![]()

INTRODUCTION

There are many indications that the Japanese are a racial amalgam, the major constituents arriving both from the west, over the northern mainland of Asia, and from the south, by way either of the Pacific islands or the southeastern fringes of China. The Japanese language itself affords a good example of this diversity of origin. It has certain structural affinities with Korean and with other members of the Ural-Altaic group. One influence of such links is to be found in the phenomenon of vowel harmony—the appearance of only one of the vowels within a given word, even to the point of variation in a suffix vowel to retain symmetry with that of the word to which it is attached. Another pointer to the Ural-Altaic kinship of Japanese lies in the nature of its number words; the root of the word for ‘five’, as in Mongolian and Manchurian, is related to that for ‘to close’, the roots of the word for ‘ten’ and of ‘open’ are identical—and as he counts on the fingers of one hand, the Japanese closes down from one to five, so that the fist is clenched on five, then he opens up one finger each for six to ten, ending with an open and extended palm.

Yet, although these and other structural parallels occur, there has been little vocabulary borrowing from this linguistic group. On the other hand, the peoples of the Pacific, the second main component of the Japanese racial make-up, while they have worked little or no influence on the structural features of the language, have yet given it many of their words. Vocabulary identities exist between Japanese and, among others, Formosan, Annamese, Tagalog, Malay and the language of Munda. These, of themselves and unsupported by structural or grammatical parallels, prove little more than that the Japanese have long been good borrowers; it was an old-established trait that led them in the sixteenth century to adopt from the Portuguese pan and kasuteira for bread and castella—a kind of sponge-cake—and in the twentieth, to incorporate a host of words from all over Europe and the Americas. Nor does the Japanese word-hunter simply borrow; he distorts—to suit his physical and vocal limitations, a weak lower lip for example—he abbreviates and cross-breeds with his loan-words to father linguistic mongrels of the kind of aru-saro—which stands for ‘arbeit salon’, the poor man's night club where the needy student arbeits to provide her tuition fees.

There is other evidence for the South Sea contribution to the Japanese racial composition. Many of the books of the ‘Spirit of the Japanese Nation’ type, written in English around the turn of the century by Japanese who had visited or received an education from the West, point to two basic physical patterns; the one, the northern stream, has the noble face, the lighter skin and the high angular nose of the so-called ‘princely’ Mongol stock, the other has the dark pigment, the flattened nose and the broad lips of the man born near the equator. And where, in the linguistic field, the northerner appears to have triumphed, in many cultural aspects it is the influence of the southerner that is still the stronger. The Japanese architect, for example, except of course for the designer of the twentieth century department store and office block, has never quite come to terms with the chill of the snow and the winter winds of this new northern home, although his planning is ideally matched to the sticky heat of the Japanese summer. And though, like the Englishman, the Japanese will often use a comment on the weather to start up a conversation, you hear the exclamation ‘Isn't it cold?’ in winter far more often than the Englishman's heatwave greeting, ‘Isn't it hot?’

Again, in matters that are the subject of this inquiry, the concept of the deity, origin myths, folk practices and so on, there are frequent approximations between the Japanese and the Polynesian. This is not to claim racial affinity (as the Japanese have often done) on the score merely of such meagre analogous occurrence or development; the student of cultural history—for want of a better term, though the Japanese fondness for it renders it eminently appropriate here—is confronted by too many such parallels, occurring often almost simultaneously at opposite ends of the world, to conclude other than that there is and has been a deal of haphazard and unrelated convergence.

The culture and manners of this racial amalgam are often the outgrowth of a wide-ranging eclecticism. Yet the products of the borrowing to which this eclecticism has led are only rarely allowed to escape the thoughtful and modifying attention of the borrower. Until modern times it was the Chinese cultural bank (and its Korean branches) that was almost always the chief creditor, and only rarely in Japan's history, under an intensely nationalistic and isolationist regime, has the charge of un-Japanese activities been levelled against such as imprudently displayed zeal for or erudition in matters Chinese. For the rest, offering precious little in return (the list of her cultural exports to China contains cormorant fishing, the rickshaw and not much more) Japan has usually acted as an avid assimilator of just about everything that found its way either up to China from India and thence to Japan, or direct from China or—and sometimes already in a stamp other than the original—from China by way of Korea. Japan's islands, lying off the east coast of the Asiatic mainland, were the final staging point in the eastward or north-eastern movement of cultural development, in much the same way as England, off the coast of Europe in the direction of the main flow of the Mediterranean cradle cultures, often constituted the final resting point in the journey of once new and exciting discoveries. Thus Japan became, in many aspects, the antique shop of the Orient, finding room for and obliged to accept—as often happens with the antique dealer—much that was already outmoded or quite inappropriate to its new surroundings.

