eBook - ePub

Movement in Cities

Spatial Perspectives On Urban Transport And Travel

- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Movement in Cities describes and analyses urban travel in terms of purpose, distance and frequency of journeys and modes and routes used, concentrating mainly on British towns with many references to the United States and Australia.

The authors elucidate the all-important interrelations between location of activities and the patterns of transport supply and use within towns. The issues they raise are of pressing practical and intellectual importance.

This book was first published in 1980.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Movement in Cities by P.W. Daniels,A.M. Warnes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The transport revolution

and urban growth

Person and vehicle movements in today's cities are as much guided by the events of the past as they are shaped by the requirements of the present. The process of evolution and its effects on the growth of cities was slow, but the momentum increased quickly during the eighteenth century as a result of the stimulation provided by the industrial revolution. More efficient methods of moving larger quantities of raw materials and goods were needed and increased industrial and commercial activity generated growing demands for people to travel within and between cities. Migration from rural areas to the cities also encouraged more advanced transport facilities and services beginning with the stage coaches of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Probably the most significant feature in the evolution of transport during this period was that it became possible to travel increased distances without consuming more time. This was crucial in the context of urban development because it allowed the residences and workplaces of urban dwellers to be separated to an increasingly significant degree and changed the traditional ‘compact’ city to a more dispersed form. Cities which were proving particularly attractive to industrial entrepreneurs and to rural migrants seeking work could begin to handle these demands more effectively as well as to sustain the effectiveness of their urban functions. In addition, new methods of movement conferred different accessibility advantages on intra-urban locations and encouraged functional segregation of land uses and the appearance of some new uses, such as higher-order retail functions. This would not have been possible without the liberalizing influence of urban transport technology in the sense that it promoted outward expansion of cities, with residential development leading the way, while at the same time sustaining the accessibility advantages of the centre.

The golden era of urban transport evolution was undoubtedly the nineteenth century. The pace of transport development was more rapid than at any other time and its consequences were not confined to changes in city form and growth but extended to increasing the volume of movement, its composition, and the purposes of urban trip-making. These structural changes in urban travel have continued to take place and have presented cities with a wide range of transport-related problems with origins in the events of a century and more ago. Some of the more important nineteenth-century developments are therefore worthy of closer examination as part of the explanation for the existing characteristics of movement in cities which occupy such a prominent place in this book.

Urban transport and travel before 1830

Up to the beginning of the nineteenth century the structure of cities was in part dependent upon the distances which residents were prepared to cover on foot in order to conduct their work, recreation, social activities or business transactions. The planning and arrangement of cities was undertaken in a way which would minimize the need for internal transport, both in terms of the number of trips necessary and the length of these trips (Schaeffer and Sclar, 1975, pp. 8–17). City space was therefore characterized by extremely high densities with narrow streets, buildings built as high as contemporary construction techniques would allow and little or no wasted land except where ground conditions made building impossible - housing even spread across the bridges over the Thames in London. Such ‘foot cities’ lacked the distinctive social and functional segregation of land uses which are well-developed in modern cities (see also Boal, 1970, pp. 73–80). Buildings served not only as family homes but as workshops for the family so that the tanners, bakers, candlestick-makers or moneylenders operated from the same premises as their family residence. In addition, they often provided accommodation on the same premises for apprentices, housekeepers, relatives and others needed to keep the business or the household in successful operation. With employers and employees resident on the same site the journey to work requirement was much more limited than today and, depending on the self-sufficiency and the size of individual households, most of the trips generated were in connection with businesses or shopping. While congestion was not unknown in such towns and cities, the street system was perfectly adequate until technological changes led to an erosion of the household organization as economies of scale encouraged larger production and business units and, eventually, the separation of homes from workplaces. This could not have taken place without the aid of developments in transport technology which took place during the nineteenth century. Although it is difficult to prove whether increasing separation of homes from workplaces was the main stimulus for transport development or vice versa; given that most entrepreneurs could not provide a transport service ahead of demand it seems reasonable to suggest that changes in urban structure preceded transport improvements. These substituted the dependence on foot transport with vehicles which permitted, in relative terms, rapid exchange of goods and services as well as larger quantities than could

