623; placed third from the end, it precedes Antony and Cleopatra and Cymbeline. Like Q it has the title The Tragedie of Othello, the Moore of Venice. It occupies thirty pages, printed in double columns; on the last page, after ‘FINIS’, it gives a list of ‘The Names of the Actors’ (Fig. 4).

According to Charlton Hinman’s Through Line Numbering,3 F – one of Shakespeare’s longest texts – contains 3,685 lines, about 160 lines more than Q. F’s 160 additional lines include more than thirty passages of 1 to 22 lines; amongst F’s most interesting additions we may note Roderigo’s account of Desdemona’s elopement (1.1.119–35), Desdemona’s Willow Song (4.3.29–52, 54–6, 59–62) and Emilia’s speech on marital fidelity (4.3.85–102).

‘Apart from passages in which the texts are divergent’, said W.W. Greg,4 ‘Q has only some five half-lines that are not in F.’ A slight understatement, but it remains true, I think, that ‘the F omissions are trifling and doubtless due to error’.5 In addition, it has been estimated, Q and F diverge in about a thousand readings (hence the need for a more systematic scrutiny of ‘the texts of Othello’ than has appeared to date). The figure depends on how we define divergence; if differences of punctuation are included the figure would be much higher. Whatever their precise number, the many variants of the play pose editorial problems of exceptional complexity, equalled (in the Shakespeare canon) only by Hamlet and King Lear.

Both Q and F were press-corrected, which added yet more variants.6 The press corrections may but need not restore manuscript readings, since proof-readers sometimes examined the first ‘pulls’ or rough proofs without checking the printer’s copy, i.e. sometimes corrected without authority.

More than fifty oaths, printed by Q, were deleted in F or replaced by less offensive words. Editors used to assume that F was purged because of the Act of Abuses, 1606, which prohibited profanity and swearing, but we now know that some scribes omitted profanity for purely ‘literary’ reasons and that not only prompt-books but even private transcripts were purged. On the assumption that the profanity stems from Shakespeare, modern editors revert to Q’s readings. If more QF variants could be shown to point back to a single cause, as with F’s purgation of profanity, the editor’s task would be easier: as will appear, the identification of the scribe of Bb helps us to make some progress.

Both Q and F divide the play into acts and scenes. Q numbers only Acts 2, 4 and 5, and one scene (2.1); F numbers the acts and scenes as in modern editions, except that F’s 2.2 combines two scenes (2.2 and 2.3 in Arden 3). Nevertheless, scene divisions are marked in Q with the usual Exeunt, and in effect Q initiated the divisions adopted by all subsequent texts. Q however, was the first of Shakespeare’s ‘good quartos’ to be divided into acts, and its act divisions (like F’s) may have no authority.

The stage directions in Q and F ‘have a common basis’ (Greg7). Q’s are more complete, and, said Greg, ‘might all have been written by the author’; some give essential information that could not have been inferred from the dialogue. I list some of Q’s more revealing stage directions, adding F’s (if any) in square brackets.8 1.1.80 ‘Brabantio at a window’ [‘Bra.Aboue’, speech prefix]; 157 ‘Enter Barbantio in his night gowne, …’ [‘Enter Brabantio, …’]; 1.3.0 ‘Enter Duke and Senators, set at a Table with lights and Attendants’ [‘Enter Duke, Senators, and Officers’]; 124 ‘Exit two or three’; 170 ‘Enter Desdemona, Iago, and the rest’ [‘… Iago, Attendants’]; 2.1.0 ‘Enter Montanio, Gouernor of Cypres, …’ [‘Enter Montano, …’]; 55 ‘A shot’; 177 ‘Trumpets within’; 196 ‘they kisse’; 2.3.140 ‘Enter Cassio, driuing in Roderigo’ [‘… pursuing Rodorigo’]; 152 ‘they fight’; 153 ‘A bell rung’; 3.3.454 ‘he kneeles’; 465 ‘Iago kneeles’; 4.1.43 ‘He fals downe’ [‘Falls in a Traunce’]; 210 ‘A Trumpet’; 5.1.45 ‘Enter Iago with a light’ [‘Enter Iago’]; 5.2.0 ‘Enter Othello with a light’ [‘Enter Othello, and Desdemona in her bed’]; 17 ‘He kisses her’; 82 ‘he stifles her. / Emillia calls within’ [‘Smothers her./ Emilia at the doore’]; 123 ‘she dies’; 195 ‘Oth. fals on the bed’; 232 ‘The Moore runnes at Iago. Iago kils his wife’; 249 ‘she dies’; 279 ‘… Cassio in a Chaire’ [‘Cassio’]; 354 ‘He stabs himselfe’; 357 ‘He dies’[‘Dyes’].