Yet it was just this eagerness to adopt anything and everything on offer that made of Japan the treasure-house of the Orient; and the hoard was enriched in no small degree by the almost museum-type mentality of the Japanese, a trait still very apparent today. I have lived for two years in a newly-built Japanese house and never once sat on a settee stripped of its dust covers in my ‘western style’ room (complete with mantelpiece but lacking chimney-stack), never once been allowed to pollute with my foreigner's gaze the exquisite (or so I was assured by my landlord) black lacquer lining the alcove in the first-floor Japanese room. There are many priceless relics in Japan's Pan-Oriental treasure vaults; only there can you hear today a performance of gagaku—‘elegant music’—which derives very closely from and has preserved all the elements of the music of the T'ang Court; and there is a number of Confucian temples in provincial cities as well as in Tokyo where the ritual of the service is not very different from that detailed in Chinese records of the Ming period.

But let it not be imagined that a knowledge, however broad it be, of things Chinese offers of itself free and automatic entry to this Japanese repository. There are many hindrances to such inter-availability of knowledge. First and foremost, for example, there is the language bar. Agreed, Japanese and Chinese characters are identical, for Japan borrowed to enable, in the first place, the keeping of records. There was no previous system of writing in Japan— there cannot have been, for any earlier or indigenous method must have been better suited to its purpose, as anyone will tell you who has been obliged to struggle with the distortions and the makeshift devices to which the Japanese have been obliged to resort to render this alien vehicle in any way roadworthy. Chinese and Japanese may be written in identical characters, but here all resemblance ceases; linguistic structure, syntax, grammar, division by parts of speech, conjugational aids and so on, all are radically different. The average Chinese university graduate will barely make sense of a passage of Japanese, and the Japanese scholar today, robbed since the war of his ‘O’ Level grammar school Chinese, lacks many of the keys that fit the door to his ancestral inheritance in much the same way that the Latin-less Oxford matriculant is allegedly bereft of the capacity to develop into the compleat gentleman.

It has been the fashion in Japan and China, as well as in the West, to pay little serious regard to, if not openly to deride, this so-called pale reflection of the Chinese original that is to be had in Japan. Ueno Museum in Tokyo has three vast galleries of bronze mirrors; the first is Chinese, the second displays Korean products; and that is where the average museum-goer stops and retraces his steps. My guide halted and hesitated at the threshold of the third gallery: ‘The rest were “made in Japan”,’ he explained and, with a deprecatory shrug of the shoulders when confronted by this distasteful and inferior home-produce, he was for whisking me off to Chinese pots until, forced to turn and enter, he grudgingly admitted that Japan-made mirrors were not so shoddy after all.

In spite of Japan's intense pride in the uniqueness of her civilization (the use of the word koku—‘ational’, ‘of our glorious nation’—as a prefix to terms like ‘studies’, ‘history’ and ‘language’ testifies to this pride) until about the start of this century the best of her linguists, historians and so on have almost always been channelled into the paddy of Chinese studies. It is only with the advent of and the accordance of recognition to scholars in home fields of the calibre of Yanagida Kunio and Origuchi Nobuo (and, more recently, as a result of the gradual growth in inaccessibility of the Asiatic mainland) that there has arisen a group of disciplined schools of Japanese studying Japan. In such circumstances, the old prejudices die hard. If some aspect of Japanese culture bears the external marks of Buddhist, say, or Chinese origin or influence, in many cases that is held to be the end of the matter; research is jettisoned, scrutiny withheld, the Buddhist or Chinese prototype is described in detail and its Japanese imitation briefly analysed in relation to the supposed original. This is a feature, for example, of many of the loose and inadequate discussions by Japanese of the ceremonies of Bon, centred round the fifteenth of the seventh month. An arguable Chinese parallel exists, and it is snapped up forthwith as the genuine prototype. Then, the picture is rounded off by citation of a series of records and directives relating to the Japanese Court. Little place is given to a comparative analysis of the rituals of Bon and the ‘Little New Year’; the latter is celebrated with its central ceremonies

falling on the fifteenth of the first month and the two thus divide the year into half, proving to be, in fact, the main events of many in the Japanese festival year that occur on the fifteenth day, that of the full moon by the old lunar calendar.

The same is true of many studies by Japanese of the element of the race or contest to be found in a number of ritual practices. The Chinese of the south fought out races in long boats equipped with many paddles; so did, and do, the Japanese, particularly those of Kyūshū whose western seaboard is more close to China than any other stretch of Japan's long coastline. Ergo, boat races and any other ceremonies in the nature of a contest are best and most adequately interpreted as direct imitations of the Chinese practice. But look more closely and you find the contest (between fires, boats; a tug of war and so on) in the mountain farming village as well as on the western shores of Kyūshū; you find it more particularly at Bon and at New Year—the two great dividing points in the year when the farmer thinks ahead and wonders how his crops will fare in the period to come—and the contest is, in part, a mode of divination, its outcome an indication of the spirits' will and plan.