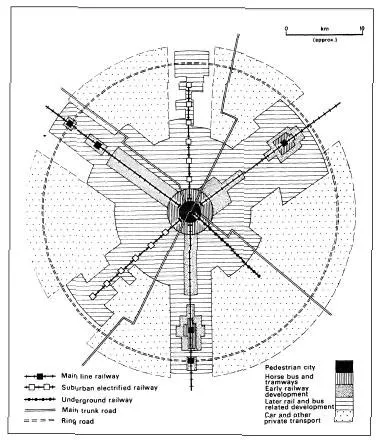

Figure 1.1 Schematic relationship between urban form and transport

be moved by one man or by pack animals. Toot cities’ could rarely expand beyond a population of 50,000. The nineteenth century transport revolution allowed this to be increased many times over without apparently impairing the efficiency of the city. The link between transport and urban development was firmly forged during the century and the ‘foot city’ was soon replaced by the ‘tracked city’ and, during the twentieth century, the ‘rubber’ or ‘highway’ city (Schaeffer and Sclar, 1975, pp. 18–60).

Therefore, major changes in transport technology which began to emerge during the first quarter of the nineteenth century had a major influence on the growth of cities, the organization of their internal structure, and the supply, demand, efficiency, speed and opportunities for movement within them. There can be little doubt that cities would never have increased in size and complexity without the stimulus and guidance provided by a transport network which helps to smooth out the differences between locations in terms of locational advantage/disadvantage as well as reducing the time/distance between sets of points in an area of urban growth (figure 1.1). As Mumford has observed the ‘purpose of transportation is to bring people or goods to places where they are needed’ in a way which will ‘widen the possibility of choice without making it necessary to travel. A good transportation system minimizes unnecessary transportation; and in any event it offers a change of speed and mode to fit a diversity of human purpose’ (Mumford, 1964, p. 178). This is precisely what took place in nineteenth-century cities in Britain. Marked improvements in socioeconomic indices such as real income, security of employment, occupational status and shorter working hours also occurred in parallel with, if not partially as a consequence of, transport improvements as the century progressed and this helped to swell the demand for movements of various kinds. Indeed, the way in which our cities and towns have grown and organized themselves internally in response to transport changes through time has helped to mould some of the transport problems which they now face in an attempt to match the demand for movement and urban development processes. Hence, it has been suggested that the ‘modern metropolis in both its good and bad features is peculiarly a product of transportation technology’ (Rae, 1968).

Almost all the transport innovations which led to increased mobility of urban residents in the nineteenth century were based on public transport, although many of the improvements in carriage-building technology were devised by private companies such as Pickfords who were involved in the rapidly expanding carrying trades in the major cities. Personal private transport was mainly a privilege enjoyed by the very wealthy who could afford to purchase and operate horse-drawn carriages. Intra-city public transport was mainly a product of the period after 1830 - prior to this time public transport had been almost exclusively inter-city. The long-distance stagecoach dominated these long-distance routes, to be followed and eventually replaced by the railways during the first half of the century (Dickinson, 1959). The well-developed canal network between settlements was the main method for moving goods and raw materials, while within cities movement of goods was highly inefficient, depending mainly on horses and some horsedrawn carts. Some cities, such as Birmingham, did have quite well-developed urban canal systems, but this was exceptional and, in general, there was little scope for enhanced industrial and commercial location in towns and cities until superior transport networks were introduced. The canals were insignificant for person-movements but cities with navigable rivers, such as London, Liverpool and Glasgow, did have ferry services in operation at the end of the eighteenth century. Apart from their contribution to movement into and within these cities, the ferries helped to open up new areas for urban development, such as Birkenhead across the Mersey from Liverpool, which had previously been inaccessible.

Before the development of public transport most movements in British cities were made on foot, whether for the journey to work, day-to-day business affairs or social activities. This imposed sharp limitations on the outward spread of most urban areas to a maximum of three miles, or approximately one hour's walking distance, and in most cases much less. For the vast majority of the population workplaces and residences were in close proximity with most people working in their immediate locality (see, for example, Warnes, 1970). Functional separation of urban activities was far less obvious than today because movement between activities was time-consuming, and only really essential trips, such as the journey to work, were made. Opportunities for making other trips were restricted by the length of the working day — ten hours and more. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, towns and cities were, therefore, very compact and while the patterns of movement within them may well have been complex, trip purposes were restricted and inflexible.

Cities remained compact until the railways became more interested in providing short-distance services. But during the interim there were a number of other important developments in urban public transport. Short-stage coaches were the first to attempt to operate within urban areas, particularly the larger centres such as London and Birmingham, either providing totally independent services or as feeders to the railways. This traffic had reached considerable proportions in the London area by the early 1820s. Some 600 short-stages a day, making 1,800 journeys, left the City and West End to destinations in the suburbs and outlying villages to the south and north-east of the Thames (Barker and Robbins, 1963, pp. 4–5). Each coach carried four to six persons inside as well as some outside passengers, but journeys were costly; 1s. 6d.—2s. single to the City or West End from Paddington. Only the wealthier classes could afford to use them.