As this selection shows, Q supplies more detail than F, and F lacks many directions that one would expect from a prompt-book: sound effects, stage movement and lighting are all neglected. On the other hand, Q is sometimes vague (‘two or three’, ‘and the rest’) and omits some essential equipment (Desdemona’s bed) – quite like other Shakespearian texts that supposedly derive from foul papers. Some of Q’s unusual phrasing can be matched in the stage directions in other plays (cf. p. 161).

Next, a quick survey of editorial thinking about the provenance and transmission of Q and F. Opinions have differed, and my summary is meant to highlight the differences, without pretending that this is a survey of all the possibilities.

(1) E.K. Chambers, 1930. ‘Q and F are both good and fairly well-printed texts; and they clearly rest substantially upon the same original’. F was ‘printed from the original and Q from a not very faithful transcript, without a few passages cut in representation. It must have been an early transcript, in view of the profanities. Whether it was made for stage purposes or for a private collector one can hardly say.… The Q stage directions may well be the author’s, but the transcriber might have added some marginal notes for action, not in F.’

(2) Alice Walker, 1952, 1953. Q ‘was a memorially contaminated text, printed from a manuscript for which a book-keeper was possibly responsible and based on the play as acted’; F ‘was printed from a copy of the quarto which had been corrected by collation with a more authoritative manuscript.’

(3) W.W. Greg, 1955. ‘Q appears to have been printed from a transcript, perhaps of the foul papers … The date of the transcript is unlikely to have been earlier than 1620’. Greg agreed, following Miss Walker, that F was printed from a copy of Q collated with a manuscript. The manuscript, he thought, was probably the prompt-book, prepared by a scribe. Hence ‘we get a picture of two different scribes struggling with, and at times variously interpreting, much and carelessly altered foul papers – perhaps even of alterations made by the author or with his authority after his draft had been officially copied’.

(4) Fredson Bowers, 1964. ‘Dr. Walker’s case (though correct) is not nearly so copious or rigorous in its evidence as to make for an acceptable demonstration’. Concluded that ‘once the necessary compositor studies have been made, the rigorous application of this evidence … may hopefully lead to a final determination of disputed printed versus manuscript copy in the Folio’.

(5) J.K. Walton, 1971. Argued that F Othello was not printed from corrected Q(as Miss Walker had claimed), but from a manuscript.

(6) Stanley Wells, 1987.9 ‘Q represents a scribal copy of foul papers. F represents a scribal copy of Shakespeare’s own revised manuscript of the play’.

‘There must have existed a transcript by Shakespeare himself

Here we may pause to pick out some of the more interesting differences. Chambers, Greg, etc., consider Q a good text; Miss Walker thinks it contains ‘a solid core of variant readings only explicable as memorial perversions.’ Chambers dates the Q transcript ‘early’ (i.e. before 1606), and Greg iate’, not earlier than 1620. Chambers, Walker and Greg assume that there was only one authorial text, Wells that there were two. The F manuscript puzzles some of the commentators, including Greg who confesses that he has ‘slipped into thinking of the manuscript that lies at the back of F as the prompt-book’, but notes some evidence to the contrary. Wells observes that F’s stage directions ‘are not strongly theatrical …. Particularly striking is the total absence from F of music cues’; unusual spelling and punctuation suggest that ‘another hand intervened’ between Shakespeare’s transcript and F’s printed version.

One other difference deserves immediate attention. J.K. Walton’s The Quarto Copy for the First Folio of Shakespeare (1971) received mostly neutral or unfavourable reviews,10 yet his rebuttal of Miss Walker’s theory gradually won support.

(7) Rich...