It is clear then that for a competent understanding of many of Japan's folk customs, however much they may appear superficially to be a valuable living replica of a Chinese prototype no longer practised or, if still in existence, unrecognizably distorted, one must work down below the Chinese veneer to an indigenous canvas. The distinction between Shintō and Buddhism may often serve as a rudimentary criterion to distil the indigenous from the foreign, for, although the two great religions of Japan quickly merged and, during a thousand years of not unfriendly inter-borrowing, created a ‘Dual Shintō’ which owed much to Buddhism, yet from the seventeenth century onwards there was in certain orthodox yet vigorous Shintō priestly circles a lively attempt to rid the indigenous faith of its alien trappings. However, while many of the folk practices described later do, in fact, come under the protection of Shintō interpreted in its widest sense, this demarcation based on Shintō and Buddhism is, at best, a rough one. The Japanese farmer, if made to stop and think, would no doubt describe the Bon ceremonies of his village as Buddhist; he would most certainly also attribute to Buddhism most of his actions as a participant in funeral ritual: but, as we shall see, there are numerous aspects of either of these which are not Buddhist in origin.

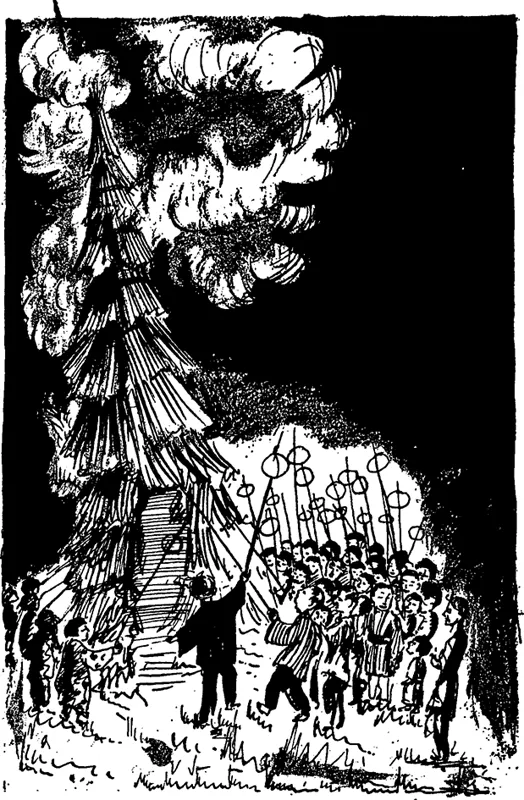

Demon-driving fires are lit on the night of the full moon in the first and seventh months

Again, by and large, Buddhism is of greater account to the individual and Shintō of greater significance to the social group, the mountain hamlet or the small urban collocation. Since most of the folk practices I shall examine are those of the group, we shall be dealing more with ceremonies ascribed to Shintō and practised by Shintō officials or at Shintō foundations.

But now we should pause to define terms. Shintō means, literally, the ‘Way of the Spirits’. But the connotation of this ‘Way of the Spirits’ varies drastically with its context. Tied to the coat-tails of nationalistic fervour, as in the 'thirties and early ‘forties, Shintō's cosmological doctrines became, for many, infallible evidence not only for the divinity and primacy of the Emperor through his direct descent from the Sun Goddess, but also for the unique and invincible qualities of his subjects in virtue of their relationship, as his children, to the Emperor. A national religion, founded not on a canon but on conveniently handy eighth century historical documents (which contained a generous admixture of early myths and primitive cosmological notions) became the foundation of political theory and dogma; the Emperor's position, thus bolstered, was to be subject not even to the analysis of the political theorist, much less to the criticism of any daring opposition spokesman. As such, Shintō became one of the principal targets for suppression and reform during the years of the American occupation. But, through their aversion to precise definition, and their failure—even greater than that of most cultures—to prescribe with any clarity the scope of the terms they use, the Japanese also applied the term Shintō to, or subsumed under the broad wing of the words ‘Shintō ceremony’, a host of folk and traditional practices many of which, not unnaturally in localities where the Shintō shrine was the main or even the only focus of community life, became attached to or were celebrated at such a shrine. The parade of twenty tall floats through the main streets of Kyōto on July 17th is under the patronage of the Gion Shrine, for it was the head priest there who, over a thousand years ago, led the first procession in an attempt to rid the capital of a raging epidemic. Gion Festival is now little other than a traditional holiday parade. Yet, participation in this parade, classified as a Shintō ritual in that it is celebrated from a Shintō Shrine, was condemned as nationalistic and reactionary and was banned for several years at the end of the war, much to the bewilderment of Gion's parishioners. For, when they took part in their great festival of the year, they believed not that they were lending themselves to some warlike activity but that they did merely ‘what comes naturally’. Many of the ‘spirits’ of the ‘Way of the Spirits’ are those of ancestors. So Shintō is often a synonym for ‘doing as our forefathers did’; so ‘acting in true Japanese fashion’, so ‘acting naturally’. Hence the definition of Shintō by an accomplished expert in both Shintō and Buddhism (Jiun, in the eighteenth century), as ‘this pure Japanese naturalness, this spontaneity’.

In the years before contact with B...