The rapid evolution of road transport techniques

But the short-stage coaches were comparatively short-lived and quickly usurped by the larger, more comfortable horse omnibus which came into popular use in London in 1829 on a service from Paddington to the Bank (Dyos and Aldcroft, 1971, pp. 219–20). The journey time was scheduled as one hour but the five-mile journey sometimes only took forty minutes (Barker and Robbins, 1963, p. 22). The capacity of the early omnibuses was twelve persons but in later versions some were able to carry twice this number. The original fare was 6d. per trip but later, when competition became more severe, charges fell to a standard fare of 1d. for each journey. This made the omnibuses more accessible to a wider cross-section of the population. Although the early services were along set routes, there were no official picking-up and dropping-off points — these did not become legal in London until 1832. But by the mid-nineteenth century the horse omnibus was a more important urban carrier than the railways and by 1860 the London General Omnibus Company, which alone owned some 600 vehicles of the 850 on the streets at the time, was carrying 40 million passengers a year on sixty-three distinct services in and around London (Dyos and Aldcroft, 1971, p. 220; Savage, 1959, pp. 87–9). The diffusion of the horse omnibus to provincial cities occurred some years later - to Leeds in 1839, Birmingham in 1860, and Bradford in 1870 - but the evolution of the service network, fare structures, and the contribution to increased person movement and, to a more limited degree, goods movement, was much the same. Horse omnibuses were expensive to run, however, and therefore steam carriages were tried in London between 1821 and 1840 but mechanical problems rendered a promising future uncertain and they only offered short-lived competition to the omnibuses.

By the end of the 1860s the demand for horse omnibus journeys was growing steadily each year and signs of peaking in person and vehicle movements were already beginning to appear as the clerks and artisans able to afford the fares for suburban journeys lived in increasing numbers outside the overcrowded city centres. Much of the congestion was caused by the limited capacity of the horse omnibuses, which meant that large numbers were required to satisfy demand. This congestion was exaggerated by the limited range of the omnibus and, in cities which were still essentially compact, journey times were particularly slow in the central areas. A more rapid method of transport with a larger carrying capacity would soon begin to test the dominance of the horse bus. In their heyday, fares on the horse omnibuses had come down to less than 1d. per mile in the larger cities, such as Sheffield, Leeds and London, and the average speed, including stops, of town services was five miles per hour (Savage, 1959, p. 89).

It has already been suggested that the railways were slow to emerge as serious competitiors to the horse omnibuses. This allowed horse trams, introduced commercially in London and Birmingham in the late 1860s, to share fully in the ever-growing demand for public transport during the second half of the century. The main advantages of the horse trams were their greater carrying capacity (almost double that of the horse bus), greater efficiency because there was less friction encountered by the horses pulling the trams, the ease with which passengers could climb on and off, and the ride which was smoother and safer than the horse omnibuses. The first urban tramway in Britain was constructed in Birkenhead in 1860 and ran between Woodside and Birkenhead Park, but it was not a great success because of a number of accidents which led to adverse publicity and great public uncertainty about the safety of the trams (Savage, 1959, pp. 89–90). The same entrepreneur, G. F. Train, opened two short experimental lines in central and inner London in 1861, but again with comparatively little success, partly because he insisted on using elevated tracks which naturally interfered with movement of other traffic on the roads. It was another ten years before tramways became an accepted form of transport to and between the suburban areas of our major cities such as Liverpool, Hull, Glasgow and London.

There was much initial hostility from residents in affected streets, from some local authorities and government departments, but a tramway finally became fully operational in Liverpool in 1868, and in London in 1870. Expansion of networks was slow, however, mainly because of restrictive legislation and the tight control on the operation of tramway undertakings which were exclusively private companies. Initially, therefore, the horse tramways had a very limited route mileage so that they in no way totally replaced the horse bus which frequently used similar routes up to five miles from the centre of towns. In 1878 there were only 237 miles of tramway in the whole country but by the turn of the century this had increased to 1,000 miles and by 1911 to 2,500 miles (Savage, 1959, p. 90). Prior to 1904 most of the trams were horse-drawn and they suffered the same basic disadvantages as the horse omnibuses and did not greatly extend the length of urban trips. There were some steam trams operating in the Black Country, the North of England and Scotland, but substantial improvements in journey times and the length of networks only became possible following the introduction of electric traction. Leeds began to install electric trams in 1891 but they did not enter general service throughout the country until the early years of this century. By 1914 there were some 12,000 electric trams in operation, mainly in urban areas, and they carried some 3,300 million passengers. Municipalization of tramway systems also began to take place at the end of the nineteenth century and this permitted the introduction of cheaper fares which then allowed the working classes to live further from their places of work than before (for a full discussion, see Dickinson and Langley, 1973).

Both the horse omnibus and the tram benefited from the general increase in the propensity of urban residents to travel. This was encouraged by the lower fares which resulted from the intense competition between the two modes along the major arterials. The tramways could achieve less comprehensive coverage of outer areas than the omnibuses because they were tied to tracks which clearly did not allow easy introduction of new routes or the operation of experimental services in untapped areas of the suburbs. They were also almost totally excluded from the central area of London, which remained the domain of cabs and horse omnibuses almost until the end of the century. Elsewhere, such as Manchester, this was not the case and virtually all the city's tramway routes converged on Market Street and made the area an ideal location for the growth of commerce and entertainment which was dependent on substantial patronage.

The urban transport role of railways

Throughout this period the railways, as a mode of travel within urban areas, were becoming better-established but only provided very limited coverage of the existing areas of urban development or potential areas for urban expansion. The railways certainly handled the longer-distance suburban journeys of six miles or more, leaving the omnibuses and trams to handle the shorter-distance traffic, but the opportunities for short-distance rail passenger work in London, for example, were not demonstrated until 1836 and it was another forty years before railways became extensively used for urban trips. It should be remembered, of course, that the scale and extent of British cities was very restricted until late in the nineteenth century - the continuous built-up area of Manchester for example, extended no more than two miles from the Market Place at mid-century. Most of the railway construction activity of the last quarter of the nineteenth century was in fact confined to extensions into the suburbs and the immediate hinterland of the larger cities. The road-based modes of travel often provided feeder services to those stations which did exist within ten to fifteen miles of the cities, but, in general, intra-urban movement remained confined to a zone within four to six miles’ radius of the city centre. The rail services which were used, for the journey to work in particular, depended upon patronage by the wealthy classes - return fares of one shilling per day were an impossibility for the majority of urban residents who earned £ 1 per week or less.

But there can be no doubt that the railways were the key to much more rapid outward expansion of Victorian cities (see, for example, Kellett, 1969; Perkin, 1970). Clark (1957–8, p. 248) has suggested that they were the ‘implement which really chiselled apart the compact Victorian city'. In many cities, however, the railway companies did not possess termini near enough to the centre to provide the kind of access to centres of employment which the trams and omnibuses provided. Neither could they utilize existing facilities for their routes and services - they had to crave routes through existing built-up areas and they eventually came to own eight to ten per cent of central land in cities as well as indirectly influencing the functions of twenty per cent of all urban land (Kellett, 1969, p. 2). Because of their preoccupation with inter-city services the railways had been largely concerned with locating city termini where property values were lowest and this was usually at the edge of the built-up area. Quite commonly these early terminals were subsequently converted to goods depots as the railway companies undertook extremely expensive extensions into and through the central area to serve larger-capacity termini. The goods depots at Oldham Street and Liverpool Street in Manchester, at Edge Hill in Liverpool and at Bricklayers Arms in south-east London are all examples. The London Bridge terminus of London's first suburban railway, the London and Greenwich, was fortunately within easy walking distance of the City and the railway carried more than 650,000 passengers on its frequent trains during the first fifteen months of its existence. The trains travelled at fifteen-minute intervals and when the line was fully extended to Greenwich in 1838 horse omnibuses from Blackheath, Lewisham and Woolwich were scheduled so that they met every train. This had clear implica...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- 1 The transport revolution and urban growth

- 2 The activities of urban populations and their relationship to urban movement

- 3 The aspatial characteristics of movement

- 4 Goods movements within towns

- 5 Spatial patterns of urban movement: the organizing principles

- 6 Spatial patterns of urban movement: empirical evidence

- 7 Analysis and prediction of travel patterns

- 8 The development of legislation concerning urban transport policies and planning

- 9 Management of urban travel demands

- 10 Some topical issues in urban transport decision making

- 11 The geographical perspective on urban movement

- Bibliography

- Index